I have previously written a number of columns in RockArtBlog about handprints (see hand print in the cloud index at the bottom of the page with a couple more under gender). Subjects have included determining gender from handprints, handedness from handprints, and handprints as a system of numerical notation. Many handprints (especially in the Paleolithic painted caves of Europe) are incomplete showing apparently missing finger joints of whole fingers. Various reasons for this have been proposed including fingers missing because of injury or fristbite, and counting systems where whole fingers and folded fingers represent differing numbers in a notation.

A 2018 paper published online brought out a new proposal for the reason we find hendprints with missing finger joints or fingers. McCauley et al. (2018) studied the phenomenon of phalangeal amputation across a broad range of indigenous cultures and identified seven separate reasons for the removal of finger joints among these peoples.

Sacrifice: the amputation to appeal to a deity for assistance. The most common type of finger amputation, they found thirty-three groups that practiced this: sixteen from North America, ten from Africa, six from Oceania, and one from Asia. More common in females than in males, it was also more common in children than adults. Typically the distal phalanx of the fifth finger would be removed from one hand or the other. (McCauley et al. 2018) An example would be members of the tribes of the Great Plains of North America who would sometimes remove a finger joint during the Sun Dance to appeal to the Great Spirit.

Mourning: wherein close relatives of a deceased individual would remove finger joints as an actd of extreme grief. Thirty groups displayed this practice: fifteen from North America, six from Africa, six from Oceania, and three from South America. (McCauley et al. 2018)

Identity: finger amputations carried out to mark group membership. Nineteen groups in their sample engaged in this practice: nine from Australia, eight from Africa, and two from North America. (McCauley et al. 2018)

Medical: in this practice finger amputation was used to resolve a health problem. It not only includes fingers that have been physically damaged (e. g. frosbitten or crushed) but also amputating undamaged fingers to bleed sickness out. Twelve groups engaged in this practice: eight from Africa, two from North America, one from Eurasia, and one from Oceania. (McCauley et al. 2018)

Marriage: This was removal of a phalange prior to the amputee getting married. This was engaged in by two groups; one from Africa, and one from Australia. In both cases it was female specific and involved the removal of the distal phalanx of the left hand. In both of these groups it was carried out by tying a cordd tightly around the finger until the phalange fell off. (McCauley et al. 2018)

Punishment: Twenty three groups practiced finger amputation as a form of punishment: sixteen from Africa, four from Asia, two from North America, and one from Oceania. (McCauley et al. 2018)

Veneration: McCauley et al. found one example of this from North America. In this case and elderly Sioux woman cut off all the fingers of some Chippewa children and strung them on a ritual necklace. (McCauley et al. 2018)

McCauley et al. also recorded some instances of the practice of amputating fingers of an individual after death but these would be irrelevant to this practice because we would not expect a dead person to be leaving handprints in a cave.

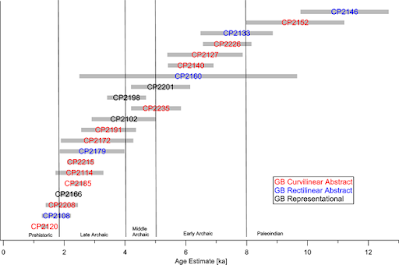

"We identified 121 groups that engaged in finger amputation at the time they were studied by ethnographers. Among these groups there were ten different reasons for engaging in finger amputation. Of these ten, the one that best fits the available data for the UP (Upper Paleolithic) incomplete hand images is voluntary sacrifice to a deity or supernatural power." (McCauley et al. 2018) So, based on this study, we have a new candidate for the reason some handprints show missing fingers or joints - voluntary sacrifice.

This comprehensive study illustrates the difficulty of interpreting the moteve from just the image. Far from proving either frostbite, or a counting system, a missing finger could represent any of these seven cultural practices, as well as indicating frostbite, or a counting system. It is just not as simple as it looks.

NOTE: Some images in this

posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain

photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I

apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will

contact me with them. For further information on this subject you should read

the original report at the site listed below.

REFERENCES:

McCauley, Brea, David Maxwell and Mark Collardi, 2018, A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Upper Palaeolithic Hand Images with Missing Phalanges, published online 21 November 2018, Journal of Palaeolithic Archaeology, Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)