Saturday, May 30, 2020

(MIS)APPROPRIATION - KOKOPELLI:

Flute player, Mesa Prieta,

Rio Arriba county, New Mexico

Photo Peter Faris, 1997

The concept

of (mis)appropriation is basically the adoption of one aspect of a particular

group or culture by another group or culture and using it in ways that the

first group or culture never intended, or finds offensive. On March 3rd, 2012,

I posted a column titled Kokopelli,

in which I wrote: "Our culture has

enthusiastically adopted Kokopelli with the predictable results. We have

multiplied sillier and sillier Kokopellis, riding bicycles, skiing, playing

trombones, etc. I own a few myself given to me as gifts by friends. This may be

an inevitable part of our society’s attempt to accommodate, understand, and

appreciate another culture, but we should not allow this aspect of the modern

Kokopelli to make us forget the powerful attributes of fertility and blood

which he presented to the people who first conceived of him, and that he

represents a sacred image to many of our fellow citizens." (Faris

2012) To this list of misuses I would

now add puerile Kokopelli pornography.

Flute player, Mesa Prieta,

Rio Arriba county, New Mexico,

Photo Peter Faris, 1997

As to the

origins of the figure that we call Kokopelli - "Exactly when they first appear is uncertain, but nonphallic

fluteplayers without humps are present in Basketmaker III rock art dating back

to around A.D. 500. After A.D. 1000 they are present with hump and flute in

Anasazi rock art, pottery, and wall paintings. They also appear on ceramics of

the Mimbres in southern New Mexico around A.D. 1000 to A.D. 1150 and on Hohokam pottery by A.D.

750 to A.D.850" (Slifer and Duffield 1994: 4)

Kneeling flute player, Mancos canyon,

Montezuma county, New Mexico,

Photo Peter Faris, 1983

I suspect

that our use of the Kokopelli image may be as offensive to many Native

Americans of the southwest as the image of Andres Serrano's 1987 photograph of

a crucifix in a bottle of urine which he titled "Piss Christ" is to many devout Christians. That one

raised an uproar. We understand, and share to some extent, the horror that this

object presented to devout Christian evangelicals, but that empathy seems to

not translate well to the beliefs of other cultures, perhaps because we are so

sure that our beliefs are correct and therefore the beliefs of other cultures

are wrong. Remember the handful of occasions in recent years involving

cartoonists who drew images of the prophet Muhammad in a terrorism context, and

received death sentences in fatwas from Muslim clerics who deemed their

cartoons disrespectful to Islam. We take a political cartoon as free speech

guaranteed by our constitution, those Muslim clerics did not necessarily see

that as a right.

"A fatwa is any religious

decision made by a mufti (Islamic scholar who is an interpreter or expounder of

Islamic law). The most infamous fatwa is the one by Ruhollah Khomeini

sentencing Salman Rushdie (Muslim Essayist) to death - that's why most Western

people see fatwa just as a death sentence, although it's more than that." (Shuravi 2006)

My particular favorite

flute player, Long House,

Bandelier National Monument,

Los Alamos County, New Mexico,

Photo Peter Faris, Sept. 1985

In his 2018 book Petroglyphs,

Pictographs, and Projections: Native American Rock Art in the Contemporary

Cultural Landscape, Richard

A. Rogers addressed the question of misrepresenting and misappropriating one

culture's idea/image/icon by another culture. One point that Rogers makes

repeatedly, if I understand his position, is that flute-players and Kokopelli

are not at all the same thing, but a conflation which we, the outsiders, have

made of characters in the Hopi pantheon. "The

conflation of flute player images with Kookopölö, creating a situation where

all variations of the former are widely referred to as "kokopelli,"

is of concern to many Hopis, especially members of the flute clan. The

possibility remains, however, that some flute player images in rock art could

be related to Kookopölö. Church also quotes Clay Hamilton of the Hopi Cultural

Preservation Office as saying that flute player-like images without a flute but

carrying a walking stick or staff may indeed be Kookopölö." (Rogers

2018:180)

Kokopolo, p. 18, Alph H. Secakuku,

Hopi Kachina Tradition, 1995,

Northland Publishing,

Flagstaff, Arizona.

