A new theory has been put forward that inscriptions at Gobekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe and Sayburc in Turkey record a lunisolar calendrical system and also apparently also refer to the proposed comet impact that caused the Younger Dryas period. Well no, they don’t.

In 2024 Martin Sweatman of the Institute of Materials and Processes, at the University of Edinburgh School of Engineering wrote “Göbekli Tepe, an archaeological site in southern Turkey, features several temple-like enclosures adorned with many intricately carved symbols. It is located centrally among a group of Taş Tepeler pre-pottery Neolithic sites which include Karahan Tepe and Sayburç. Here, an earlier astronomical interpretation for Gobekli Tepe’s symbolism is supported and extended by showing how V-symbols on Pillar 43 in Enclosure D can be interpreted in terms of a lunisolar calendar system with 11 epagomenal days, which would make it the oldest known example of its type. Furthermore, it is shown how Göbekli Tepe’s 11-pillar enclosures and a megalithic 11-pillar pool structure at nearby Karahan Tepe can also be interpreted in terms of the same lunisolar calendar system. Other V-symbols at Göbekli Tepe are also interpreted in astronomical terms, and it is shown how the Urfa Man statue, a wall carving at Sayburç and a statue at Karahan Tepe that display V-symbol necklaces can be interpreted as time-controlling or creator deities. Symbolic links with later cultures from the Fertile Crescent are explored. Throughout, links are made with the Younger Dryas impact and Cauvin’s theory for the origin of the Neolithic revolution in the Fertile Crescent.” (Sweatman 2024:1) To me this is an example of how an academic can get into trouble when they stray too far out of their own particular field. Just as with Barry Fell’s nonsense, Sweatman’s theories are shaky at best, and **** at the very least. I have nothing against engineers, in fact I admire a good number of them and count them as friends, but, if I were to write a paper on some aspect of engineering I suspect that Sweatman would be among the first to criticize it. Martin, this is my field and I disagree with your conclusions.

And, you don’t have to take my word for it. Andre Costopoulos, Chair of the Arts and Anthropology Department of the University of Alberta (and someone with actual credentials in the field) wrote an excellent review of Sweatman’s paper in 2024 that analyzed and discussed its errors.

Sweatman claims that “earlier work provided an astronomical interpretation for some of Göbekli Tepe’s symbolism. Specifically, animal symbols on the broad sides of Göbekli Tepe’s pillars were interpreted as constellations similar to some of those from ancient Greece. In addition, Pillar 43 from Enclosure D was suggested to use precession of the equinoxes to display a date around 10,950 ± 250 BCE and interpreted as a memorial to the Younger Dryas impact event.” (Sweatman 2024:2) Now the earliest hard date at Gobekli Tepe is approx. 9530 ± 215 BCE which would mean, remarkably, that its carvings are a record of an event which supposedly happened 1,000 earlier.

He goes on to state that “pillars 2 and 38 at Göbekli Tepe were suggested to describe the path of the radiant of the Taurid meteor stream which is thought to have caused this impact event. Also, Pillar 18, one of the two central pillars from Enclosure D, was suggested to symbolize a comet related to the impact event. If this interpretation is correct, it has profound consequences. Partly, this is because it implies that astronomical knowledge was far in advance of what is generally assumed for this time.” (Sweatman 2024:3) I can give credit to proposals of long-term memories in cultures, and a certain amount of astronomical knowledge among ancient and pre-literate cultures. But I just cannot quite believe that these people understood that a fragment of a comet had collided with the earth one thousand years earlier (which theory, by the way, is contested).

And as far at the V-symbol’s significance, Sweatman states that “Pillar 43 is split into two sections by rows of V-symbols and small box-symbols. The lower, main portion has a circular disc symbol supported above the wing of a bird of prey. Below this bird symbol is a scorpion symbol. If the circular disc represents the sun, as expected, then the animal symbols probably represent constellations. In particular, the scorpion reminds us of the Greek Scorpius constellation. Its position relative to a circular disc clearly points to an astronomical interpretation.” (Sweatman 2024:9) I find a problem in identifying the various V-symbols as astronomically important, no where I can see in his paper does Sweatman state what the V-symbol actually represents. It seems he is basing his conclusions on an unidentified fact.

And herein

lies another problem, a trap fallen into quite frequently by writers on things

archeoastronomical. They assume that the names and identities of the

constellations we see in the night sky have always been the same. The sad fact

is we have no idea what, if any, constellations the inhabitants back then

imagined in the night sky, and yet Sweatman bases his conclusions on

identifying the constellations that are supposedly portrayed in carved stone.

