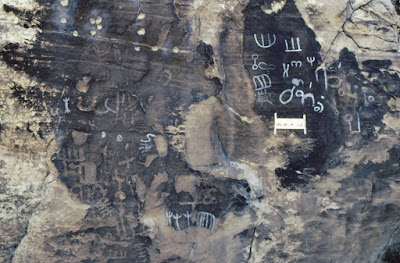

Petroglyphs across from Munsell

Site, Buffalo arroyo, Pueblo

County, Colorado.

Photograph Peter Faris, Oct. 1998.

It is

called Diffusionism, the argument that travelers from the Old World visited the

New World over and over in prehistoric periods. Various proponents make their

cases for visits by Phoenicians, Celts, even the Chinese in the centuries

before Columbus. We now know that Vikings actually did make it to North America

so arguments about American runestones have received new fuel for their fires,

but here I am going to visit the question of abstract symbol petroglyphs in

Southeast Colorado and the clinging question of whether or not they were

created by visiting Phoenicians.

Near Bear rock, panel 3,

Purgatoire Canyon, southeast

Colorado, Photograph Bill

McGlone, date unknown.

This

question first gained a measure of prominence in the nonsense of Barry Fell and

his so-called epigraphic translations. Given that as an origin, these

Diffusionist theories were all too easy for archaeologists to discount and

decry. There have, however, been some serious researchers who were at least

willing to consider the possibilities. For southeast Colorado these researchers

were Bill McGlone and Phillip Leonard who first became interested in some

inscriptions that they thought might represent Celtic Ogam. Although their

focus changed within a few years from Ogam to proto-Sinaitic inscriptions this

investigation was forever tainted by the Ogam connection. Bill McGlone later admitted to me that he regretted that he had ever gotten involved with the Ogam controversy because of that fact, and

his trouble getting actual experts in epigraphy to even pay attention.

Farrington Springs, southeast

Colorado. Photograph Bill McGlone,

Oct. 1988. (trident is supposedly

dated to 1975±200 BP

by cation-ratio dating).

The basic

problem came down to this - what evidence is there that these inscriptions can actually be

in proto-Sinaitic? Opponents, with traditional archeological

investigations in mind, say that there is absolutely no evidence at all, a

total lack of corroborative evidence, while proponents say the inscriptions

themselves are corroborative evidence. Now, I am in no way an epigrapher,

linguist, or even an expert on the Middle East, so I have to look at the

question another way entirely. In his 2018 "A

Study of Southwestern Archaeology" Stephen Lekson raised the question

of applying legal standards of evaluation to questions that provide problems

for traditional scientific analysis. Lekson adapted an argument by Charles

Weiss, a retired professor from Georgetown University, for use in this attempt,

and since it was good enough for him it is certainly more than good enough for

me. Weiss's scale from 1 to 10 ranges from 0% probability (impossible) to 100%

probability (beyond any doubt), and uses courtroom terms like "probable cause",

"preponderance of the evidence, and "beyond a reasonable doubt"

to evaluate the likelihood of arguments. (I will not take the time and space to

put in Weiss's whole table, for those who are interested I will refer you to

his publication listed below in references)

Four-Mile Ditch site, southeast

Colorado. Photograph Bill

McGlone, Nov. 1990.

So in order

to evaluate this I believe that it comes down to two basic questions; what is

the likelihood that Phoenicians or other peoples from the Middle East actually

were here to create the inscriptions, and if not proto-Sinaitic inscriptions

what else could they reasonably be? I will address these in order.

Mustang site, southeast

Colorado. Photograph Bill

McGlone, August 1989.

The total

straight line distance from the coast of Israel to southeastern Colorado is in

the order of 6,700 miles. Of course, to sail that it would not be in a straight

line so the actual figure has to be considerably higher. A Phoenician ship

would have to leave the coast of Israel, sail through the Mediterranean and out

the Pillars of Hercules, cross the Atlantic to locate the mouth of the

Mississippi River. Then it's a simple 350 miles up the Mississippi to the

Arkansas River and about 850 miles up the Arkansas River to southeast Colorado,

and did I mention that much of the Arkansas is not really navigable?

Purgatory Canyon, south of the

bear, Bent County, Colorado.

Photograph Peter Faris, June 1991,

(trident symbol cation-ratio dated

1,975 plus or minus 200 BP.)

