Did Albert Einstein really come up with the Theory of Relativity (his famous E=MC2) first?

In the August 2015 issue of Scientific American magazine, Tony Rothman had an article asking “Was Einstein the First to Invent E=mc2?” Rothman pointed to a number of mathematicians that had played around with formulae approaching that over the years.

“Anyone who sits through a freshman electricity and magnetism course learns that charged objects carry electric fields, and that moving charges also create magnetic fields. Hence, moving charged particles carry electromagnetic fields. Late 19th-century natural philosophers believed that electromagnetism was more fundamental than Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and that the electromagnetic field itself should provide the origin of mass. In 1881 J. J. Thomson, later a discoverer of the electron, made the first attempt to demonstrate how this might come about by explicitly calculating the magnetic field generated by a moving charged sphere and showing that the field in turn induced a mass into the sphere itself.” (Rothman 2015)

“When Englishman John Henry Poynting announced in 1884 a celebrated theorem on the conservation of energy for the electromagnetic field, other scientists quickly attempted to extend conservation laws to mass plus energy. Indeed, in 1900 the ubiquitous Henri Poincaré stated that if one required that the momentum of any particles present in an electromagnetic field plus the momentum of the field itself be conserved together, then Poynting’s theorem predicted that the field acts as a “fictitious fluid” with mass such that E = mc2. Poincaré, however, failed to connect E with the mass of any real body.” (Rothman 2015)

Albert Einstein finally cleared up the loose ends in 1915. "He produced in time for his final lecture on November 25 (1915) - entitled "The Field Equations for Gravitation" - a set of covariant equations that described the general theory of relativity. It was not nearly as vivid to the layperson as, say, E=mc2. Yet using the condensed notations of tensors, in which sprawling mathematical complexities can be compressed into little subscripts, the crux of the final Einstein field equation is complex enough to be emblazoned on T-shirts worn by physics geeks. In one of its many variations , it can be written as: Rµν -1/2gµνR= -8 πGTµν. The left side of the equation - which is now known as the Einstein tensor and can be written simply as Gµν - describes how the geometry of spac time is warped and curved by massive objects. The right side describes the movement of matter in the gravitational field. The interplay between the two sides shows how objects curve spacetime and how, in turn, this curvature affects the motion of objects."(Greene 2015:43).” (Isaacson 2015)

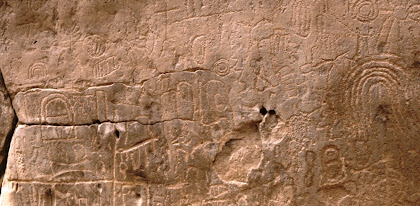

A group of researchers have spent years investigating abstract inscriptions pecked into the rocks of southeast Colorado, particularly focusing on ones that appear to be lines of script that some of them liken to various northern Arabian scripts such as proto-Phoenician and others even earlier. Now, we all know that the ancient inhabitants of Arabia were quite sophisticated in mathematics. In the centuries before Christ inhabitants of the Fertile Crescent invented many of the mathematical techniques still used today.

This brings me to the particular inscription from the Picketwire Canyonlands illustrated above. If this could be proven to be a variant of one of the northern Arabian scripts, when compared to Einstein’s formula it seems to show an uncanny resemblance. Could this be the work of an Archaic mathematical genius in southeastern Colorado? You be the judge on this First of April.

NOTE: I added the equivalency symbol (=) in the last illustration to help clarify the concept for April 1. These petroglyphs had been highlighted with aluminum paint by persons unknown some time back in the 1980s I believe (I am pretty sure I do know who but they have never admitted to anything). There had been a short fashion of highlighting petroglyphs with aluminum powder mixed with water that some students of rock art flirted with before they realized that it would change the chemistry of the patina. They believed that the next rain would wash everything away doing no damage. In my opinion someone new to the field misinterpreted that to mean aluminum paint.

REFERENCE:

Isaacson, Walter, 2015, How Einstein Reinvented Reality, September 2015, Scientific American, Volume 313, No. 3, pp. 38-45.

Rothman, Tony, 2015, Was Einstein the First to Invent E=mc2?, 18 August 2015, Scientific American, Volume 313, No. 3.

SECONDARY REFERENCE:

Greene, Brian, 2015, Einstein: Why He Matters, Scientific American, Volume 313, No. 3, Sept. 2015, pages 34

- 37,

No comments:

Post a Comment