“Let us now return to Pillar 33 from Enclosure D. This is the only other pillar at Göbekli Tepe known to exhibit V-symbols. Earlier, it was explained how Pillar 33 can be viewed as a picture of the Taurid meteor stream if the animal symbols on its broad faces correspond to the constellations Pisces (tall birds) and Aquarius (fox), with the snakes representing meteors. Indeed, it was suggested that it shows how the Taurid meteor stream radiant moves from Aquarius to Pisces over the course of a few weeks. However, Pillar 33 also has V-symbols on its inner, narrow face. On the right, 13 V-symbols ascend vertically, while on the left there are 14. As for Pillar 43, these are expected to represent the counting of days. In this case, these symbols might count the duration of the meteor shower from the direction of each constellation as the radiant point moves over the course of nearly one lunar month; 13 days from the direction of Aquarius (the fox) and 14 days from the direction of Pisces (the tall bird). Thus, interpretation of the V-symbols as representing individual days is consistent across Göbekli Tepe and supports the earlier interpretation of Pillar 33.” (Sweatman 2024:37-8) Some carved animals and V-symbols represent a meteor stream, based on what? Give me a break.

And now to Costopoulos’ review of Sweatman’s article. Andre Costopoulos, Chair of the Arts and Anthropology Department of the University of Alberta (and someone with actual credentials in the field) wrote an excellent review of Sweatman’s paper in 2024 that analyzed and discussed its errors.

We

first need to establish the credentials of the source. “Despite being published in a peer reviewed journal, the study is what

I would call scaffolded speculation. It consists of a collection of completely

untestable and largely unrelated hypotheses, piled on top of one another, to

reach an exceedingly unlikely conclusion.” (Costopoulos 2024:1) It makes

one wonder exactly whose peers reviewed Sweatman’s paper? I doubt that they

were archaeologists or art historians.

The whole Sweatman premise is basically a house of cards. “This is apparent in the structure of the

article itself, in which the phrase “If this interpretation is correct”, or a

close variation of it, occurs no fewer than five times at critical points in

the argumentation, with no attempt at finding out whether those proposed

interpretations are actually correct. And this ignores all the previous

speculations published by the author, and which are also called on for key

support of the argument.” (Costopoulos

2024:1) Too often we see this in articles supposing to explain meaning in rock

art. On one page a “this may mean” becomes assumed as a proven fact on

subsequent pages, Costopoulos’ “scaffolded speculation.”

And Costopolis gets to the crux of his argument. “Their entire interpretation rests on the associations they propose between the constellations and the animal carvings. In order to accept every other argument that follows, including this recent 2024 paper, one has to accept those identifications. As far as I can tell, Sweatman and Tsikritsis make no attempt to actually test the validity of their associations. They just visually match constellation stick figures with stone carvings on the pillar. Frankly, I think I could do just as well finding matches for the constellations on a page of a Beatrix Potter book.” (Costopoulos 2024:3) This goes back to my point about the supposed identification of stellar constellations in the night sky all those millennia ago. We just cannot know this.

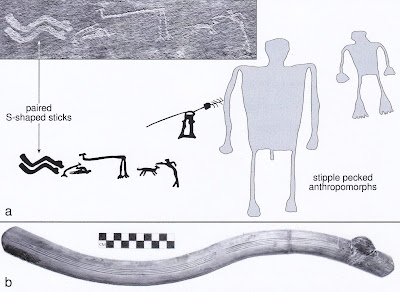

The main premise of Sweatmans’ paper is somewhat confusing. Half of it discussed the supposed Gobekli Tepe calendrical system based on identifying animals as constellations, and the other half tries to present it as proof of the supposed Younger Dryas comet impact, which is not universally accepted as scientific fact. “The other “established fact” in this system of hypotheses is that there was a Younger Dryas comet impact at all. This is far from certain, and given the current state of scholarship on the question, while it is not completely out of the question, I would say it is exceedingly unlikely. In other words, the scaffolded speculations about the Göbekli Tepe animal carvings are used to support the scaffolded speculations about the YDI. And all of it rests on claimed associations between stick figures and some really stunning and rich animal carvings at an archaeological site in Turkey.” (Costopoulos 2024:4) The stick figures referenced here are drawings of portions of stellar constellations and asterisms that Sweatman identified with the carved animals.

Enough beating on poor Martin Sweatman. I believe he is totally convinced of the truth of his speculations and excited about the new contributions he is making to our knowledge, but it is just this excitement that can lead us astray. We forget to apply critical analysis to our own suppositions. Gobekli Tepe is certainly a fascinating subject, we just need to be careful and self-analytical when we try to understand it.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

PRIMARY REFERENCES:

Costopoulos, Andre, 2024, The Gobekli Tepe calendar and the Younger Dryas Impact: another major media fail, 16 August 2024, ArcheoThoughts blog, https://archeothoughts.wordpress.com. Accessed online 17 October 2024.

Sweatman, Martin B., 2024, Representations of calendars and time at Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe support an astronomical interpretation of their symbolism, Time and Mind, 24 July 2024, DOI:10.1080/1751696X.2024.2373876. Accessed online 6 August 2024.

SECONDARY REFERENCE:

Sweatman,

M. B., and D. Tsikritsis,

2017, “Decoding

Göbekli Tepe with Archaeoastronomy: What Does the Fox Say?” Mediterranean

Archaeometry and Archaeology 17 (1): 233–250.