On 10 March 2018, I published a column in RockArtBlog titled “Ancient Saudi Guest Artists-In-Residence” about life sized carvings of camels found in northern Arabia. At the time I explained my reference to guest artists-in-residence as follows: “In university art departments there is a common practice known as the artist-in-residence. This is usually a working artist brought in from outside the university for a term to provide the students a good example of a working artist as well as broaden their range of experience. At first glance, these relief carvings, apparently done by someone who came from somewhere else, reminded me of artists-in-residence.” (Faris 2018) I likened this to the carvings which were assumed to have been done by members of a camel caravan en-route to somewhere which had stopped to rest or conduct business, someone from elsewhere who appeared, stayed for a period of time while he carved the camel images, and then passed on to somewhere else.

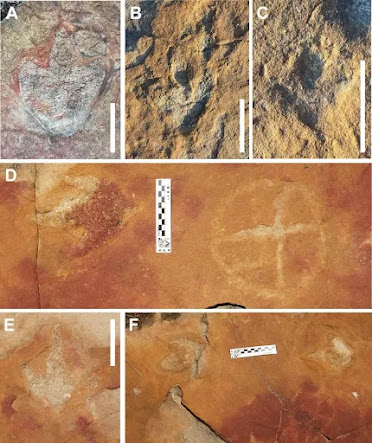

"Camel carvings have also been found at other sites in Saudi Arabia; one discovered five years ago in Al-Jalouf province has been described as a 'parade of live-sized camels.' In this new effort, the team was studying a rocky outcrop near the southern edge of the Nefud desert. The outcrop was known to researchers, but it took a closer look to discover artwork etched onto its surface by people living in the area thousands of years ago. The new team found several dozen images of a species of camel that has been extinct for thousands of years. Prior research has suggested that such camels once lived all across the Arabian Peninsula. The outcropping has been named Sahout - images were found on three of its formations." (Yirka 2023) All of the panels appear to demonstrate considerable wind erosion from blowing sand. They must have been quite difficult to record.

“The life-sized, naturalistic reliefs at the Camel Site in northern Arabia have been severely damaged by erosion. This, coupled with substantial destruction of the surrounding archaeological landscape, has made a chronological assessment of the site difficult. To overcome these problems, we combined results from a wide range of methods, including analysis of surviving tool marks, assessment of weathering and erosion patterns, portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, and luminescence dating of fallen fragments. In addition, test excavations identified a homogenous lithic assemblage and faunal remains that were sampled for radiocarbon dating. Our results show that the reliefs were carved with stone tools and that the creation of the reliefs, as well as the main period of activity at the site, date to the Neolithic. Neolithic arrowheads and radiocarbon dates attest occupation between 5200 and 5600 BCE. This is consistent with measurements of the areal density of manganese and iron in the rock varnish. The site was likely in use over a longer period and reliefs were re-worked when erosion began to obscure detailed features. By 1000 BCE, erosion was advanced enough to cause first panels to fall, in a process that continues until today. The Camel Site is likely home to the oldest surviving large-scale (naturalistic) animal reliefs in the world.” (Gaugnin 2021) The re-working of the camels is interesting, somewhat like aboriginal Australian traditional owners of rock art sites re-painting or re-carving them to preserve them.

“The data indicates that the sculptures were made with stone tools during the 6th millennium BCE. At this time, the regional landscape was a savanna-like grassland scattered with lakes and trees where pastoralist groups herded cattle, sheep and goats. Wild camels and equids also roamed the area and were hunted for millennia.” (Max Planck 2021)

Taken altogether these camels tell us a lot about the climate at the time they were created. Also, the fact that they were done in life-size, as well as the fact that the panels were anciently re-worked suggests the high esteem that this culture held the camels in, and the importance of their images to that culture. And the re-working also tells us that esteem lasted for a long enough period that the erosion of the panels was seen as a problem.

NOTE: Some images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Faris, Peter, 2018, Ancient Saudi Guest Artists-in-Residence, 20 March 2018, RockArtBlog, https://www.blogger.com.

Gaugnin, Maria et al., 2021, Life-sized Neolithic camel sculptures in Arabia: A scientific assessment of the craftsmanship and age of the Camel Site reliefs, Sciencedirect.com, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103165. Accessed online 17 October 2023.

Max Planck Society, 2021, Life-sized camel carvings in Northern Arabia date to the Neolithic period, 15 September 2021, https://phys.org/news/2021-09-life-sized-camel-northern-arbia-date.html. Accessed online 17 October 2023.

Yirka, Bob, 2023, Life-size images of extinct camel species found carved into stones in

Saudi Arabia, 4 October 2023, https://phys.org/news.

Accessed online 4 October 2023.

.png)

.png)