Chart of Proto-Sinaitic and

Early Phoenician characters.

http://www.ancientscripts

comprotosinaitic.html

Then there

is the problem that these symbols were not created with metal tools which our

hypothetical Phoenician travelers certainly had. Also, although some of the

characters resemble some proto-Sinaitic letters, there are others that do not,

so what about the poor matches, other symbols and wrong characters? This

argument is usually explained away by attributing the inscriptions to some poor

Phoenician crewman who is barely literate, if at all. However, if it was

important enough to take this 8,000+ mile journey to leave the inscription in

the first place why would not the captain of the ship or someone in charge who

is fully literate be the one to write it, and why would he pound it in with a

rock instead of their metal tools? This is then sometimes countered with the

proposal that the inscriptions were actually made by Native Americans in

imitation of real proto-Sinaitic writing, sort of a prehistoric North American

cargo-cult argument. My only answer to this is to ask where is the real

inscription that the Native Americans were attempting to copy or imitate?

Nothing of that sort has ever been found. Using the legal argument evaluation I

have to find that the preponderance of evidence is against these markings being

proto-Sinaitic script "beyond reasonable doubt" (67% to 99% on

Weiss's scales), and that the argument against this is substantially proven.

Near Bear Rock, Purgatoire

Canyon, southeast Colorado.

Photograph Bill McGlone,

photo undated.

So, if not

proto-Sinaitic (or some other north African) script, what are they. My answer

of choice is that most of them are probably random doodles. Some of them are

undoubtedly simple symbols representing other things like a circle for a sun,

etc. But why are they there lined up like inscriptions? I would answer that

like attracts like. We have learned this from modern taggers as well as from

the people who vandalize rock art sites. Why do they pick the rock art panel to

vandalize, why not make their marks away from the rock art? If I make a mark in

a location, someone else is likely to pick that spot for their own mark. The

other point that I think applies here is that there are actually only a limited

number of simple geometric symbols that you can make with curved and straight

lines. Doodles us them, simple pictographs use them, abstract images use them,

and written scripts use them. Of course they resemble writing, they are made up

of the same curved and straight elements as written script, but they carry no

written message. And, lined up like written inscriptions? Standing on the

ground and facing the cliff there is a limited vertical space which is

convenient for me to work in, in other words, my images would probably be generally

arranged more horizontally than vertically. (Some of these inscriptions are too

high on the cliff to be reached today without a ladder. I assume that this

might be a sign of erosion of the valley bottom since their creation.)

Split Mesa panel, southeast

Colorado, Photograph Bill

McGlone, photograph undated.

Now using

the same legal analogy for evaluating this I would say that the definition of

these marks as doodles and abstract, instead of being written characters, has

been proven to a standard of "reasonable belief" (again 67% to 99% on

Weiss's scales) and that the likelihood that they represent a proto-Sinaitic

script is thus between 1% and 33%. If these points were being argued in a court

of law it would be found that they are not written inscriptions. Not

scientifically proven, of course, but logically established nevertheless.

In closing

I want to say that in spite of Barry Fell's inaccuracies and sloppy

interpretations, some of the people who believe in the diffusion theory, who

believe that these inscriptions are actual and real proto-Sinaitic writing, are

educated and intelligent. As in all cases of attempted interpretation without

actual physical evidence, in the end it falls to belief to define your answer.

You either believe it or you don't, and I don't.

NOTE:

For a current

presentation of the diffusionist position on proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in

Colorado you should read Carl Lehrburger's

writing listed below in references.

NOTE 2: Yes, the images have been colored in on the rock. Early epigraphy researchers in southeast Colorado seem to have used aluminum paint to make them more readable and photographable.

NOTE 3: Some

images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for

public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public

domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner

will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should

read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Lehrburger,

Carl

2015 Secrets

of Ancient America: Archaeoastronomy and the Legacy of the Phoenicians, Celts,

and Other Forgotten Explorers, Bear & Company, Rochester, VT.

Lekson,

Stephen H.

2018 A Study

of Southwestern Archaeology, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City

Weiss,

Charles

2003 Scientific Uncertainty and Science-Based

Precaution, article in International

Environmental Agreements, June 2003, DOI:10.1023/A:1024847807590

No comments:

Post a Comment