In the rock art of the American west and southwest there are frequent images of birds, and one commonly recognized is the turkey.

“Mountain turkeys are a subspecies

of the wild turkey, the race merriami, which is confined to the southwest.

These birds are not the same as our domestic turkeys, though they are wild

relatives which look much like the bronze variety. A domestic gobbler has an

overhung breast, thicker legs, and exaggerated wattles and dewlap; it is inclined

to be overweight and sluggish. The Mountain or Merriam’s turkey, is trim and

muscular, allowing it to travel with great speed and even to soar or plane a

bit – abilities consistent with its chosen habitat, which is the yellow pine

belt of 6,000 to 10,000 feet in elevation.

Their range was from southern Colorado through suitable mountain ranges in New Mexico to near the Mexican border, then through the southern mountains of Arizona, the White mountains and San Francisco peaks.” (Tyler 1991:71-72) Their range has been expanding in recent years. This writer has seen wild turkeys in the Denver suburbs within the last year.

Tyler wrote about Pueblo Indians and turkeys in 1991. “Indian hunting pressure has never been a negative factor, because the Pueblos are at most only casual hunters of game birds. The feathers were and are the desirable part of this bird, and several students have argued that the Pueblos never ate turkeys, keeping them only for their ceremonial values.” (pp. 72-3) There are, however, ethnographic reports that imply, and even record, the eating of turkeys. Evidence such as large quantities of turkey bone, and even scorched turkey bone, would seem to imply preparation as food. That said, the turkey’s impressive feathers would also be a very important motive to hunt them.

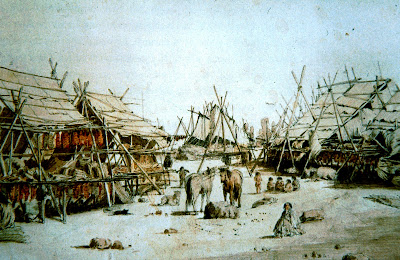

Turkeys and a sheep at First Mesa, Hopi Pueblo original photograph by Kate Cory, 1905–1912. Courtesy of the Museum of Northern Arizona (MS-208-75.929)

According to Conrad (2021:1-2). “In the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest (SW/NW), the last several decades of archaeological research indicate that Ancestral Pueblo peoples engaged in a complex relationship with turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo spp). – These turkeys were often fed domesticated maize (Zea mays), allowed to free-range and exploit non-maize plants and other resources, or a combination of both. – Domestication and subsequent husbandry of turkeys likely occurred for a variety of purposes, but current data suggest that exploitation of eggs for food and paint creation; feather gathering and collection for use in ceremonial activities and blanket production; use of bones for flutes, whistles, ornaments, and a variety of tools; and subsistence all played important roles. Based on the altruistic relationship often identified between humans and turkeys through the presence of broken and healed turkey bones in Ancestral Pueblo habitation sites, the abundance and diversity of turkey/bird iconographic imaery in rock art and ceramics, and the presence of intentional turkey burials, it is clear that these birds held a special role in past Native American society.” (Conrad 2021:1-2).

Conrad’s suggestion that turkey eggs were used in creating paint suggests that they used the paint formulation of egg tempera. In egg tempera the yolk of an egg is used as the binder in the formulation of the paint. I have, however, found no other references to this possible use of turkey eggs as egg tempura by Ancestral Puebloan peoples.

While there are many images of birds in western American rock art, most of them cannot be identified as turkeys. On the designation of turkey images in rock art, for the purposes of this article, I am relying on a few factors. First is I am choosing pictures of reasonably fat birds, usually pictured as standing on the ground – not in flight. According to Robins and Hays-Gilpin (2000:245) turkeys are earth-bound birds, associated with the earth in Pueblo thought, as opposed to sky associated raptors. Another factor is anatomical details sometimes pictured such as the snood, the wattle, and the tassel found on turkeys. I accept that not all observers would agree on each and every image I am selecting (as I do not always agree with such designations by others), but I am confident that most of them will be found agreeable. Another trait often considered to identify of turkey in rock art is a spread tail as in a displaying male bird.

Schaafsma (1980) considers birds including turkeys to be elements of importance in her Chinle Representational Style, best illustrated in Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto. In these examples they are often portrayed as the heads of anthropomorphs. “Most have crescent-shaped or semicircular bodies, and the heads and necks of many were painted with a fugitive, or impermanent, red pigment that has since flaked away while the body shape remains.” (p. 125)

Commenting

on turkey pictographs at Tsegi Canyon and Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, Shaafsma

wrote “The turkey, a creature of the

earth (as opposed to the sky), is bound to embody a different set of symbolic concepts,

although this bird too is found in the

same set of relationships to human figures in the rock art. The turkey was

domesticated by the Anasazi by A.D. 700. Its feathers were used for robes and

ritual purposes at least by that time and perhaps even earlier. Among the

modern Pueblo Indians, the turkey is symbolically associated with the earth,

springs, streams and mountains which are the homes of the cloud spirits. It

follows that the turkey is viewed as an intermediary between these mountain

water sources and the rain clouds that form on the peaks. He is also regarded

as a teacher and a helper, and is associated with the dead who must return to

the earth before as rising as clouds to the spiritual realm.” (Schaafsma

1986:27-28)

Long House, Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico. Petroglyphs of male turkeys with fanned tails and wings arched in display. Rohm, p. 57. Photograph by Peter Faris, 1985.

Closeup, Long House, Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico. Petroglyphs of male turkeys with fanned tails and wings arched in display. Internet photograph, public domain.

These two birds in the Mortandad Canyon Cave Kiva, New Mexico, are in a stance suggesting they are grounded. The upper bird is a male turkey. Rohm, page 106, photograph by Wm. M. Ferguson.

On New Mexico’s Pajarito Plateau “The most impressive birds of the region are flocks of wild turkeys. They range into the higher elevations of the Jemez Mountains during summer, but descend to the plateau and canyons during the cold and snowy weather where they feed on nuts, acorns and berries.” (Rohn 1989:4) Of the above photograph of birds from Bandelier National Monument Rohn stated “These two standing birds – must depict male turkeys with their tails fanned out and their wings arched in their display stance.” (Rohn 1989:57)

So, where they existed, turkeys would have been a major resource. Although there is still debate over how much Ancestral Puebloans relied on them for food, their feathers for ritual use and for the manufacture of feather blankets were of considerable importance, and their bones could be turned into whistles and tool, but with my favorite holiday being Thanksgiving, I do hope that these people availed themselves of the feast of roasted turkey once in a while.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

PRIMARY REFERENCES:

Conrad, C., 2021, Contextualizing Ancestral Pueblo Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo spp.) Management, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-021-09531-9

Robins, Michael R., and Kelley A. Hays-Gilpin, 2000, The Bird in the Basket, in Foundations of Anasazi Culture: The Basketmaker – Pueblo Transition, edited by Paul F. Reed, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, p. 231-247.

Rohn, Arthur H., 1989, Rock Art of Bandelier National Monument, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Schaafsma, Polly, 1980, Indian Rock Art of the Southwest, School of American Research, Santa Fe, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Tyler, Hamilton A., 1991, Pueblo Birds and Myths, Northland Publishing Co., Flagstaff, AZ.

SECONDARY REFERENCE:

Schaafsma, Polly, 1986, Anasazi Rock Art in Tsegi Canyon and Canyon de Chelly: A View Behind the Image, In Tsa Yaa Kin: Houses beneath the Rock, edited by David Grant Noble, School of American Research, Santa Fe.

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)