Saturday, May 28, 2016

SEEKING BEAR, A BOOK REVIEW:

Cover.

I want to introduce you to another wonderful book by Jim Keyser

and George Poetschat, Seeking Bear: The

Petroglyphs of Lucerne Valley, Wyoming, 236 pages. Published in 2015 by the

Oregon Archaeological Society Press, Portland, with well over 100 illustrations

and tables it is another in their series of in-depth studies of rock art of the

northern Great Plains and Basin. The Lucerne Valley, Wyoming, is an area in

southwest Wyoming that has not been studied extensively in the past, so this

volume greatly expands knowledge of rock art of that part of Wyoming and the

adjacent areas of Colorado and Utah.

Among these contributions to rock art knowledge are

documenting the presence of rock art styles in the Lucerne Valley which are

known from other areas, expanding the knowledge (at least my personal

knowledge) of them and enlarging the region that they are pertinent to. The first of these is the Classic Vernal

Style of Fremont rock art which is found so magnificently around Vernal, Utah, and

the Dinosaur National Monument. I had not known of any examples of that style

of petroglyph farther north than Brown's Park, Colorado (although it is close

enough to be expected). Also images in the Lucerne Valley were documented that

the authors attribute to the Uncompaghre Style of rock art, named for examples

around the Uncompaghre Plateau, south of Grand Junction, Colorado. Also the authors explain one image in terms of

the meaning of elements of the Dinwoody Style of petroglyph found in the Wind River

Valley farther north in Wyoming. These examples of relating images to styles

from other locations illustrates that the people of the Lucerne Valley were

tied in to the cultures of their larger world, whereas we have tended to

overlook that area as an isolated border region between other populations (once again affirming that it is dangerous to use our modern assumptions in evaluating past cultures).

In analyzing the images illustrated in the rock art panels,

Keyser once again illustrates his amazing ability to see fine detail and to

recognize elements overlooked by other people. This book provides many succinct

demonstrations of how much can be learned by really detailed examinations of

rock art. One example is a listing of six animals at one site and noting the

position of the tail of each animal. Elsewhere the shapes of antlers on cervids

are also compared.

One of the high points to me in reading this book is the

authors' ability to explain many of the concepts that we often feel strongly

about but have not reasoned through. On page 148, a discussion of rock art

symbols and their meanings provides a masterful summation of many of the

various popular and New Age explanations of rock art that frustrate so many

real students of the subject. Also, on page 186, their detailed presentation on

the perennial idea that rock art represents "hunting magic" could be

used in any college anthropology class on the subject.

All-in-all, Seeking Bear, is a highly detailed, relentlessly

educational presentation of the rock art from a little known area which ties it

inexorably into the larger whole world around it. My only (and I emphasize only)

criticism of this wonderful volume is its lack of an index. For someone like

me, who enjoys pursuing a train of thought, idea, or insight, through a volume

by referring to the index this was a frustrating absence. I actually had to

read it through from beginning to end, and perhaps this was their intention all

along. Watch out -you just might learn something. Once again, my gratitude to

Jim Keyser and George Poetschat for this contribution to rock art studies and

literature. Thank you.

Keyser, James D. and George Poetschat,

2015 Seeking Bear: The Petroglyphs of Lucerne

Valley, Wyoming, Oregon Archaeological Society Press, Portland.

www.oregonarchaeological.org.

Labels:

book review,

George Poetschat,

Jim Keyser,

Lucerne Valley,

petroglyph,

rock art,

Wyoming

Saturday, May 21, 2016

ROCK ART, AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLIGENCE:

Disclaimer: Except for the direct quotes following, the content of this posting is completely my speculation, and neither Dietrich Stout or Scientific American can be held responsible for any mistakes or errors.

We rock art enthusiasts have long believed that the beginnings of rock art indicated a certain level of intellectual development in our human ancestors. Now, a remarkable article in the April, 2016, Scientific American (Vol. 314, No. 4), by Dietrich Stout titled Cognitive Psychology/Tales of a Stone Age Neuroscientist, suggests that learning to make rock art may have been an important factor in that intellectual development.

We rock art enthusiasts have long believed that the beginnings of rock art indicated a certain level of intellectual development in our human ancestors. Now, a remarkable article in the April, 2016, Scientific American (Vol. 314, No. 4), by Dietrich Stout titled Cognitive Psychology/Tales of a Stone Age Neuroscientist, suggests that learning to make rock art may have been an important factor in that intellectual development.

Stout reported that he and his collaborators learned to knap

stone, to recreate Oldowan type stone tools (2.5 to 1.2 million years BP), and

Achulean type stone tools (1.6 million to 200,000 years BP). This process of

learning to knap stone, and then the production of the tools, proceeded with a

series of brain scans to attempt to identify any neural changes.

"We suspected that learning to

knap would also require some degree of neural rewiring. If so, we wanted to

know which circuits were affected. If our idea was correct we hoped to get a

glimpse of whether toolmaking can actually cause, on a small scale, the same

type of anatomical changes in an individual that occurred over the course of

human evolution.

The answer turned out to be a

resounding yes: practice in knapping enhanced white matter tracts connecting

the same frontal and parietal regions identified in our PET and MRI studies,

including the right inferior frontal gyrus of the prefrontal cortex, a region

critical for cognitive control. The extent of these changes could be predicted

from the actual number of hours each subject spent practicing - the more

someone practiced, the more their white matter changed." (Stout

2015:33-34)

Rhinos, Chauvet Cave.

Wikimedia. Public domain

Lion Man, Hohlenstein-Stadel.

Public domain.

But, what excited me more upon reading this is that the

creation of the two tool types left detectable differences in the brain

changes. This leads me to what I believe to the reasonable conclusion that the

creation of any two types of object would have different effects upon the

development of the brain of the creator. In other words, cave painting and

Paleolithic bone and ivory carving would have enhanced the development of the

brains of their creators, and thus I think I can safely assume that this would also

apply to the act of creating petroglyphs and pictographs. That the creation of this rock art not only signaled a

certain level of cognitive development, it actually contributed to that

development, and the different types of creations made different contributions to that

development.

"The results of

our own imaging studies on stone toolmaking led us recently to propose that

neural circuits, including the inferior frontal gyrus, underwent changes to

adapt to the demands of Paleolithic toolmaking and then were co-opted to

support primitive forms of communication using gestures and, perhaps,

vocalizations. This protolinguistic communication would then have been

subjected to selection, ultimately producing the specific adaptations that

support modern human language." (Stout 2016:35)

Westwater Creek, Bookcliffs,

Grand County, Utah.

Photograph: Peter Faris,

September, 1981.

Sproat Lake, Vancouver Island,

British Columbia, Canada.

Photograph: Peter Faris, 1995.

REFERENCE:

Stout, Dietrich

2016 Cognitive

Psychology: Tales of a Stone Age Neuroscientist, pages 28-35, Scientific

American, Volume 314, Number 4, April, 2016.

Wikipedia

Labels:

evolution,

language,

petroglyph,

pictograph,

rock art,

tool making

Saturday, May 14, 2016

PETROGLYPHS - DIRECT VS. INDIRECT PERCUSSION REVISITED:

Hammerstone below petroglyph

panel, Wild Horse Draw, Canyon

Pintado, CO. Photograph

Peter Faris.

On January 17, 2010, I posted a column on

http://rockartblog.blogspot.com, Petroglyphs - Direct Vs. Indirect

Percussion? In this I argued that most, if not all, petroglyphs had to be

created by direct percussion and gave the reasons for this belief. I was

recently informed by James D. Keyser of a paper that he and co-author Greer

Rabiega published in the Journal of

California and Great Basin Anthropology, 1999, Vol.21, No. 1, pages 124 -

136, entitled Petroglyph Manufacture by Indirect Percussion: The Potential

Occurrence of Tools and Debitage in Datable Context. Keyser's comments

concerning examples of indirect percussion are well reasoned and quite

convincing, and are based on experiments reproducing fine or narrow lines on

stone by striking a "chisel stone" with a hammer stone.

Rock art on boulder,

Airport Hill, St. George, UT.

Photograph Peter Faris, 2002.

In his e-mail to me Keyser stated :

"I just look for the evidence, and

where one finds very precise dints repeatedly aligned with one another to form

all or part of a design the chances are that that design (or the very precise

part of it) was produced by indirect percussion. Very finely made antlers (and

other extremities) on small images of deer in Valcamonica rock art are a good

example, but there are many others. Most often the examples of this sort of

work that I can think of off-hand are small parts of larger figures (but

the entire figure itself is still not very large—say a deer that can be covered

with a playing card)." (Keyser 2016)

"When a small part of a glyph

occurs routinely (like the aforementioned Valcamonica antlers) without even one

misplaced dint it begins to defy statistical probability that these were done

freehand—when such a simple solution (indirect pecking) was available and can

provide a guarantee that no dint will be miss-hit. If such finely produced

antlers were relatively rare—so that there were a few of many that had no

miss-hit dints, then one could argue that the very precise ones were simply

normal variation, but when one sees dozens of examples of such deer at site

after site—all of whom have antlers, legs, hooves, and open mouths—with nary a

miss-hit dint in the bunch—a student must begin to look for a way that this was

done that essentially “guarantees” accuracy EVERY TIME THE STONE IS STRUCK. Indirect percussion is

the only means by which this can be accomplished (with such a guarantee) that I

can come up with....I’d be glad to know." (Keyser 2016)

evidence of impact with the chisel

stone on its side. ( Keyser , James

D., and Greer Rabiega, 1999).

I am actually more convinced by what he did not find than by

what he did. Keyser reports large numbers of fine lines in petroglyphs with no

evidence of the mis-strikes that one would expect to find if only direct

percussion had been used to produce them. Now this is a telling argument and I

take it very seriously as I have to agree with Jim that the lack of missteps is

suggestive of an accuracy very difficult (I am sure he would say impossible) to

achieve with only direct percussion.

I do feel compelled to note, however, that this paper and communication are both about an experiment, and that he has not yet reported finding such chisel stones. Admittedly, there has probably been little awareness of their possibility so no one has looked for them. Also, Keyser also commented that as they are smaller and lighter than the hammer stones they may have regularly been carried away as useful tools, not dropped in the ground when the petroglyph is done as so many hammer stones were, " that’s the beauty of a chisel stone—you can carry two or three dozen of them with the same weight as a single good-sized hammer stone." (Keyser 2016)

I do feel compelled to note, however, that this paper and communication are both about an experiment, and that he has not yet reported finding such chisel stones. Admittedly, there has probably been little awareness of their possibility so no one has looked for them. Also, Keyser also commented that as they are smaller and lighter than the hammer stones they may have regularly been carried away as useful tools, not dropped in the ground when the petroglyph is done as so many hammer stones were, " that’s the beauty of a chisel stone—you can carry two or three dozen of them with the same weight as a single good-sized hammer stone." (Keyser 2016)

Bird Rattle carving petroglyph,1924,

Writing-on-Stone, Alberta, Canada.

Blackfoot.

I am enclosing this picture of Bird Rattle producing a petroglyph at Writing-on-Stone, Alberta, Canada, in 1924, as it is the only illustration I could find of petroglyph production in an authentic context. It really does not apply to the question here, however, as this petroglyph was produced by incising, not by pecking, so the techniques under discussion were not used by Bird Rattle.

Bird Rattle carving petroglyph,1924,

Writing-on-Stone, Alberta, Canada.

Blackfoot.

Note:

until such a chisel stone is reported in context at a petroglyph site this is

all conjecture based only upon logic and his reported experiments, but then my

original statement was also. Remember, the absence of proof is not proof of

absence. So, thank you to Jim Keyser for his information and help. I

appreciate that you took the time to help me clarify this question. Correction noted Jim, and thank you. I will temper my opinion accordingly.

And I also must confess that I have never examined the fine lines in a petroglyph for this phenomena, superimposition yes, mis-strikes no. So in the future I will have another line of evidence to look into.

Those who would like to dig a little deeper into this example are referred to the 1999 paper by Keyser and Rabiega, cited below.

And I also must confess that I have never examined the fine lines in a petroglyph for this phenomena, superimposition yes, mis-strikes no. So in the future I will have another line of evidence to look into.

Those who would like to dig a little deeper into this example are referred to the 1999 paper by Keyser and Rabiega, cited below.

REFERENCES:

Keyser, James D., personal communication, May 7, 2016.

Keyser , James D. and Greer Rabiega,

1999, Petroglyph

Manufacture by Indirect Percussion: The Potential Occurrence of Tools and

Debitage in Datable Context, Journal

of California and Great Basin Anthropology, Vol.21, No. 1, pages 124 - 136.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

GEOLOGY IN ROCK ART - A VOLCANIC ERUPTION AT PETROGLYPH POINT, MESA VERDE? - NOT BY A LONG SHOT:

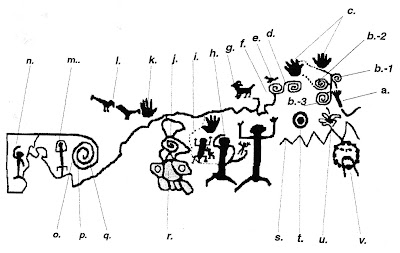

Petroglyph Point panel, Mesa

Verde, CO. Photograph Peter

Faris, 29 May 1988.

As a return visit to the subject of volcanoes in rock art, I

bring you another one of the fanciful creations by William Eaton (1999). This

is his interpretation of the petroglyph panel at Petroglyph Point in Mesa Verde

as a record of migration by early Puebloan peoples caused by a volcanic

eruption near Grants, New Mexico.

Close up of subject at Petroglyph

Point, Mesa Verde, CO. Photograph

Peter Faris, 29 May 1988.

Eaton's version of the

Petroglyph Point panel,

Fig. 12.5.1, p. 171.

" The subject petroglyph

included a subpanel of five volcanic cones with one in the process of

eruption." (Eaton 1999:170) This statement mystifies me as a simple

viewing of a photograph of the petroglyph panel shows a very different reality.

To begin with Eaton has just omitted many features of the actual panel. The

upper points of the zigzag line that Eaton identifies as five volcanic cones in

actuality show seven points. There are missing images from the left side, from

above the area recorded in his drawing, and almost the one fourth of the panel

on the right side is omitted. Additionally, in the area of the panel he has

illustrated there were many details omitted as well. For instance, there are

only three hand prints in Eaton's diagramming of the panel while I count six in

my photos of the real panel. Also, Eaton's drawing of the jet of molten

lava supposedly spraying out of this volcano has been somewhat altered from the

real petroglyph, and, indeed, the eruption he cited was not one of an explosive volcano

blasting upward. McCartys eruption consisted predominately of a flow of

pahoehoe lava from an 8 meter high cone. Pahoehoe lave is thin and flows

easily, often for long distances. It is not generally produced by an explosive

eruption, but by the liquid running out of a crack in the side of the

volcano.

Mesa Verde was occupied by Ancestral Pueblo peoples from ca.

AD 600 to 1300, approximately seven centuries. Eaton identifies the volcanic

feature that drove his imaginary migration to Mesa Verde as the McCarty's sheet

flow in the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic field. This lava flow occurred 2,500 - 3,900

years ago (1,900 - 500 BC) (geoinfo.nmt.edu). In other words, the lava flow

actually occurred between 3,100 to 4,500

years earlier than the period of full occupation of Mesa Verde.

Eaton's version of the

volcano, Fig. 12.5.1, p. 171.

"A petroglyph panel, some thirty feet in

length, is located in an isolated canyon two miles south of Spruce Tree House

in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. This panel, Figure 12.5.1, is unusual

because it offers possible documentary evidence in the form of metaphors of how

(and why) these early Pueblo Indians, migrated to Mesa Verde from their

previous homeland adjacent to the very active volcanic area of El Malpais

National Monument near Grants, New Mexico, circa A. D. 900." (Eaton

1999:179)

"Five volcanic cones in the Malpais area

near Grants, New Mexico, are shown in Figure 12.5.2. Item s represents Cerro

Negro (cone), Valley of the Volcanoes in El Malpais National Monument. The

second cone from the right - item u, McCartys Cone - which erupted circa A.D.

900. It produced lava flows 25 miles long." (Eaton 1999:173)

Lava Fissure in McCartys flow,

www.nmnaturalhistory.org

Early estimates of the age of the eruption of McCartys Cone

were based upon Native American tales and were wildly inaccurate. This appears

to be the date that Eaton has appropriated for his analysis. "Since then, accelerator mass

spectrometer radiocarbon dates of 2970±60 and 3010±70 years B.P. were obtained

on samples of burnt roots." (geoinfo.nmt.edu) These corrected dates for the lava flow were obtained

in 1994. These results show Eaton's

conclusions to be completely impossible. Note, the correct dating had been

published a number of years before Eaton wrote his fictional account, so

either the potential migrants were so scared by the eruption that they waited

paralyzed for 1,600 to 3,000 year before running away, or once again Eaton is

making up his own facts to support his bizarre theories. I am afraid I know

which one I believe.

REFERENCES:

Eaton, William M.

1999 Odyssey of the Pueblo Indians, Turner

Publishing Co., Paducah, KY.

https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/tour/federal/monuments/el_malpais/zuni-bandera/background.html

www.nmnaturalhistory.org

www.nmnaturalhistory.org

Labels:

mesa verde,

petroglyph,

rock art,

volcano Petroglyph Point

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)