An important component of the rock art in the American Southwest represents images of shields and/or shield bearing warriors, but shields, as archeological artifacts from prehistoric times are very rare.

“Shields from across the Americas, whether of animal hide or basketry,

as objects made from perishable organic materials, are inherently

disadvantaged in terms of their archaeological visibility when compared

with more durable lithic, ceramic, and bone products.”

(Jolie 2022:3) Most shields in collections reflect the contact and

historic periods where collectors have been able to acquire them for

collections.

In 1978 Barton Wright wrote “Prehistoric shields have been excavated from burials at Mesa Verde, Aztec, and Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto. All of these shields are basketry. The coil of the basket is a bundle of three willow rods laced together with yucca in a simple, non-interlocking stitch to form a circular plaque roughly three feet in diameter. The center is bowed outward slightly to leave room for the hand behind a hardwood grip. The shield is supported by this short hand grip, lashed with yucca across the inner convexity. These wooden handles were recovered intact on the Mummy Cave and Aztec specimens which is an extremely rare occurrence. The Mummy Cave shield showed that the positioning of the handle had been changed at least once, possibly for better balance.” (Wright 1976:4)

A few discoveries of shields made by basketry techniques have turned up

in excavations in the American southwest. The techniques used in basketry

weaving in the Southwest are plaited and coiled basketry. Plaiting is the

criss-cross intertwining of the material used for things like mats. Coiled

basketry uses rods sewn together with a material. “All of the shields are essentially large shallow trays or plaques made

in close coiling by sewing non-interlocking stitches over a three whole

rod bunched foundation. Formal variability largely exists in terms of

their degree of concavity and overall diameter which, in most cases, due

to the presence of a rim or coil curvature, can be estimated with a high

level of certainty. Extant basketry shields range from about 50 to 88 cm

in diameter. These

measurements likely give us a rough indication of the size of basketry

or hide walking shields as being, on average, closer to 70+ cm. As noted

above, iconographic depictions of shields are known to be up to 90 cm in

diameter, but there is no reason to assume that any or all such

depictions were executed to scale. Work direction is uniformly

right-to-left (leftward) and work direction is always concave, resulting

in the painted, decorated surface being the convex surface. In general,

all of the shields reflect a technology and style wholly at home in the

northern southwest during the AD 1100s and 1200s, but for which thicker

foundation rods and stitching material (all likely Rhus sp.) were

employed to create a thicker, denser-walled basket compared to similar

contemporaneous coiled baskets of identical structure from the

Southwest.”

(Jolie 2022:13-14))

Gary David reported on the discovery of a basketry shield during excavations at Aztec Ruin. “In one of the rooms the bones of an obviously high-status man nicknamed “the Warrior” was found. Wrapped in a turkey-feather blanket, his skeleton measured 6’2” tall, making him at least a foot taller than the average height of males at that time. On top of his body was found a large woven-basketry shield measuring three feet in diameter. Placed on this warrior shield were several curved sticks (boomerangs).” (David:20) These were, of course, either rabbit sticks or fending sticks.

“The outer surface of the Aztec shield has been painted. The central portion is blue-green with a thin rim of red. The outer margin of the shield was covered with pitch and sprinkled with powdered selenite for sparkle. The Mummy Cave shield is also decorated. The central part is covered by a frog-like figure with an orange spot on its back and the rim is painted with a divided border of yellow and blue-grey. This is the same design that occurs on the canyon wall at Betatakin. The Mesa Verde shield was badly deteriorated and no longer retained a trace of its decoration; however, it had been constructed in the same fashion as the other two examples. These shields are from the Pueblo III period of the Anasazi people dating from A.D. 1100-1300.” (Wright 1976:4-6)

“Surprisingly, there are, in fact, a few traces of basketry shields being used in the historic period. A single extant Tohono O’odham basketry shield collected in 1884, some 49 cm in diameter, is fabricated in 3/3 twill strips of unidentified material with a burlap-like cloth covering painted black with a white floral-looking design surrounding a black center. A basketry shield is also reported for the San Juan Southern Paiute, and this is all the more noteworthy because of their residence in southern Utah/northern Arizona and the inferred influence of ancient Pueblo basketweaving traditions on their own.” (Jolie 2022:6)

Barton Wright (1976) did not believe that basketry shields would have had small efficacy once the bow and arrow were adopted. “It is extremely unlikely that these basketry shields would have deflected or stopped an arrow or lance. Since lances have never been found in archaeological context in the Southwest, they were probably not a factor in the use of a basketry shield. Native archers, on the other hand, who had little difficulty in penetrating the chain mail of the Spanish or the padded fiber armor of their mestizo warriors, would have had no difficulty in penetrating the half inch willow rods. Judd believed on the basis of his excavations that arrows, clubs and thrown rocks were the most common implements of warfare in the Southwest. It seems logical to assume that basketry shields were used for cushioning the fracturing blows of clubs or thrown rocks rather than defense against arrows.” (Wright 1976:6) As it turns out, however, basketry shields have been seen to be quite capable of stopping arrows. I suggest that Wright had forgotten that the flexibility (or “cushioning”) he writes about is an effective way of absorbing the energy of the arrow’s impact as Jolie’s discovery teaches us.

Forton disagreed with Wright, in his 2019 doctorial thesis he wrote: “Pueblo III shields were essentially coiled baskets worn on the arm and were crafted as a deterrent to the bow and arrow, which had made fending sticks obsolete. Imagery is confidently identified as depicting shields, based on physical examples excavated from Mesa Verde, Aztec Ruins, and Canyon del Muerto. The shield from Mesa Verde was too deteriorated to ascertain any designs it may have born, but the shield from the Aztec West great house was painted in concentric bands of green blue, while the Canyon del Muerto shield was painted with a froglike figure. Shields in Southwest rock art are frequently decorated with concentric circles and the Canyon del Muerto shield is similar in form to a striking shield pictograph at Betatakin.” (Forton 2019)

One basketry shield from White House in Canyon del Muerto calls into question Wright’s assertions of their ineffectiveness against the bow and arrow and confirms Forton’s statement. “Though missing its center, it is mostly complete and was at least about 74 cm in diameter originally. The convex surface exhibits a painted design in the form of a black and red checkerboard band some 20–25 cm wide that divides the basket in half. The convex surface exhibits multiple holes, some with penetrating remnants of hide thongs that suggest former pendant items and, most notably, the tips of two wooden projectiles embedded in its coils. A direct AMS radiocarbon determination on stitching fiber yielded a date of 817+/-35 rcy BP.” (Jolie 2022:17) In other words Jolie (2022) found the remains of a basketry shield with the tips of two arrows stuck in it. These are self arrows with pointed wooden tips and lacking arrowheads but, it is possible that given their smaller diameter they may have had a greater chance of penetration than a stone arrowhead.

“Sometime prior to AD 1200, coiled basketry shields may have supplanted fending sticks in response to bow and arrow use, and the newly available chronometrics on basketry shields reviewed here suggest the existence of conflict in the northern Southwest before the widely accepted social unrest of the AD 1200s. The possibility also remains that basketry shield production persisted at a low level into the historic era among some Southwestern groups. Accepting that shield imagery remains mute on construction technique, it seems prudent not to assume that all shields depicted are automatically hide.” (Jolie 2022:27) I am here suggesting that Jolie’s statement that “shield imagery remains mute on construction technique” is too negative, I believe that the many rock art images of anthropomorphs holding a spiral may be, in fact, representations of figures with basketry shields.

“Thus, visibility again looms large as a key dimension for understanding and evaluating the multiple roles of shields and shield imagery in the prehispanic Southwest. The basketry shields described above inhere with strong visual qualities that were arguably designed to impact viewers’ perception across multiple contexts. Although suffering from imperfect preservation that contributes to their archaeological invisibility, the very fact that three of the five known basketry shields originate from areas largely devoid of shield bearing imagery invites a renewed look at shield imagery and its distribution.” (Jolie 2022:27)

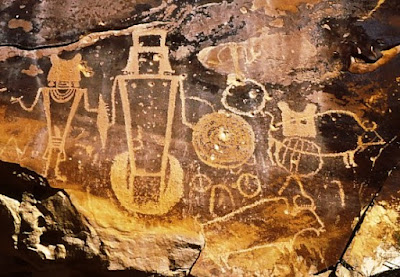

The famous 3-Kings panel at McConkey Ranch ouside of Vernal Utah shows a group of fremont figures, some of which are obviously armed warriors, with three spirals in the composition. One is in the lower right of the picture, one is next to the waist on the right side of the central figure, and the third is just above the shield being held by that central figure.

Joli wrote (2022): “Perhaps the most famous rock imagery (paintings, petroglyphs, and pictographs) shield depictions in the Southwest are those from Tsegi phase sites in the Kayenta region of southern Utah and northern Arizona dating between about AD 1250 and 1300. Numerous large-scale shields, some up to 90 cm in diameter, are executed in white, tan, purple, and pink clay mixtures and are found in or near alcoves and defensible cliff dwellings. Various interpretations of these and later shield images see them as symbolizing socioreligious or clan affiliations, community identity, or perhaps even marking the locations of particular clan or residence groups. Shield petroglyph images from Hopi have also been stated to be records of successful battles with adjacent groups (Wright 1976)." (Joli 2022:9-10) The opening line of this paragraph, of course, would only be true if the spirals associated with warriors in famous Fremont portrayals like the 3-Kings panel at McConkey Ranch, Vernal, Utah, are not meant to be examples of basketry shields.

The AD 1100s and 1200s time period cited by Jolie (2022: 13-14) also falls well within the dates (AD 1 to 1301) of the Fremont Culture which resided a little farther North centered on Utah and western Colorado. (Wikipedia) Fremont basketry is a distinctive one-rod-and-bundle technique that is “so unique that it has led some to suggest that the Fremont culture can be defined on the basis of this single artifact category alone.” (Madsen 1989:9) As Wright (1976:4) stated above “All of the shields are essentially large shallow trays or plaques made in close coiling by sewing non-interlocking stitches over a three whole rod bunched foundation.” This suggests that we have no extant examples of basketry shields by Fremont peoples, however the Fremont culture area also boasts extensive shield bearing warrior imagery. Interestingly, the Fremont region also boasts many petroglyphs of warriors holding spirals, which I am suggesting may represent basketry shields. Fremont artists also left numerous images of spirals by themselves which could represent shields as well.

Basketry shields, like most baskets in the American Southwest, were created by coiling where the weft of the basket is started in the center and coils horizontally, continuously being sewn to the previously completed element inside the coil. Given this coiled construction I suggest that many shield figures holding a coil (spiral) are meant to represent figures with basketry shields, not hide shields with spiral decoration. Instead of “ceremonial objects,” or hide shields painted with spiral decoration, or figures connected to the Sun, or water, or so many of the other explanations put forward over the years, I am suggesting that many of them are warriors holding basketry shields. Sometimes things actually are what they look like they are.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

David, Gary A., Giants, Kachinas, and Cannibals, https://www.academia.edu.

Forton, Maxwell M., 2019, Shields of the Tsegi: Pueblo III Social Affiliation as Seen in Spatial Patterning of Shield Iconography, PhD thesis, Dept. of Anthropology, Binghamton University, Academia. Accessed 29 October 2023.

Jolie, Edward, 2022, Basketry Shields of the Prehispanic Southwest, The Heard Museum, June 2022, KIVA, DOI:1080/00121940.2022.2086400.

Madsen, David B., 1989, Exploring the Fremont, Utah Museum of Natural History, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Wikipedia, Fremont Culture, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fremont_culture. Accessed online 9 September 2023.

Wright, Barton, 1976,

Pueblo Shields From the Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection, Northland Press, Flagstaff, AZ, © The Heard Museum, Phoenix,

Arizona.

No comments:

Post a Comment