I have written before on the subject of comets pictured in rock art here on RockArtBlog. I find the concept of an astrophysical manifestation like a comet being recorded in this way to be eminently reasonable, something as amazing as a close approach of a comet might well spark the desire to make a record.

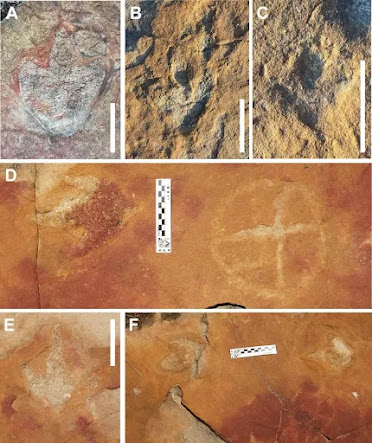

One apparently memorable comet appearance was in 1264 AD. This one was supposedly seen pretty much worldwide, and mentioned in records. According to Herman E. Bender “Unambiguous images of comets in North American rock art are rare. What is or may well be even more rare to non-existent was/is the ability to date the images. This potentially changed with discovery in or about 2013 of a comet pictograph near Los Alamos, New Mexico. The comet in the pictograph was identified by a scientific team as the Great Comet of 1264 AD. Backing up the claim, European and Asian medieval comet records firmly indicated the comet had entered eastern Orion in mid-August and had five tails. Because three stars in a row, i.e. Orion’s ‘belt stars’, were indicated on the rock art panel along with the comet and its five tails, the comet in the pictograph was dated to mid to late August, 1264 AD.” (Bender 2023:21)

Here Bender is correlating the vertical row of three dots below the supposed image of the comet to the belt of the constellation Orion.

One interesting identifying feature of the comet portrayal is that it is shown with five lines of dots that are taken as its tails. “Five tails was a salient feature of the Great Comet of 1264 AD. The Korean records stated that, ‘On a chia-hsi~ day in the seventh month of the fifth year of WSnjong [26th July] a comet was observed at the NE. Its tail, which measured 7 to 8 ft, gradually divided itself into five branches pointing towards the NW.’ Further corroborating the five tails time-line for August 17 (1264 AD), the Korean record went on to state that, ‘On a jen-yin day in the eighth month [23rd August] the [five] branches reunited and the tail increased in length.’ The European records leave no doubt that the comet sported five separate tails, but also echo Asian records of where the comet was seen with its five tails on the early morning of August 17, 1264 AD, i.e. ‘between the Dog [Sirius and Canis Major] and Orion’.” (Bender 2023:21-22) I have so far been the actual dating method used to reach this conclusion, however, Bruce Masse (2013) implies that it was estimated based on the position of the comet to a supposed indication of the constellation Orion on the panel. This position was also found in the Korean record.

The remarkable appearance of this comet would have been memorable indeed. Donald K. Yeomans (2007) reported that “on July 26, Chinese observers reported the tail spanning 100 degrees.” This is obviously an extremely impressive manifestation with it spanning 100 degrees across the arc of the sky. This appearance was well recorded with J. R. Hind citing over three dozen contemporary sources in his 1884 book On the expected return of the great comet of 1264 and 1556.

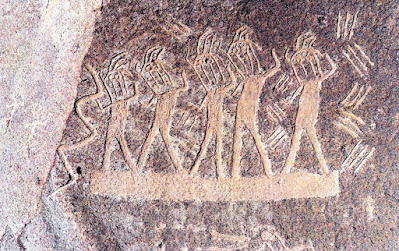

As I had stated above, I find the concept of an astrophysical manifestation like a comet being recorded in this way to be eminently reasonable, something as amazing as a close approach of a comet might well spark the desire to make a record. A more famous example of such a record is the fresco painting Adoration of the Magi by Giotto di Bondoni in 1301 in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy. In this, Bondoni shows the magi before the Holy Family in the manger with the Star of Bethlehem shown in the form of a comet.

Having been lucky enough to have seen a few comets in my life I can well understand the urge to leave a record of such a wondrous occasion. While I have not always totally agreed with Bender’s analyses in other things I can find no reason to disagree with this one. Congratulations to all involved in winkling out the facts to this fascinating story.

NOTE 1: If you wish to refer to P. Andrew

Karam’s (2017) book on comets be sure to check pages 66 and 67 where he has

included my photograph and field sketch of the great comet from the famous

panel in Chaco Canyon.

NOTE 2: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Bender, Herman E., 2023, The Great Comet of 1264 AC in Rock Art – Two Views from North America, Hanwakan Center for Prehistoric Astronomy, Cosmology and Cultural Landscape Studies, Inc., Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, USA. Accessed online 14 September 2024.

Hind, J. R., 1848, On the expected return of the great comet of 1264 and 1556, Published by G. Hoby, 123 Mount Street, Berkeley Square, London. Accessed online 6 August 2025.

Karam, P. Andrew, 2017, Comets, Reaktion Books, London.

Masse, W. Bruce et al., 2013, A Probable Ancestral Pueblo Comet Petroglyph at Los Alamos National Laboratory, PowerPoint presentation at IFRAO 2013 conference, American Rock Art Research Association, Glendale, Arizona. Accessed online 7 August 2025/

Yeomans, Donald K., 2007, Great Comets in History, from Solar System Dynamics, Jet Propulsion

Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Accessed online 6 August 2025.

.jpg)