On 2 January 2021, I reported on the reporting of extensive pictograph panels at a site in Colombia known as La Lindosa (Morcote-Ríos et al. 2020). These early reports claimed that many of the pictographs at this site were of Pleistocene megafauna and I expressed skepticism about a large percentage of these. However, it is a magnificent site, perhaps one of the most extensive rock art sites known, and certainly worth study and reporting. Now, a new report has addressed the dating of La Lindosa’s occupation.

“The eight-mile Cerro Azul rock art mural at Serrania de la Lindosa in Colombia’s Guaviare region, on the banks of the Guayabero River, has been the subject of recent expeditions led by Jose Iriarte, and archaeologist at the University of Exeter. Now the ocher paintings have become the subject of debate, as experts attempt to definitively date them and identify the animals.” (Contributor 2022)

Radiocarbon

dating was performed on charcoal and charred seeds excavated from the rock

shelters at the site, and provided a range of occupation dates. It was then

assumed that the painting was conducted at the same time that the rock shelters

were occupied, and by the same people who did the painting.

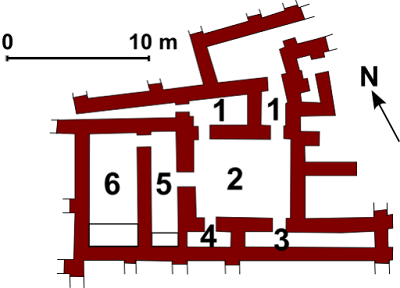

“During three archaeological field seasons (2015, 2017 and 2018), we carried out excavations in three rock shelters (Cerro Azul, Cerro Montoya and Limoncillos), where lithic artifacts, charred seeds, animal remains, ochre fragments and charcoal were recovered in the stratigraphic deposits of these sites. These three rock shelters exhibit large concentrations of rock art paintings, though at varying degrees of preservation. The dating of these sites allowed us to establish the chronological framework for the rock art of La Lindosa, with dates ranging from the late Pleistocene approximately 12.6 ka to the European arrival approximately 1478-1642 AD.” (Iriatre et al. 2022) This gives a very broad range for the production of imagery at this location, essentially from the Holocene to Historic periods. Dating of the rock art has so far been indirect, based on dates from carbon recovered from the same strata as fragments of ochre found in excavations in rock shelters below the paintings with researchers assuming that this represents the same ochre that was used to do the paintings.

“At Cerro Azul, two charcoal samples yielded LGM dates ~20,500 – 19,200 BP. Both dates were obtained from charcoal recovered in Stratus II, which is composed of natural sediments mixed with some chert flakes, charred seeds and charcoal. Until future excavations can provide a more securely defined context for the looser strata of the site, clearly identifying the cultural origins of the LGM dated charcoal, rather than charcoal fragments produced by natural fires, we presently only accept the Terminal Pleistocene dates of the site as firm evidence of human activity. Two radiocarbon assays made on charred palm seeds from secure cultural contexts provide Terminal Pleistocene dates between ~12,100 and ~11,800 BP. These dates mark the start of stable, repeated human activity in the region. Three dates from charred palm seeds through the Early to Middle Holocene (~9,090 - ~7,004 cal. BP) demonstrate continued activity in the region. A late Holocene date of ~3,002 – 2,849 cal BP marks the last preceramic strata. Ceramics are present by 2,929 – 2,779 cal BP, 15-20 cm b.s.”(Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar, et al. 2020:6) So, the two oldest dates (~20,500 – 19,200 BP) are not used because it is not considered probable that this charcoal is the result of human activity without more evidence. At this time those dates are being classified as possibly the result of natural forest fires adjacent to La Lindosa.

“At Cerro Azul fragments of ochre were recovered from the lower levels, suggesting that paintings were produced from the oldest occupations as an early strategy of creating and defining the cultural landscape.” (Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar, et al. 2020:13) These lowest levels of the excavation were directly dated by radiocarbon dating. So the oldest dates prove that people were there by 20,500 to 19,200 BP, but not conclusively that they actually did the paintings. The researchers had to assume that the traces of ochre that they found in the same strata as the dated carbon had fallen or spilled during the act of creating the rock art - a reasonable assumption.

In my previous column

on the rock art at Serrania de la Lindosa I wrote “It is always exciting to find a record that illustrates extinct

animals, and this discovery, because of its large scale, provides a wealth of

new possibilities for research. While some of the illustrations of extinct

creatures are easy to identify, others take a little more imagination. All in

all though, this is a world class, major discovery.” (Faris 2021) With the

addition of dates, even if they are not yet 100% certain, I find the

rock art at Serrania de la Lindosa even more potentially valuable and exciting.

NOTE: Images in this posting were retrieved from the internet with a search for public domain photographs. If any of these images are not intended to be public domain, I apologize, and will happily provide the picture credits if the owner will contact me with them. For further information on these reports you should read the original reports at the sites listed below.

REFERENCES:

Contributor, 2022, Giant Sloths, Ancient Elephants, and Ungulates: Prehistoric Rock Art in the Amazon May Depict Extinct Ice Age Animals, a New Study Says, 9 March 2022, https://massive.news/2022/03/09/

Faris, Peter, 2021, Colombian Rock Art Claimed to Depict Extinct Megafauna, 2 January 2021, https://rockartblog.blogspot.com/search/label/Colombia.

Iriarte, Jose et al., 2022, Ice Age megafauna rock art in the Colombian Amazon?, 7 March 2022, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol. 377, issue,1849, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0496, accessed 12 March 2022.

Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar, et al., 2020, Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late

Pleistocene and the Early Holocene - New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa,

Quaternary International, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.026