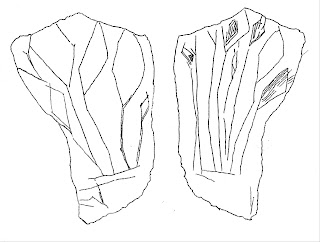

James Ragen inscription, Bent's New Fort, CO.

Photo - Bill McGlone.

This inscription is carved on the cliff along the Arkansas River near the site of Bent’s New Fort, located a few miles downriver from Bent’s Old Fort. In the late 1840s Indian troubles caused a decline in trade, which made Bent’s business unsustainable. Wm. Bent attempted to sell it to the army but they would not meet his price so in 1849 he blew the fort up. In 1853 Bent built a new stone fort to the east of the old fort in what is now Prowers County, Colorado. In 1860, Fort Wise was established by the US Army one mile west of the site of Bent’s New Fort and in 1861 its name was changed to Fort Lyon. William Bent left his new stone fort and rented it to the army as a storage depot. He retired to a farm at Boggsville, along the Purgatory River. Unfortunately Fort Lyon had been built too near the river and in early 1865 a spring ice dam on the Arkansas River backed the river up and flooded the buildings. The fort was moved to a new site near Las Animas in Bent County, Colorado in 1865.

Old Fort Lyon, fr. Hyde, The Life of Geo. Bent, 1968.

The Second Colorado Cavalry was organized in October 1863, in St. Louis, MO, by consolidation of the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Regiments. James Ragen enlisted with the rank of Private and was assigned to Company H. Companies F, G, H, and K, were on duty in Colorado at Fort Lyon and other points until November 1863. “Company K stayed at Fort Lyon till the month of November; then Companies F, G, and H of the Third Regiment, in obedience to general order, concentrated with Company K of the Second at Fort Lyon and received orders to march for the States. Accordingly, on the twentieth day of November, 1863, with Major Pritchard in command, we started at noon and made about twelve miles.” While Company K of the Second Colorado was crossing the Plains the rest of the regiment, including Company H which was already on duty in Arkansas, received orders to march to Kansas City preparatory to consolidation. Another trooper in Company H of the Second Colorado Cavalry was John Johnson, otherwise known as “liver-eating” Johnson, the notable mountain man and the model for the character of Jeremiah Johnson in the movie of the same name.

Lt. Col. Theodore Dodd (L.) and Col. James H. Ford (R.),

photo archived at Carlisle Barracks.

“The first and only colonel of the regiment was James H. Ford, Theodore Dodd was the lieutenant colonel. At the time of the consolidation Company A of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry (Dodd’s former company) became Company B of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry. Company B of the 2nd Colorado Infantry (originally Ford’s Independent Company) became Company A of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry.” In January, 1864, the 2nd Colorado Cavalry was ordered into the Missouri border counties to fight against Confederate “bushwhackers” and in October, 1864, was part of the Union force raised to repel the Missouri invasion of Confederate General Sterling Price. When he withdrew, the 2nd Colorado Cavalry joined the pursuit, meeting his forces for the last time near Fayetteville, Arkansas, in November 1864.

In December 1864 they were moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where Colonel Ford, with the Brevet rank of Brigadier General, commanded the military district of the Upper Arkansas. The 2nd Colorado Cavalry was largely devoted to escorting supply and wagon trains, and occasionally skirmishing with Indians. At Fort Riley, Kansas, there were eight companies of the 2nd Colorado, accompanied by one section of the 9th Wisconsin Artillery. Two companies of the 2nd Colorado were also stationed at Fort Larned with one company of the 12th Kansas Cavalry, one company of the 11th Kansas Cavalry, and one section of the 9th Wisconsin Artillery. On December 31, 1864, Col. Ford had 24 officers and 803 men present, able for duty, and in the saddle. Of course, there were many not in the saddle.

The last troops of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry were mustered out in September 1865 leaving this inscription as a tangible record of the events. It reminds us of the history of the area, and gives us a peek into the complicated stories of the early years of American settlement of the West.