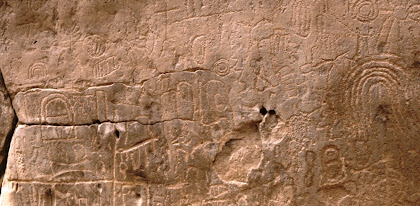

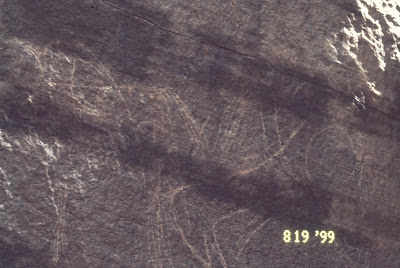

The whole field of archeoastronomy is interesting, but a little like analyzing Rorsach Blots. What people see is influenced by what they expect (or want) to find when they are looking at possible examples. One good example is outlined in the citation below:

“Two couples of stone disks found at the entrances and cemeteries of protohistoric hill forts in the north-eastern Adriatic area were suggested to have a symbolic meaning representing the Sun and the Night Sky. In one pair the night sky is symbolically represented by a number of natural holes made by marine bivalves but in the other stone studied here the marks are made by a human hand and show a pattern. We performed a statistical comparison of the chisel marks with the most common asterisms to try to establish if they were randomly made or they had some intentionality.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:11) Notice that Molaro and Bernardini said “the night sky is symbolically represented by a number of natural holes made by marine bivalves.” In other words, clams or barnacles have bored into the surface of a piece of stone in the pattern of asterisms in the night sky. The authors used statistical analysis to identify the patterns. Any time statistics enters the picture I get skeptical. A good mathematician can use statistics to make the answers come out any way they wish. I wonder if the marine bivalves also used statistics to plot where they should bore their holes.

“The whole pattern is composed by 29 chisel marks, 24 in the front face of the stone and 5 on the back. 28 chisel marks are consistent with the asterisms of Scorpius, Orion, Pleiades and, perhaps, of Cassiopeia on the back side of the stone. The correlation between the chisel marks and the stellar position is very high with r(28) = 0.994. The p-value is formally 0.001 and provides a very low probability that the chisel marks were produced accidentally.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:11) The authors suggest the age of these stones as Bronze Age. They also state that there are no written records from the local cultures during that time period. I, then, need to ask how they can know what stellar asterisms the inhabitants of the hill fort would recognize and wish to record?

“One chisel mark remains without an obvious identification. This is the most problematic chisel mark to explain.The mark is close to the stellar system of 𝜇 Ori, formed by two physical binary systems with an integrated magnitude of V = 4.1. Alternatively, if it belongs to the portion of sky of Scorpius it could be associated to 𝜖 Sgr. However, all these identifications are quite unsatisfactory. One intriguing possibility is that a bright star was present in that position that produced a supernova or more likely a failed supernova leaving a black hole as a remnant. Interestingly, this prediction could be tested through detailed observations and, therefore, specific studies are solicited.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:11) One mark does not fit their theory, therefore, it may have disappeared in the interim in a supernova? This strikes me as really stretching to make your point.

“The asterisms are quite complete showing all the bright stars. Notable missing are 𝛾 and 𝜅 Ori. However, the location is in the most exposed part of the stone and the mark could have been possibly deleted by stone erosion.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:11) Even more convenient, not only has a supernova since made one star disappear that was carved onto the stone, but erosion has removed a couple of important stars that should be there.

“The deviations from real positions are of about one degree which are comparable with the size of the marks in the stone. For comparison, in the catalogue of Ptolemaios the error distributions is of 27 and 23 arcmin in longitude and latitude respectively, which is only about a factor 2–3 better than those on the stone. This requires a careful preparation and patient persistence in the execution. As such, the reproduction is not symbolic but faithful, showing an effort in providing the true stellar positions in the sky.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:11-12)

Now, all of this may, in fact, be true, but I am not convinced. These stone disks may be ancient star charts with all of this archeoastronomical data recorded on them. The authors pointed out a likeness of these stone disks to covers for Roman Era shaft tombs, and we know the Romans recognized many of the same asterism as we do. “However, after the work of Bernardini et al. (2022), round stone artefacts of similar shape and dimensions were identified in the collection of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Aquileia. Probably they are roughed-out blocks for lids for circular tombstones. Since the exact archaeological context of the stones from Rupinpiccolo cannot be determined with precision, the possibility of Roman origin cannot be ruled out.” (Molaro and Bernardini 2023:2) I truly do not know any of this with any real certainty, and I submit, the Molaro and Bernardini may be a little too eager in their interpretations. At least they admit to a certain amount of speculation. After their paper was released popular press stories popped up which address this whole question as the proven truth. Which takes me back to the Rorsach Blots – we see what we want to see.

NOTE 2: Images used are from the Primary Reference paper. by Molaro and Bernardini.

PRIMARY REFERENCE:

Molaro, Paolo, and Frederico

Bernardini, 2023, Possible stellar asterisms carved on a

protohistoric stone, 6 November 2023, Astronomical Notes (Astron Nachr),

DOI:10.1002/asna.20220108. Accessed online 25 December 2023.

SECONDARY REFERENCE:

Bernardini, F., Vinci, G., Macovaz, V., Baucon, A., De Min, A., Furlani, S., and Smolic, S., 2022, Doc Praehist, XLIX, 2.

%20-%20Copy.jpg)