According

to Slifer and Duffield "There are

rock art depictions of fluteplayers without the hump or phallus, and there are

hump-backed, phallic figures with no flute. They may all be variations on the

same theme, but the flute seems to be the most common diagnostic element."

(Slifer and Duffield 1994:19) Indeed, as I wrote in The Day I Met Kokopelli, the Kookopölö of the Hopi is the

Assassin-fly kachina and the long proboscis is not actually a flute at all

(Faris 2012)

Crouching flute player, Mancos canyon,

Montezuma county, New Mexico,

Photo Peter Faris, 1983.

In this

column I am limiting my discussion to the figure that we call Kokopelli,

although there are certainly many other symbols that we have (mis)appropriated

in the same way. What drives out fascination with this figure, accurate or not,

whether authentic or a figment of our own imaginations? "Why are non-Native peoples drawn to indigenous rock art and/or

rock art imagery?What is its appeal? In what contexts (environmental, social,

political, economic) is rock art imagery reproduced, consumed, and discussed?

What structures of meaning inform, mediate, constrain, and enable the

interpretation and valuation of rock art? What are the ethical and ideological

issues involved in the appropriation of rock art imagery? What structures of

meaning inform the preservation or rock art sites? In all these activities, what/whose

interests are being served?" (Rogers 2018:8)

I cannot

yet answer all of these questions for myself, but, in general, to answer Rogers

I guess I have to say that it is my interests that are being served by my

fascination with this remarkable area of art history.

"The interpretation of ancient,

indigenous rock art by contemporary Westerners provides a clear case to

demonstrate the contrast. From a transmissional view, the meaning of much rock

art is lost due to the lack of a shared cultural context for assigning meaning

to the symbols. Possibilities for communication failure loom large: without

contextual (cultural) information, we are left, at best, with guesses as to the

literal referents of some images and almost entirely acontextual (outsider)

efforts to "crack the code" of the meaning of the images." (Rogers 2018:21)

I have long

maintained that there is no single meaning to any image. Yes, there was the

idea that its creator intended to portray, but there was also probably a

spectrum of imperfect understandings of that particular idea among his or her

contemporaries. Then, there are all of the imperfect interpretations of the

image by people who came after (usually from different cultures). Finally, we

come to whatever the result of our analysis is as to its meaning, and don't

forget as our culture evolves our descendents will probably change that

interpretation as well. Our interpretation in many instances says more about

ourselves and our culture as it does about the rock art itself.

"The interaction with rock art

may in many cases do little to truly understand the intentions of their ancient

creators, but that does not mean those contemporary meanings should be

dismissed as insignificant - instead, they offer insights into the interpreting

culture and their relationships with cultural others, be they ancient or

living. The question becomes not "are these interpretations correct (the

same as the originating culture)?" but instead "how did these interpretations

come to be (what are their conditions of possibility)?" and "what

kinds of identities, relationships, and social systems are being created

through these interpretations."

(Rogers 2018:22)

A few of the Kokopellis

gifted to the Faris household

over the years.

Given all

of this, as I confessed in my opening, I have a number of these examples of

Kokopelli in my possession. A sheet metal cutout mounted on our front door and

another on the garden fence, a couple of wall switch-plates, a candle stick,

and even a Christmas tree ornament, that were given to me as gifts over the

years (and believe me I do see the irony in having a Kokopelli hanging on our

Christmas tree). According to Rogers "indeed

Kokopelli - not the flute player and not Kookopölö, but the contemporary

commercial figure - is a hybrid creation, a piece of postmodern pastiche, not

in itself a 'real' or 'genuine' figure from any ancient culture."(Rogers

2018:326)

Perhaps

this all represents an example of most of our culture misunderstanding, and

therefore not respecting, this belief of the Puebloan peoples, and of the rest

of us blindly trying to evaluate the meaning of rock art scientifically, and

forgetting its emotional content.

NOTE: It has not been my intention in this particular posting to join

in the controversy about assigning Kookopölö/Kokopelli/Flute-player identities and

definitions. Those interested in trying to pin that question down should refer

to Slifer and Duffield's book listed below.

Those

interested in questions of cultural appropriation and misuse should consult

Richard Roger's excellent book listed below.

And

finally, some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a

search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended

to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits

if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports

you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Faris,

Peter

2012 Kokopelli,

March 3, 2012,

https://rockartblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/kokopelli.html

2012 The Day I

Met Kokopelli,

https://rockartblog.blogspot.com/2012/04/day-i-met-kokopelli.html

Rogers,

Richard A.

2018 Petroglyphs,

Pictographs, and Projections: Native American Rock Art in the Contemporary

Cultural Landscape, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Shuravi,

2006 Fatwa,

December 19, 2006, Urban Dictionary,

https://www.urbandictionary.com/defing.php?term=fatwa

Slifer,

Dennis and James Duffield

1994 Kokopelli:

Flute Player Images In Rock Art, Ancient City Press, Santa Fe.

Labels:

appropriation,

Kokopelli,

petroglyphs,

rock art

Saturday, May 23, 2020

EPIGRAPHY - ARE THERE PROTO-SINAITIC INSCRIPTIONS IN COLORADO?

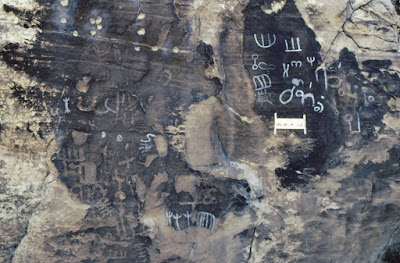

Petroglyphs across from Munsell

Site, Buffalo arroyo, Pueblo

County, Colorado.

Photograph Peter Faris, Oct. 1998.

It is

called Diffusionism, the argument that travelers from the Old World visited the

New World over and over in prehistoric periods. Various proponents make their

cases for visits by Phoenicians, Celts, even the Chinese in the centuries

before Columbus. We now know that Vikings actually did make it to North America

so arguments about American runestones have received new fuel for their fires,

but here I am going to visit the question of abstract symbol petroglyphs in

Southeast Colorado and the clinging question of whether or not they were

created by visiting Phoenicians.

Near Bear rock, panel 3,

Purgatoire Canyon, southeast

Colorado, Photograph Bill

McGlone, date unknown.

This

question first gained a measure of prominence in the nonsense of Barry Fell and

his so-called epigraphic translations. Given that as an origin, these

Diffusionist theories were all too easy for archaeologists to discount and

decry. There have, however, been some serious researchers who were at least

willing to consider the possibilities. For southeast Colorado these researchers

were Bill McGlone and Phillip Leonard who first became interested in some

inscriptions that they thought might represent Celtic Ogam. Although their

focus changed within a few years from Ogam to proto-Sinaitic inscriptions this

investigation was forever tainted by the Ogam connection. Bill McGlone later admitted to me that he regretted that he had ever gotten involved with the Ogam controversy because of that fact, and

his trouble getting actual experts in epigraphy to even pay attention.

Farrington Springs, southeast

Colorado. Photograph Bill McGlone,

Oct. 1988. (trident is supposedly

dated to 1975±200 BP

by cation-ratio dating).

The basic

problem came down to this - what evidence is there that these inscriptions can actually be

in proto-Sinaitic? Opponents, with traditional archeological

investigations in mind, say that there is absolutely no evidence at all, a

total lack of corroborative evidence, while proponents say the inscriptions

themselves are corroborative evidence. Now, I am in no way an epigrapher,

linguist, or even an expert on the Middle East, so I have to look at the

question another way entirely. In his 2018 "A

Study of Southwestern Archaeology" Stephen Lekson raised the question

of applying legal standards of evaluation to questions that provide problems

for traditional scientific analysis. Lekson adapted an argument by Charles

Weiss, a retired professor from Georgetown University, for use in this attempt,

and since it was good enough for him it is certainly more than good enough for

me. Weiss's scale from 1 to 10 ranges from 0% probability (impossible) to 100%

probability (beyond any doubt), and uses courtroom terms like "probable cause",

"preponderance of the evidence, and "beyond a reasonable doubt"

to evaluate the likelihood of arguments. (I will not take the time and space to

put in Weiss's whole table, for those who are interested I will refer you to

his publication listed below in references)

Four-Mile Ditch site, southeast

Colorado. Photograph Bill

McGlone, Nov. 1990.

So in order

to evaluate this I believe that it comes down to two basic questions; what is

the likelihood that Phoenicians or other peoples from the Middle East actually

were here to create the inscriptions, and if not proto-Sinaitic inscriptions

what else could they reasonably be? I will address these in order.

The total straight line distance from the coast of Israel to southeastern Colorado is in the order of 6,700 miles. Of course, to sail that it would not be in a straight line so the actual figure has to be considerably higher. A Phoenician ship would have to leave the coast of Israel, sail through the Mediterranean and out the Pillars of Hercules, cross the Atlantic to locate the mouth of the Mississippi River. Then it's a simple 350 miles up the Mississippi to the Arkansas River and about 850 miles up the Arkansas River to southeast Colorado, and did I mention that much of the Arkansas is not really navigable?

Purgatory Canyon, south of the

bear, Bent County, Colorado.

Photograph Peter Faris, June 1991,

(trident symbol cation-ratio dated

1,975 plus or minus 200 BP.)

Chart of Proto-Sinaitic and

Early Phoenician characters.

http://www.ancientscripts

comprotosinaitic.html

Then there

is the problem that these symbols were not created with metal tools which our

hypothetical Phoenician travelers certainly had. Also, although some of the

characters resemble some proto-Sinaitic letters, there are others that do not,

so what about the poor matches, other symbols and wrong characters? This

argument is usually explained away by attributing the inscriptions to some poor

Phoenician crewman who is barely literate, if at all. However, if it was

important enough to take this 8,000+ mile journey to leave the inscription in

the first place why would not the captain of the ship or someone in charge who

is fully literate be the one to write it, and why would he pound it in with a

rock instead of their metal tools? This is then sometimes countered with the

proposal that the inscriptions were actually made by Native Americans in

imitation of real proto-Sinaitic writing, sort of a prehistoric North American

cargo-cult argument. My only answer to this is to ask where is the real

inscription that the Native Americans were attempting to copy or imitate?

Nothing of that sort has ever been found. Using the legal argument evaluation I

have to find that the preponderance of evidence is against these markings being

proto-Sinaitic script "beyond reasonable doubt" (67% to 99% on

Weiss's scales), and that the argument against this is substantially proven.

So, if not

proto-Sinaitic (or some other north African) script, what are they. My answer

of choice is that most of them are probably random doodles. Some of them are

undoubtedly simple symbols representing other things like a circle for a sun,

etc. But why are they there lined up like inscriptions? I would answer that

like attracts like. We have learned this from modern taggers as well as from

the people who vandalize rock art sites. Why do they pick the rock art panel to

vandalize, why not make their marks away from the rock art? If I make a mark in

a location, someone else is likely to pick that spot for their own mark. The

other point that I think applies here is that there are actually only a limited

number of simple geometric symbols that you can make with curved and straight

lines. Doodles us them, simple pictographs use them, abstract images use them,

and written scripts use them. Of course they resemble writing, they are made up

of the same curved and straight elements as written script, but they carry no

written message. And, lined up like written inscriptions? Standing on the

ground and facing the cliff there is a limited vertical space which is

convenient for me to work in, in other words, my images would probably be generally

arranged more horizontally than vertically. (Some of these inscriptions are too

high on the cliff to be reached today without a ladder. I assume that this

might be a sign of erosion of the valley bottom since their creation.)

Now using

the same legal analogy for evaluating this I would say that the definition of

these marks as doodles and abstract, instead of being written characters, has

been proven to a standard of "reasonable belief" (again 67% to 99% on

Weiss's scales) and that the likelihood that they represent a proto-Sinaitic

script is thus between 1% and 33%. If these points were being argued in a court

of law it would be found that they are not written inscriptions. Not

scientifically proven, of course, but logically established nevertheless.

In closing

I want to say that in spite of Barry Fell's inaccuracies and sloppy

interpretations, some of the people who believe in the diffusion theory, who

believe that these inscriptions are actual and real proto-Sinaitic writing, are

educated and intelligent. As in all cases of attempted interpretation without

actual physical evidence, in the end it falls to belief to define your answer.

You either believe it or you don't, and I don't.

NOTE:

For a current

presentation of the diffusionist position on proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in

Colorado you should read Carl Lehrburger's

writing listed below in references.

NOTE 2: Yes, the images have been colored in on the rock. Early epigraphy researchers in southeast Colorado seem to have used aluminum paint to make them more readable and photographable.

NOTE 3: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

NOTE 3: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Lehrburger,

Carl

2015 Secrets

of Ancient America: Archaeoastronomy and the Legacy of the Phoenicians, Celts,

and Other Forgotten Explorers, Bear & Company, Rochester, VT.

Lekson,

Stephen H.

2018 A Study

of Southwestern Archaeology, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City

Weiss,

Charles

2003 Scientific Uncertainty and Science-Based

Precaution, article in International

Environmental Agreements, June 2003, DOI:10.1023/A:1024847807590

Labels:

Bill McGlone,

epigraphy,

petroglyphs,

Phoenician,

proto-sinaitic,

rock art

Saturday, May 16, 2020

AN EXAMPLE OF ROCK ART FORGERY:

Main panel on rear wall

of GvJm16, Photograph

Stanley Ambrose.

I have run

across a report of a whole new category of rock art vandalism. Counterfeit rock

art produced for Hollywood productions and left behind in the landscape when

the filming is over. It is perhaps best described by quoting from the abstract

of the paper itself.

Left side of main panel on

rear wall of GvJm16,

Photograph Stanley Ambrose.

Right side of main panel on

rear wall of GvJm16,

Photograph Stanley Ambrose.

"A large rock shelter at

Lukenya Hill, Kenya, is well known for its diverse and well-preserved

prehistoric paintings. Images recorded in the 1970s include geometric motifs

resembling those at sites in the Lake Victoria region, overlain by recent

paintings attributed to the Masai. Several new images of animals and humans

appeared between 1988 and 1995 that resemble those from central Tanzania, and

many preexisting images were obscured. If these new paintings had not been recognized

as modern forgeries they could have been used as evidence for a dramatic

revision of the prehistory and geographical distribution of the

Khoisan-speaking peoples and their belief system. The apparent motivation for

painting these new images was to serve as the background for a scene for the

Young Indiana Jones television series. In order to prevent future damage to

rock art sites and other significant cultural and natural heritage resources,

the film and tourism industries should be trained and certified to recognize

and avoid damaging such localities." (Ambrose 2007:1)

Faded images of a herd of

antelope, middle right of

GvJm16 main panel.

Photograph Stanley Ambrose.

Faded images of a large and

a small antelope, far right of

GvJm16 main panel,

Photograph Stanley Ambrose.

In other

words, if this is not readily clear, the scenery people for this television

series, in preparing the site to shoot a particular scene, had painted new and

counterfeit rock art over pre-existing real rock art, a shocking example of

cultural and scientific disregard.

White dotted giraffe and

streaky anthropomorph, not

present before 1988, GvJm16.

Photograph Stanley Ambrose.

Kongoni (hartebeest) painted in

yellow w/black barred face on

lower far right of main panel at

GvJm16, not present before 1988.

Photograph Stanly Ambrose.

"The damage inflicted of the

painted panel at GvJm16 during the production of the Young Indiana Jones

television program is not an isolated incident. A paleontological site at

Olorgesailie was used for a military battlefield scene for the Young Indiana

Jones series in the 1990s. Several other archaeological, paleontological and

geological localities have been altered and damaged during film productions.

Forged rock paintings remain on the walls of a lave tube cave on Mt. Suswa. An

open-air Neolithic site at Lukenya Hill (GvJm48)was bulldozed to provide a

level surface for a trailer for a movie set in the 1980s." (Ambrose 2007:5) And the author

documented a number of other like outrages.

Yellow feline with white outline on

lower far right of main panel at

GvJm16, not present before 198

Photograph Stanley Ambrose, 1995.

One

motivation in some instances was seemingly to provide more rock art to attract

tourists. This suggests that our own passion for rock art is partly to blame

for its vandalism. The other main motivation seems to have also been financial,

in order to attract the fees for film and television productions. But, at a

time when our own government has stripped Bear's Ears monument in Southern Utah

of some 80% of its land area to open it up to commercial exploitation it is not

quite the time for us to point the finger at this behavior.

"Although there are

well-established laws for the protection of such cultural and natural heritage

resources in Kenya, most transgressions are by individuals who have neither the

training to recognize cultural, archaeological, paleontological and geological

sites nor an understanding of their significance and responsible

stewardship."

(Ambrose 2007:131)

So, once

again, ignorance and venality have proven more powerful than cultural

sensitivity and the appreciation of creativity, and, as always, once it is lost

it cannot be wholly regained.

NOTE:

Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for

public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public

domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner

will contact me with them. For further information on this report you should

read the original report listed below.

REFERENCES:

Ambrose,

Stanley H.

2007 Raiders

of the Lost Art: Implications of Rock Art Forgery at Lukenya Hill, Kenya, for

Cultural and Natural Heritage Protection Strategies, in Deacon, J., editor,

The Future of Africa's Past: Proceedings of Rock Art Conference, 2004, Nairobi,

Trust for African Rock Art, Nairobi, pp. 128-132.

Labels:

Africa,

forgery,

pictographs,

rock art,

vandalism

Saturday, May 9, 2020

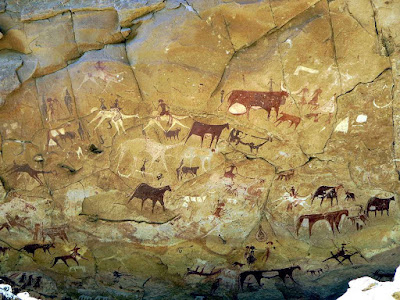

CATTLE IN AFRICAN ROCK ART:

Cattle. Photograph TARA

(Trust for African Rock Art)

Pretty

much anywhere you find rock art one of its most important themes is going to be

involved with primary sources of food for the indigenous population. This is

why there are so many horses and reindeer illustrated in the painted caves of

Europe, and so many bison in the rock art of North America. In Africa, the San

people (so-called Bushmen) illustrated their most sought after game animals,

especially eland but also giraffes and others. However, in the tribal cultures

of Africa the predominate animal in their rock art has been cattle images.

"Crying cows" of Algeria.

Photographs TARA.

"Archaeological

and genetic evidence suggests that domestication of cattle occurred 10,000 BP

in Western Asia. After this migrations of humans and cattle about 8,000 years

BP occurred followed by interbreeding with wild cattle in Northern Africa to

produce breeds local to the continent. More than 60% of the rock art of the

Sahara depicts cattle or cattle related activities reflecting the importance of

these events. All around Africa however, cattle depictions in rock art

abound." (TARA 2016:1)

African cow petroglyph.

Photograph after Noguera.

Red painted African cattle with herders.

Internet photograph - public domain.

I

assume that originally these people lived a classical pastoral lifestyle,

relying on their herds for food and resources. In a recent paper published in

the Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences a team consisting of Katherine M. Grillo, assistant professor

of anthropology at University of Florida, Fiona Marshall of Washington

University, and Julie Dunne (who led the study) at the University of Bristol

looked for traces of milk consumption on ancient pottery to confirm that the

cultures relied on this food resource. "After

excavating pottery at sites throughout east Africa, team members analyzed

organic lipid residues left in the pottery and were able to see evidence of

milk, meat and plant processing. 'This is the first direct evidence we've ever

had for milk or plant processing by ancient pastoralist societies in eastern

Africa,' Grillo said. 'The milk traces in ancient posts confirms the story that

bones have been telling us about how pastoralists lived in eastern Africa 5,000

to 3,000 years ago - an area still famous for cattle herding and the historic

way of life of people such as Maasai and Turkana,' Marshall said."

(Heritage Daily 2020)

African cattle petroglyphs.

Internet photographs - public domain.

But

the role of cattle in these societies goes way beyond the role of mere

foodstuffs. Perhaps inevitably, the herds became not only signs of wealth but

acquired spiritual value because of that importance. "Today many people see cows (and the consumption thereof) either

as a contributor to environmental destruction, or as a solution to feeding the

world's population. Both views are centered on the (important) role that cows

play in providing food primarily in the form of milk and meat. But cattle are

more than that. Through millennia and in different places in Africa, cattle

have been imbued with significant symbolic and social meanings in addition to

their role as food providers." (TARA 2016)

Red painted African cattle with herders.

Internet photograph - public domain.

This

importance of cattle led to their portrayal in many cases as discrete

individuals instead of generic cattle. "Cattle

were perceived as having unique horns, especially among longhorn cattle which

occupied a large population. For instance, some cattle were given lyre-shaped

horns. Cattle were known to have a large financial, cultural, and environmental

impact on the people of the Ennedi highlands. They were also given distinct

coats to individualize these animals, and rock art at some sites including the

Chiguéou II site, includes cattle figures in extravagant geometric designs.

Cattle were found all among the highlands, while other animals, such as horses,

were not." (Stanley 2015)

Painted cow, Wadi el Firaq,

Internet photograph - public domain.

Therefore, African rock art portraying cattle must be viewed as a much

more complex phenomenon than just groceries or even wealth. They are viewed as

beautiful, objects of devotion and desire as well as a means of sustenance. "So there are many reasons why cattle

were, and still are, prized and cared for in many

African societies: beauty, hardiness, religio-spiritual use, social and

political value - and food." (TARA 2016)

In other

words, African cattle images can carry meanings and have implications pointing

to virtually all aspects of a culture and its value systems.

NOTE:

Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for

public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public

domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner

will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should

read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Heritage

Daily,

2020 Milk

Pioneers: East African Herders Consumed Milk 5,000 Years Ago,

https://www.heritagedaily.com/2020/04/milk-pioneers-east-african-herders-consumed-milk-5000-years-ago/127612

Noguera,

Alessandro Menardi

2016 The

Chiguéou II Rock Art Site Revisited (Ennedi, Chad), February 8, 2016,

https://independent.academia.edu/AlessandroMenardiNoguera

Stanley,

David

2015 Prehistoric

Rock Paintings at Manda Guéli Cave in the Ennedi Mountains - Northern Chad,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51016097

TARA

(Trust for African Rock Art),

2016 Cattle in

African Rock Art and Traditions, January 22, 2016,

https://africanrockart.org/news/cattle-in-african-rock-art/

Saturday, May 2, 2020

CONTEMPORARY ROCK ART - MANI STONES:

Mani stones, Diskit Monastery, India.

Photo www.amisingplanet.com.

Normally

we students of rock art think of our subject as a branch of art history -

something interesting that belongs to the past, but that is not always true.

There is a form of rock art that is not only contemporary, but people are still

earning a living by producing it - Buddhist Mani Stones. Most common in Tibet,

but also found in neighboring India, Nepal, and Bhutan, Mani stones are a

corporeal prayer, essentially a permanent supplication for blessing and enlightenment.

Mani stones, Kutsapternga, Nepal.

Photo www.amusingplanet.com.

"Mani

stones are stone plates, rocks and/or pebbles carved or inscribed with the six

syllabled mantra of Avalokiteshvara (Om mani padme hum, hence the name

"Mani stone"), as a form of prayer in Tibetan Buddhism. The term Mani

stone may also be used in a loose sense to refer to stones on which any mantra

or devotional designs (such as ashtamangala) are inscribed. Mani stones are

intentionally placed along the roadsides and rovers or placed together to form

mounds or cairns or sometimes long walls, as an offering to spirits of place or

genius loci. Creating and carving mani stones as a devotional or intentional

process is a traditional sadhana of piety to vidam. Many stones are a form of

devotional cintamani. The preferred technique is sunk relief, where an area

around each letter is carved out, leaving the letters at the original surface

level, now higher than the background. The stones are often painted in symbolic

colors for each syllable (om white, ma green, ni yellow, pad

light blue, me red, hum dark blue) which may be renewed when they

are lost by weathering." (Wikipedia 1)

The

most common inscription on Mani stones is the Buddhist mantra "Om Mani

Padme Hum."

"The

first word Aum/Om is a sacred syllable in various Indian religions. The word

means 'jewel' or 'bead', Padme is the 'lotus flower (the Buddhist sacred

flower), and Hum represents the spirit of enlightenment."

(Wikipedia 2)

"Carving

Mani stones is considered a form of meditation. Monks make them and so do local

villagers, and add them to mounds which grow bigger and bigger as time passes

by. The Jiana Mani Stone Mound in Xinzhai Village, of Yushu Tibetan Autonomous

Prefecture in China grew just like that." (Patowary

2015)

Yushu Jiana Mani stone mound,

Xinzhai Village, Yushu Tibetan

Autonomous Prefecture, China.

Photo tibetpedia.com.

"Yushu

Jiana Mani stone mound is the largest Mani stone mound in the world. It's said

that the local Tibetan Buddhist Master Jaina built a small Mani stone mound 300

years ago. Since then, people kept putting more Mani stones on the to pray and

collect merit. Now it has around 200 million stones, is 300 meters long, 3 meters

high, and 80 meters wide." (Tibetpedia 2017)

"Mani

stones can be seen in neighboring countries of Nepal and Bhutan as well, where

Buddhism is also widely practiced. Large examples of Mani stones resembling

tablets carved out of the sides of rock formations are in locations throughout

the Nepali areas of the Himalayas. Mani stones are also found around

monasteries in India, the true place of origin of the mantra where it was

orally transmitted through many generations. It is not known when the mantra came

into use, but the earliest recorded mentions of it occurred in the late 10th

and early 11th centuries in the Karandavyuha Sutra, which itself was compiled

at the end of the 4th century from an even earlier source." (Patowary

2015)

So,

not only are Mani stones a form of hard rock prayer, they are a demonstration

of devotion through sacrifice, either by putting in the work to create one, or

the money spent to purchase one, and a permanent offering for continued

blessing. A modern form of decorative rock art with a very serious meaning and

purpose, and supporting a class of contemporary professional rock art carvers.

NOTE:

Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for

public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public

domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner

will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should

read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Patowary,

Kaushik

2015 The

Sacred Mani Stones of Buddhists, amusingplanet.com

TibetPedia

2017 Mani

Stones, June 29, 2017, https://tibetpedia.com/lifestyle/mani-stones/

Wikipedia

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mani-stone

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Om_mani_padme_hum

Labels:

Buddhist,

India,

Mani stones,

Nepal,

petroglyphs,

rock art,

Tibet

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)