I have written previously that in a society where items were individually handmade, the variations in personal items such as shields, headdresses, jewelry, etc., made those items identifiable with certain individuals, and that a representation of that in rock art might be considered a form of portraiture. In this column I will expand that idea to patterned, woven sandals. On 19 August 2017 I posted a column titled “Images of Footwear in Rock Art – Anasazi Sandals”, in which I discussed proposals that sandal prints in rock art might represent travel, or may have served a ceremonial purpose. In this column I will look at the idea that a representation of a patterned sandal print could have served to identify a particular individual, and that a representation of that print could be considered a form of portraiture.

Woven patterned sandals are unique to individual creators and/or users, and their contemporaries would recognize the pattern in footprints left on the ground. A representation of that patterned footprint pecked or painted onto a rock surface would also be recognizable to others in that group, and would thus serve as an identifier for a specific individual.

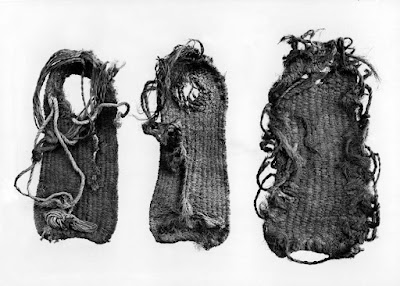

Donna Glowacki observed in 2015

that "Changes in sandal technology and the iconography depicted on

murals and in rock art imply widespread reorganization in Western Mesa Verde

influenced in part by changing relationships with and perceptions of Chaco and

Aztec that altered local interactions and practices. For example, twined

sandals, made of finely woven yucca with raised geometric designs on the tread

or designs that were painted or dyed after production were used until the early

1200s, subsequently being replaced by plaited sandals." (Glowacki

2015:140)

These are assumed to have been used as ceremonial dance footwear, given the amount of work, and the specialized knowledge, required to produce them "the intricacies of the unique geometric designs on the tread, and the impracticality of wearing finely twined sandals for daily use." (Glowacki 2015:140) If they were used as ceremonial wear by a certain individual, then a painted or pecked representation of that pattern could be intended as a reference to the ceremony, as well as that individual.

Benjamin Bellorado began to study twined

sandals in 2016, focusing on weaving technique and designs. By 2018 he had “analyzed almost 150 sandals from sites in

Chaco Canyon, the Aztec Community (a late Chaco colony), Mesa Verde National

Park, Canyon del Muerto, and the Bears Ears area.” (Bellorado 2018:39) He

found that patterns and techniques varied with location and that they could be

traced to certain sites.“Although no two

pairs are exactly alike, my preliminary analyses show patterns in wh ere people

were wearing certain kinds of twined sandals – in other words, sandals that

were made the same ways and with the same tread designs were often recovered

from the same sites. Moreover, in Chaco Canyon and in the Bears Ears area,

these sandals were recovered near sites or rooms that had depictions of similar

sandals with geometric tread patterns in building murals and rock art.” (Bellorado

2018:39-40)

Stephen Nash also recognized this. In 2018 he wrote “Ancient shoes not only protected the feet, they also sometimes acted as signaling devices. And given the level of investment in their manufacture, sandals and moccasins also may have served as style markers and status symbols, just as much footwear does today. How else do we explain today’s market for US$350 sneakers and US$1,000 pumps? Surely not improved performance or function. Stylistic differences may have useful functional corollaries, however. Have you ever gone hiking and seen the footprint of a hiker who came before you? In all likelihood, you noticed a boot print that may be unique to a manufacturer – but not to the wearer. In ancient times, you may have been able to use a footprint to identify the specific wearer. One of the many surprising things about ancient sandals is that they often had unique designs on their soles. They served as identification cards!” (Nash 2018:4)

So, now we have a number of possible meanings for pictograph or petroglyph panels that illustrate patterned sandal prints. They could, of course, still represent travel, or have ceremonial implications, and they would also convey identity of a specific individual. This can be expanded to suppose that they may represent that specific individual’s travel, or that specific individual’s ceremonial participation, as well as just identifying the specific individual, but, I believe, that the identification of a specific individual is a major purpose, whether or not there are sub-implications in such portrayals. So, again I argue, that a patterned sandal print would be the equivalent of a portrait, or a signature - it prompted one’s contemporaries to think of that one, specific individual. Perhaps an ancient “Killroy was here.”

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on this subject you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Bellorado,

Benjamin A., 2018, Sandals

and Sandal Symbolism in Greater Bears Ears and Beyond, Archaeology

Southwest Magazine, Fall 2017 and Winter 2018 issue, 39-41.

Faris,

Peter, 2017, Images of

Footwear in Rock Art – Anasazi Sandals, 19 August 2017,

www.rockartblog.blogspot.com

Glowacki, Donna M.,2015 Living

and Leaving, A Social History of Regional Depopulation in Thirteenth-Century

Mesa Verde, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Nash,

Stephen E., 2018, Why Are

Some Caves Full of Shoes?, 1 August 2018, https://www.sapiens.org/column/curiosities/ancient-shoes/,

accessed 12 January 2021.

%20in%20present-day%20New%20Mexico.%20Stephen%20E.%20Nash.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment