One minor,

but enjoyable, facet of the study of rock art in the American Southwest is the

search for Mesoamerican influences in the imagery. Many examples of large-eyed

anthropomorphs, for instance, have been labeled (whether righly or wrongly) as

Tlaloc, the Aztec rain god. I have previously written about so-called abstract

examples of rock art that resemble glyphs in Mayan or Aztec writing. On 30

October 2021 I published “Symbols for

Geologic Phenomena in Rock Art – Earthquakes Revisited” (Faris 2021) in

which I showed a symbol in New Mexico that resembled the Aztec glyph

representing earthquakes. On 15 August 2015, I published “Wind Symbols in Rock Art of Chaco Canyon” showing a petroglyph in

Chaco Canyon that appears identical to Mesoamerican breath/speech/wind scrolls.

(Faris 2015) I make no claims to being a Mayanist, linguist, or epigrapher, so

these comparisons may be on shaky ground, but it is an interesting question.

Now, I am presenting another Mayan symbol that has possible relatives in the

American Southwest – the glyph for cacao.

Cacao, the flavoring ingredient of our modern chocolate was of huge importance to the Maya. “During the Classical Period of the Maya, from approximately 250 – 900 A.D., chocolate was a cornerstone of daily life. It was currency, a ritual ingredient, and a pleasurable drink. But until recently, the details of Maya life were fairly opaque, largely due to the destruction wrought by the conquering Spanish. In the 1980s, after intense effort by Mayanist scholars, there was breakthrough after breakthrough in deciphering Maya glyphs, the written symbols that survived in codices, stone carvings, and pottery. One milestone was the examination of a remarkable ancient vessel, which was found by an unlikely party, to contain chocolate.” (Ewbank 2019)

This vessel was found in an untouched Mayan tomb. “In 1984, archaeologists discovered a pristine Maya tomb in the Rio Azul region of Guatemala. Among the royal offerings, they found an exquisite pot. Topped with a twist-top and a handle painted like jaguar skin, it contained an intriguing residue.” (Ewbank 2019:1)

“The archaeologists and anthropologists working on the Rio Azul project mused over whom to send the residue to for analysis. ‘Okay, well, who knows the chemistry of chocolate really well?’ Stuart says with a chuckle. So, they called the number on the back of a Hershey’s bar and got in touch with W. Jeffrey Hurst, an analytical chemist at the Hershey Food Corporation Technical Center. The chocolate company had labs full of PhDs, where Hurst and chemist colleague Stanley M. Tarka tested the residue. Sure enough, says Stuart, ‘they ran the chemical signatures, and they were spot on.’ Hershey chemists found caffeine and theobromine in the residue. ‘The only plant or organic material in all of ancient America that can produce those two chemical signatures together are cacao.” (Ewbank 2019:2)

This pot also had a number of Mayan glyphs on the outside, and the excavators called in Mayanist David Stuart to decipher them. “’I was actually the person they brought on to read all of the hieroglyphs that they found in their excavations, which was a pretty cool job to have,’ Stuart says. While Stuart only saw photographs of the pot, he was nevertheless struck by it. ‘Wow, that is one bizarre vessel,’ he remembers thinking. Not only did it have an unusual shape, but the glyphs adorning it were remarkably well preserved. ‘and then it was like, Wait a minute, two of them spell out the word kakaw.’” (Ewbank 2019:2) Kakaw is the Mayan equivalent for our modern word cocoa, one of the few Mayan words that are also common in our modern English.

At Chaco Canyon in western New Mexico the archaeologists who excavated Pueblo Bonito found a large number of cylindrical pieces of pottery. “Scientists have long puzzled over the purpose of tall, cylindrical jars found in the northwestern New Mexico site known as Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. Speculations range from vessels for corn beer or, with skin stretched over the tops, for drums.” (Ehrenberg 2009)

Patricia Crown of the University of New Mexico “had learned of similarly sized jars from some Maya sites that researchers knew were specialty vessels for cacao drinks. (When the symbols on the Maya jars were finally deciphered, they read the equivalent of ‘This is Bill’s cacao vessel’) Crown sent shards from several jars and a pitcher to paper coauthor Jeffrey Hurst, a specialist in analysis of cacao remains with the Hershey Center for Health and Nutrition in Hershey, Pa.” (Ehrenberg 2009) This is the same scientist who had done the analysis for the Mayan pot from the Rio Azul site.

“Using mass spectrometry and high performance liquid chromatography, Hurst analyzed the traces of residue on the jar shards. Cacao has more than 500 compounds, but theobromine gives it away. The chemical could have only come from the cacao plant, a neotropical tree that doesn’t grow north of Mexico. Three of the five shards had traces of theobromine, the pitcher shards did not Crown says.” (Ehrenberg 2009) This analysis, then, seems to provide proof that Mexican cacao was present in the American Southwest.

Indeed, “this is not only evidence for cacao use north of the Mexican border, but, if these sherds are indeed from cylinder jars, it is evidence for how cylinder jars were used in rituals in Pueblo Bonito. At least on some occasions, the jars held a drink made from cacao seeds brought from a great distance.” (Crown and Hurst 2009: 2112)

“Pueblo groups and an ensuing Southwest society traded turquoise for Mesoamerican cacao for about five centuries, from around 900 to 1400, proposes a team led by archaeologist Dorothy Washburn of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Surprisingly, large numbers of people throughout Pueblo society apparently consumed cacao, from low-ranking farmers to elite residents of a multistory pueblo.” (Bower 2011)

“Whether Chacoan ritual practitioners appropriated and adapted the use of cacao and cylinder vessels to existing ritual in a way that was uniquely southwestern or adopted a Mesoamerican ritual remains and open question.” (Crown and Hurst 2009: 2112)

If cacao itself was present at Chaco Canyon it could only have been traded in from Mesoamerica, and with the physical presence of cacao, is it not conceivable that the Mayan symbol designating cacao could have come north with it? “Cacao: that is, chocolate. ‘It’s one of the few words we use that is actually Mayan,’ Stuart says. The Maya glyph for cacao, as it appears on the Rio Azul vessel, looks like a fish. But ‘it turns out the fish is a phonetic sign,’ Stuart says. He recognized that the glyph combining a fish (ka), a comb or fin (ka), and the sign for –w(a) was, of course, Kakaw. While Mayanist Floyd Lounsbury was the first to phonetically decipher a cacao glyph a decade prior, deciphering the cacao glyph on a Maya vase was a breakthrough.” (Ewbank 2019)

Fish variant of Mayan glyph for cocoa. Drawing by David Stuart. Internet illustration, public domain.

So the fish provides for the syllable KA, the fin provides another KA, and the small ear-like oval is the W, adding up to KAKAW or cacao.

Head variant of Mayan glyph for cocoa. Drawing by David Stuart. Internet illustration, public domain.

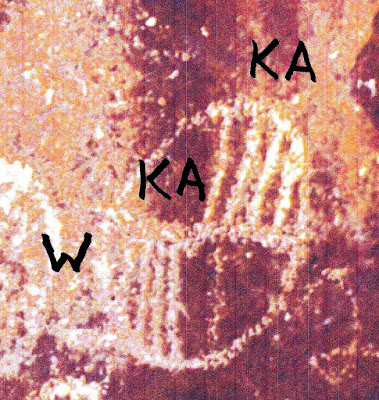

In another rendering of the glyph the fish is replaced with a head and two fins provide the KA and the KA, with an ear-like oval still providing the W. So. if we are going to find an equivalent to the Mayan Kakaw glyph in the American Southwest we should look for a pair of fin or comb like shapes with the ear-like oval. And I have indeed found at least a couple of examples that just might fill this bill.

My first possibility is found on Mesa Prieta in Rio Arriba County, New Mexico. Two fans or combs are contained in a circle with the oval ear-like oval appended to it, much like the second, or face variant, example of the Mayan glyph.

Taos county, San Luis Valley, northern New Mexico. Photograph Peter Faris, March 1995.Another possibility, although somewhat weaker, also has two fans or combs with an ear-like oval, but without the enclosing circle. This one is in the San Luis Valley, in Taos County in Northern New Mexico.

Were these meant to be references to cacao in northern New Mexico? I really do not know, but it is certainly fun to do the speculation.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Bower, Bruce, 2011, Pueblo trade for chocolate big-time, 17 March 2011, https://www.sciencenews.org, accessed 17 September 2022

Crown, Patricia L., and W. Jeffrey Hurst, 2009, Evidence of cacao use in the Prehispanic American Southwest, pp. 2110-2113, PNAS, 17 February 2009, Vol. 106, No. 7, www.pnas.org.

Ehrenberg, Rachel, 2009, Chocolate may have arrived early to U. S. Southwest, 2 February 2009, https://www.sciencenews.org, accessed 15 October 2022.

Ewbank, Anne, 2019, Archaeologists, Mayanists, and Hershey’s Collaborated to Reveal This Ancient Vessel’s Secrets, 21 February 2019, https://atlasobscura.com/articles/mayan-chocolate?, accessed 15 October 2022.

Faris, Peter, 2021, Symbols for Geologic Phenomena in Rock Art – Earthquakes Revisited, 30 October 2021, https://rockartblog.blogspot.com/2021/10/symbols-for-geologic-phenomena-in-rock.html

Faris, Peter, 2015, Wind Symbols in Rock Art of Chaco Canyon, 15 August 2015, https://rockartblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/wind-symbols-in-rock-art-of-chaco-canyon.html

No comments:

Post a Comment