A team of archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute and Saudi Arabian Commission for Tourism and National Heritage has been recording rock art in Northwestern Saudi Arabia.

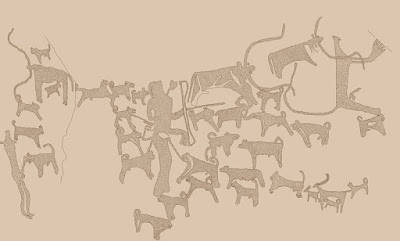

One fascinating category of images

consists of hunting scenes in which bow and arrow armed humans are accompanied

by dogs, some of which seem to have lines connecting them to the hunters – a

leash? They also believe that according to their estimated age of these

petroglyphs that they represent the oldest known portrayals of canines, at

least domesticated canines.

“The hunting scene comes from Shuwaymis, a hilly region of

northwestern Saudi Arabia where seasonal rains once formed rivers and supported

pockets of dense vegetation. For the past 3 years, Maria Gaugnin, and

archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in

Jena, Germany – in partnership with the Saudi Commission for Tourism &

National Heritage – has helped catalog more than 1400 rock art panels containing

nearly 7000 animals and humans at Shuwaymis and Jubba, a more open vista about

200 kilometers north that was once dotted with lakes.” (Grimm 2017)

Climatic warming has severely dried

this area to what is now more like arid desert, but in the past it was wetter

and with more vegetation to encourage animal life.

“Starting about 10,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers entered –

or perhaps returned to – the region. What appear to be the oldest images are

thought to date to this time and depict curvy women. Then about 7000 to 8000

years ago, people here became herders, based on livestock bones found at

Jubbah: that’s likely when pictures of cattle, sheep, and goats began to

dominate the images. In between – carved on top of the women and under the

livestock – are the early hunting dogs: 156 at Shuwaymis and 193 at Jubbah. All

are medium-sized, with pricked up ears, short snouts, and curled tails –

hallmarks of domestic canines. In some scenes, the dogs face off against wild

donkeys. In others they bite the necks and bellies of ibexes and gazelles. And

in many, they are tethered to a human armed with a bow and arrow.” (Grimm 2017) So, in a considerable array of canine images, some few

are connected to human figures by lines or tethers which are considered to be

possible leashes while most are not.

“We already knew that

pre-Neolithic humans used domesticated dogs for hunting purposes, but details

about how exactly they went about this have remained unclear. The 147 hunting

scenes the researchers have been studiously documenting at sites in Shuwaymis

and Jubbah, in northwestern Saudi Arabia, show a range of possible roles. A

paper detailing the research was published in the Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology. ‘When (corresponding author Maria Guagnin) came to me with the

rock art photos and asked me if they meant anything, I about lost my mind,’

co-author Angela Perri, who studies animal archaeology at the Max Planck

Institute for Evolutionary Archaeology in Leipzig, Germany, told Science

Magazine. ‘A million bones won’t tell me what these images are telling me,’ she

says. ‘It’s the closest thing you’re going to get to a YouTube video.’” (Medrano 2017)

No dating is available for these

ancient petroglyphs so the researchers had to estimate their potential ages by

looking at the stratigraphy of the rock art itself (the sequence in which the

images were carved). “The researchers

couldn’t directly date the images, but based on the sequence of carving, the

weathering of the rock, and the timing of the switch to pastoralism, ‘The dog

art is at least 8000 to 9000 years old,’ Guagnin says. That may edge out

depictions of dogs previously labeled the oldest, paintings on Iranian pottery

dated to at most 8000 years ago.” (Grimm 2017)

“Even if the art is younger than Guagnin and her colleagues think, the leashes are by far the oldest on record. Until now, the earliest evidence for such restraints came from a wall painting in Egypt dated to about 5500 years ago, Perri says. The Arabian hunters may have used the leashes to keep valuable scent dogs close and protected, she says, or to train new dogs. Leashing dogs to the hunter’s waist may have freed his hands for the bow and arrow.” (Grimm 2017) Here, the writer is implying that the hunters used two types of dogs, or had dogs fulfilling two roles. The “scent dogs” would be the ones with the most sensitive noses for tracking by scent, while the other “sight hounds” would be the pack of visual hunters who handled the pursuit and cornering of the game. Some game animals could actually be taken down by the pack while larger game such as aurochs could be cornered until the hunters came up with weapons to end the confrontation. Grimm is also implying that the “scent dogs,” being more valuable, were the ones on the leash while the pack hounds were free to pursue, corner, and possibly be injured by large game.

“Dogs can realize a decrease in search costs and an increase

in prey encounter rates by flushing and finding animals. These characteristics

may be especially important with pedestrian hunts where pray resources that are

highly dispersed or have low densities, are cryptic or fossorial, and/or occupy

biomes with heavy vegetation and rugged terrain. Reductions in search costs

become less beneficial with prey that use habitual paths or runways or that are

highly predictable in location and where hunting require(s) stealth and ambush

strategies and the use of some stationary technology (traps, snares). Dogs can

also reduce the handling costs association with prey acquisition by distracting

or baying dangerous animals, pursuing wounded prey and finding carcasses of

animals that have been killed. The latter characteristics are especially

advantageous with the use of certain kinds of dispatch technology that do not

always immediately kill the animals, such as poisoned arrows or in heavily

vegetated areas and rugged terrain where locating dead animals is difficult.

The ability of dogs to chase and locate a wounded and dying animal or the

carcass of one that has died from its wounds is a critical factor that reduces

the chances of hunting failure and improves success.” (Lupo 2017) While all of these factors are germane, Lupo

overlooks the value of the “scent dogs” in following a game animals trail in

situations where visual clues are absent. This is also one method in which the

dog can locate the “wounded and dying animal” mentioned, by following the

scent.

“The dogs look a lot like today’s Canaan dog, says Perri, a

largely feral breed that roams the deserts of the Middle East. That could

indicate that these ancient people bred dogs that had already adapted to

hunting in the desert, the team reports in the Journal of Anthropological

Archaeology. Or people may even have independently domesticated these dogs from

the Arabian wolf long after dogs were domesticated elsewhere, which likely

happened sometime between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago.” (Grimm 2017) The existence of the Canaan dog in Arabia is known

from at least 9000 years ago. “The Canaan

Dog is the oldest breed of pariah dog still existing and abundant across the

Middle East. It can be found in Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and the

Sinai Peninsula, and these, or dogs nearly identical were also found in Iraq

and Syria over 9000 years ago.” (Wikipedia)

The origins of the domesticated dog have

been much in the news (at least the scientific news) of late and that question

has not yet been settled, but, for now, it appears that we do know the first

rock art picturing domesticated dogs.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Grimm, David, 2017, These may be the world’s first images of dogs – and they’re wearing

leashes, 16 November 2017, https://www.science.org

Lupo, Karen D., 2017, When and where do dogs improve hunting productivity? The empirical

record and some implications for early Upper Paleolithic prey acquisition,

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 47 (2017) 139-151.

.jpg)