The latter stages of the Narrative Mode of Plains Biographic Style art represent story-telling and the recording of deeds and events. One excellent example is 5LA8464, the Box Canyon Site.

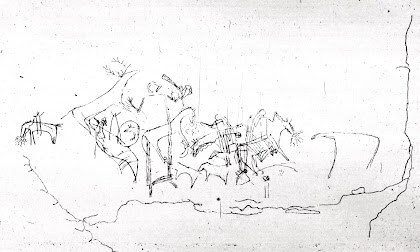

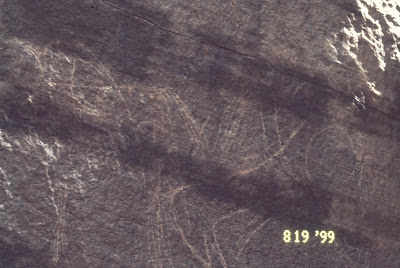

The recently discovered (1998 or 1999, recent as of when this was first written) Box Canyon Site (5LA8464) in the Picketwire Canyonlands of the Purgatoire River valley has a lightly engraved panel of Plains Biographic images. It consists of a single, large rectilinear-bodied anthropomorph with a complex composition lightly engraved over it with a number of equestrian figures, and elk, a bear, probable horses, and a probably tipi, and it displays narrative details that suggest decipherable meaning.

Two equestrian figures on the right are surrounded by riderless horses that may represent horses captured on a horse raid. One of the equestrian figures wears Paynee-style cuffed moccasinns (Afton et al. 1997:18), and both horsemen on the right side of the panel wear long, trailing scalp locks that are also often identified as Pawnee (Afton et al. 1997:18). One of these horsemen fires a rifle toward the horseman on the left side of the panel. Additionally, these figures have zigzag reins which may symbolize lightning power. In Black Elk's 'Horse Dance', which re-enacted his vision, the horses were painted with lightning stripes and hail spots (Brown 1997:58). Lightning stripes were also a common theme on horses painted for war (Mails 1991:223). The two horses with riders on the right, the horse with an incomplete rider partly obscured by the large figure in the center, and the horse with a rider on the far left are equipped with decorated halters. Jim Keyser (1991:261, 1987:57-58) stated that "one of the most common pieces of horse gear depicted in Biographic Style art is a decorated halter." The decorated bridles at the Box Canyon Site were described by Keyser and Mark Mitchell (2001:202) as "wavy, dangling chains" and were compared to examples drawn on a pawnee decorated robe illustrated by John Ewers (1939:Pl.23).

On the left side of the panel one figure on horseback in front of the tipi probably represents the defense of the village (this horse is incomplete). The figure has been struck by and arrow which sticks in its chest. This composition may, in fact, represent a Pawnee horse raid on another tribe's village. From the location and age of the panel it is likely that this resident tribe was Cheyenne or Arapaho, the primary residents of the area during the later historic period.

As stated above, the mode of portrayal (Iconic or Narrative) of horses in rock art suggests the stage of assimilation of the horse into the society that produced that rock art.

While scholars all agree that the horse had a tremendous effect upon the cultures of the tribes of the original peoples of the Great Plains, just what that effect was is still argued. One side maintains that the horse was merely a cause of intensification, a catalyst as it were, for traits that were already present among the tribes (Carlson 1998:39, Mails 1991:216, Roe 1955:179), while the other side sees the horse as the stimulus to the radical revolution that completely remade the cultures of the peoples of the Great Plains from pedestrian semi-horticulturists to the height of their lives as the Horse Tribes of the late 17th to late 19th centuries (Harrod 1987:9, Mayhall 1987:109).

As is so often the case in such debates, there is truth in both positions. In the beginning the Indians accepted the horse as a wonderful convenience, and fit it into their lifestyle as it then existed. The horse began as a tool that allowed them to do many things better than before: when pulling a travois it could handle a much bigger load than any dog; for hunting buffalo it made the hunt more reliable by its ability to cover large distances and possessed the speed to run down the quarry; and in war it magnified the striking power of the warrior and vastly enlarged the area he could fight over. In the process the horse remade the cultures and societies of the peoples of the Great Plains.

In the end, the effect of the horse on the people of the Great Plains can perhaps be likened to the effect of the automobile on the culture of 20th century America. At first, in a horse and buggy culture, the automobile was used as local transportation of questionable reliability. Indeed, its early designation of "horseless carriage" is a striking parallel to Indian names such as "elk dog" for the horse. The automobile went on to grow in importance until it became a major factor in molding societal and cultural change; look at the effect of the interstate highway system on the society of America and its urban landscape. The automobile, like the horse, was an improved means of transportation and could haul more goods and possessions, which greatly affected the economy. The automobile, like the horse, has revolutionized warfare; and the automobile, like the horse, has become an indicator of wealth. By the middle of the 20th century teenage boys dreamed of owning their first car the way that young Indian boys must have dreamed about owning horses and, like the early days of the automobile, conservative tribal elders had probably predicted that the horse was merely a passing fad.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Ewers, John C., 1939, Plains Indian Painting, A Description of an Aboriginal American Art, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

Harrod, Howard L., 1987, Renenewing the World, Plains Indian Religion and Morality, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Keyser James D.

1991, A Thing to Tie on the Halter: An Addition to the Plains Rock Art Lexicon, Plains Anthropologist, 36(136):261-267.

1987, A Lexicon for Historic Plains Indian Rock Art: Increasing Interpretive Potential, Plains Anthropologist, 32(115):43-71.

Keyser, James D. and Mark Mitchell, 2001, Decorated Bridles: Horse Tack in Plains Biographic Rock Art, Plains Anthropologist, 46(176):195-210.

%20-%20Copy.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment