Sunday, October 20, 2019

SIGN AND GESTURE IN ROCK ART - PART 1: IMPLIED.

There are

many rock art enthusiasts who try to read written messages in the shapes and

relationships of the elements of a pictograph or petroglyph. I have generally

been a skeptic on this, I see no element of writing in North American rock art.

Australian Aboriginal rock art.

Internet, Public Domain.

Hawaiian rock art,

Photo. Paul and Joy Foster.

There is,

however, one facet of this question that I have to confess might in some few

cases have some validity. I am referring to portrayals of gestures that might have

meaning in a sign-based system of communication. Carol Patterson has done some

work with Australian Aboriginal and Hawaiian rock art where she found meanings

in arm and leg positions which strike me as plausible.

We are

accustomed to finding petroglyphs of Kachinas in the American southwest. Some

of them can be identified by their markings and shapes. Severin Fowles (2013)

points out that the identity of a kachina is also carried in his gestures and

motions. "The Kachina dance, to be

sure, involves masks and costumes that can be hung on walls and treated like

art in a conventional sense, just as the overall choreography can be diagrammed

and analyzed as a kind of finished product. It is quite clear, however, that

the fluid series of gestural movements are themselves the source of the dance's

potency. It is the dancer-in-motion - indeed, the community-in-motion that both

makes and is made by the 'art'." (Fowles 2013:71) Perhaps this gesture

and motion could also be portrayed by the position of parts of the image in a

panel of rock art.

"Each is distinguished not only

by the painting and decoration of his mask and body, but also by his songs, his

dance step, his call, and his bearing. One moves across the plaza with long

swaggering steps, another dances lightly from place to place, while a third

moves with stately dignity."

(Kennard 2002:4) In other words the identification of a Kachina would involve

recognition of motion (gesture) as well as visual appearance. "These differences in dance steps serve

to distinguish one Kachina from another; they become as essential

characteristics as the painting and decoration of a mask." (Kennard

2002:12)

The viewer,

recognizing the imagery of the mask and costume, associates the motions that go

along with it mentally. In the vernacular of modern art this would be called

"performance art", the image is only a remaining vestigial record of

the gestures/performance that were the point in the first place.

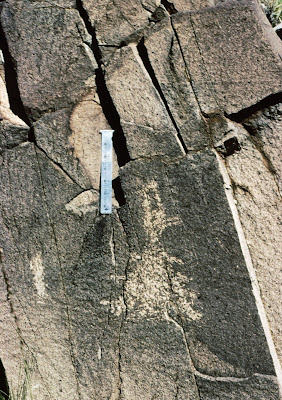

Shalako, stars, shield, and dragonfly,

Galisteo Dike, Comanche Gap,

New Mexico, Photo. Peter Faris.

Close-up of the Shalako,

Galisteo Dike, Comanche Gap,

New Mexico, Photo. Peter Faris.

On November

11, 2009, I posted a column in RockArtBlog titled Kachinas In Rock Art - The Shalako. In it I wrote the following about

these fascinating beings. "One very distinctive example

is the Shalako. Although they are not technically Kachinas, the Shalako dance in

pueblo ceremonials like the Kachinas. Resembling giant birds, the Zuni Shalakos

are up to ten feet tall. While dancing rhythmically, they clack their beaks.

They dance till near sunrise. The tall, conical and long-necked

form of the Shalako with their long beaks was probably derived from the

Sandhill crane."

Shalako, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Photo. Peter Faris, 1988.

Rock art depictions of the Shalako can

be dated back to the 14th century but its recent history is more

complex. In her book Kachinas in the Pueblo World, Polly Schaafsma described

the loss of much of the Kachina cult at Hopi. First through the efforts of the

Spanish after their conquest of the southwest to eradicate native religions and

supplant them with Christianity. This was conducted by the destruction of

religious items and shrines, even religious leaders on occasion. Among Pueblo

peoples this was manifested by burning Kachina masks, costumes and dolls, and

outlawing the dances and ceremonies. Then in the nineteenth century Hopi was

swept by smallpox epidemics which killed many of the elders who possessed the

ceremonial knowledge necessary for the rites.

This was apparently the case with

the Hopi Shalako. Its first recorded appearance at Hopi was in 1870 and its

second was in 1893. At the 1893 reappearance a Hopi informant stated that their

Shalako ceremony had not occurred for over 30 years. This Hopi Shalako was

based on the Zuni Sio Shalako, but the ceremony was Hopi based upon

reconstructions from memories. Schaafsma relates this story on pages 142 and

143 of her book Kachinas in the Pueblo World, University of New Mexico Press,

Albuquerque, 1994. She also related how the lost Hopi Shalako returned to Second

Mesa through the efforts of the great Hopi painter Fred Kobotie who painted a

reproduction based upon two tablitas he found in the basement of the New Mexico

Museum of fine arts, and recognized them as belonging to the Hopi Shalako based

on his memories of descriptions by his grandfather.

Zuni Shalako dance,

Internet, Public Domain.

Shalako mask pictograph, Zuni,

Village of the Great Kivas,

New Mexico. Photo. Teresa Weedin.

Shalako depictions are found in rock

art in the area of the Western Pueblos near both Hopi and Zuni, and are also

found in the Rio Grande area. The examples shown here are petroglyphs of

Shalakos from west of Albuquerque and from Galisteo dike east of the Rio Grande

and south of Santa Fe, and a beautifully painted contemporary pictograph of

Shalako from the panel of Kachina masks at the Village of the Great Kivas near

Zuni." (Faris

2009)

Zuni Shalako, early 1900s,

p.138,Classic Hopi and Zuni

Kachina Figures, photo Andrea Portago,

Mus. of NM Press, Santa Fe.

Sia Salako, Zuni Shalako, p.102,

Hopi Indian Kachina Dolls,

by Oscar T. Branson, 1992.

The Shalako

certainly have impressively distinctive shapes. "In the personization of these giants, the mask is fastened to a

stick, which is carried aloft by a man concealed by blankets which are extended

by hoops to form the body." (Fewkes 1985:66)

Seeing the

motions of this giant, birdlike being, with its head gracefully bobbing and

dipping high in the air, would be an unforgettable experience. And seeing the

image (the petroglyph or pictograph) of this being inevitably recalls the

accompanying sounds and motions. For me it always happened when my

grandchildren watched big bird on Sesame Street.

NOTE:

Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for

public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public

domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner

will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should

read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Faris, Peter

2009 Kachinas

In Rock Art - The Shalako,

November 11, 2009, https://rockartblog.blogspot.com

Fewkes, Jesse Walter

1985 Hopi Katcinas, Dover Publications, Inc.,

New York

Fowles,

Severin, and Jimmy Arterberry

2013 Gesture

and performance in Comanche Rock Art, pages 67-82, in World Art 2013, Routledge,

Taylor and Francis Group, UK.

Kennard, Edward A.,

2002 Hopi Kachinas, Kiva Publishing, Walnut,

CA.

Schaafsma, Polly

1994 Kachinas in the Pueblo World, University

of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque

Labels:

animation,

petroglyph,

pictograph,

rock art,

Severin Fowles,

shalako

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment