On 28 July 2018, I posted a column titled The Paleolithic Unicorn – Found At Last, about the enigmatic painting of an animal in Lascaux Cave in France that has straight horns coming straight forward out of his head and who is sometimes called the Lascaux Unicorn. I likened it to the extinct Elasmotherium, a relative of the rhinoceros with a single horn, sometimes called the Paleolithic unicorn. While I was in no way expressing the opinion that the animal pictured in Lascaux was meant to represent an Elasmotherium, I was making the point that there had been a single-horned animal back millennia ago, and the curious coincidence of the naming of that Lascaux beast’s image. (Faris 2018)

In this column, however, I am going to look at rock art of single-horned animals from South Africa, originating in San mythology. It has often been assumed that the image of a single-horned quadruped may have originated with something like an oryx seen from the side with its horns perfectly aligned. This may be part of the story, and there are San representations of antelope-like animals seen from the side with only one horn represented. It also needs to be pointed out that these San examples have the horn projecting backwards from its natural head location, not forward from the forehead as in the European belief in unicorns. It may be, however, that European visitors to such rock art sites might interpret them as portraying some version of the unicorn they believed in so fervently.

“Europeans sought unicorns and rock paintings of them almost as soon as they set foot on the shores of southern Africa. Their interest stemmed from their cultural beliefs, which they transposed onto the African continent and its people. Against this Western backdrop, many early travelers searched for rock paintings of unicorns, which some considered evidence of the creature’s existence. – Rock paintings have thus played a significant role in South Africa’s unicorn lore. - Ultimately, however, the images were dismissed as depicting figments of the imagination. For centuries, colonial beliefs about unicorns silently mixed with indigenous ones. But, whereas physical proof became Holy Grail, indigenous beliefs were regarded skeptically as rumor or hearsay. Without realizing this distinction, European colonists sought after the unicorn, assuming, at least initially, that it was the creature they knew.” (Witelson 2023:2) The hubris of the colonials inevitably looked to European ‘scientific knowledge’ as more true and real than indigenous knowledge about their own territory.

“Perhaps the most famous South African search for unicorns was reported by John Barrow, ‘Late Secretary to the Earl of Macartney, and Auditor-General of Public Accounts, at the Cape of Good Hope.’ He sought evidence for real rather than fanciful unicorns, which he considered of potentially biblical importance to Natural History. Any biological specimen would therefore have had a place in the nascent world of European science. Barrow thought the ‘living original’ might yet be found north and east of the Bamboesberg mountain range in what is today the Eastern Cape Province. There, ‘the people [Bosjemans or Bushmen] who make them [the paintings] live.’ Although he managed to arouse some enthusiasm for an expedition to go in search of it, he never ventured east outside the Colony.” (Witelson 2023:3) In this case the fact that unicorns were mentioned in the bible became a colonial ‘scientific truth’ where the beliefs of locals were essentially eventually discounted as superstition.

“Locals must have noticed something interesting about the British when they first arrived. They wore symbols on their uniforms of familiar animals, the lion and the unicorn. The British were likely amazed that the locals were aware of unicorns, and could even describe them in detail. Then the discovery by colonists of ancient rock art – depictions of unicorns as commonplace animals – caused imaginations to race. What followed were concerted search efforts fueled by a desire to capture a creature of both biblical importance and interest to natural history scientists. It was biblical passages that led to the unicorn being adopted as a royal symbol, and any question of the creature’s reality was, especially in light of new evidence, necessarily so.” (Jackson 2023)

Barrow did manage to visit several rock shelters eventually, and produced a sketch of a very Western-looking unicorn, the original for which has never been found, and is widely considered to have been either a hoax or overactive imagination in interpreting a very damaged rock art image. (Witelson 2023) “The cynical views of Barrow’s and other unicorn images are partly rooted in a perspectival argument: because the animal is depicted side-on, one horn obscures the second. It is one of three explanations that arose when, unsurprisingly, the ‘real’ unicorn was not found. One claimed, as we have seen, that the rhinoceros had been the unicorn all along. A second, which we have also encountered, suggests that the gemsbok was the inspiration behind the unicorn because one straight horn covers the other when viewed from a lateral perspective, and males often lose a horn in the rutting season. A third claimed that the unicorn had never existed outside imagination. Though this third explanation resembles the contemporary understanding of unicorns, all three explanations are based entirely on the European search for a European idea.” (Witelson 2023:6)

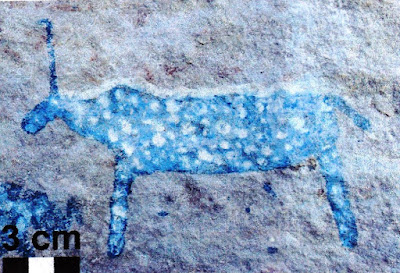

“Importantly, the perspectival argument was refuted over a century-and-a-half ago. The English traveler and artist Thomas Baines noted (correctly) that San images of two-horned animals invariably have two horns. Baines thus recognized that San images faithfully represent whatever the image-makers wanted to depict. Whatever perspectival ‘errors’ may be perceived, the painters ‘never fail to give each animal its proper complement of members.” (Witelson 2023:6) And, although many San animal portrayals might be thought to be cases of what Witelson calls ‘perspectival error’, he then presents us with some examples of this art that are decidedly one-horned.

One panel of lovely antelopes from a site southeast of Molteno has the necks and heads of two of the animals turned so that a second horn would be seen, and they are not.

And from a rock shelter south of Flaauwkraal in the Eastern Cape comes another panel of antelopes with their heads turned showing that they only possess one horn. These portrayals illustrate the San belief in unicorns as well as their artistic ability.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. Other photographic credits are as listed. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

PRIMARY REFERENCES:

Faris, Peter, 2018, The Paleolithic Unicorn – Found At Last?, 28 July 2018, Published online by https://rockartblog.blogspot.com.

Jackson, Justin, 2023, Chance cross-cultural unicorn concepts lost in translation, 16 March 2023, Phys.org News online. Accessed online 16 March 2023.

Witelson, David M., 2023, Revisiting the South African Unicorn: Rock Art, Natural History and Colonial Misunderstandings of Indigenous Realities, Published online by Cambridge University Press, 13 March 2023. Accessed online 16 March 2023.

SECONDARY REFERENCES:

Barrow, J., 1801, Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa in the Years 1797 and 1798, Volume 1, Cadell & Davies, London.

Stow, G.W. & Bleek, D., 1930. Rock Paintings in South Africa. London

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment