Saturday, October 31, 2015

A COSMIC HOAX:

Station #16, Nine-Mile Canyon, UT.

Photograph Peter Faris, 1993.

Close-up of panel at Station

#16, Nine-Mile Canyon, UT.

Photograph Peter Faris, 1993.

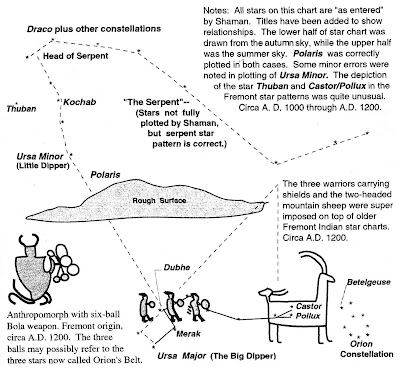

In this column I am presenting another egregious mistake

from the book Odyssey of the Pueblo

Indians by William Eaton. On page 145 he presents a petroglyph panel that

he calls a "Pueblo (Fremont) Star Chart". That is his identification

of the well-known petroglyph panel from Station 16, in Nine-Mile Canyon, Utah.

One identification that I take exception to is what he calls

the two-headed mountain sheep. Upon careful examination of the petroglyph

Eaton's second head at the back of the animal is actually a conglomeration

composed of its tail and a couple of curved lines descending from an unknown

mark that has been destroyed by the impact of a large caliber bullet. The

remains of this mark can be seen circling around to the upper right of the bullet

crater.

On the left of this panel is a figure that Eaton calls an

"anthropomorph with a six-ball bola weapon." Now this is a very

interesting figure and does, in fact, remind one of a figure holding a bola. This

figure along with numbers of carefully rounded stone balls found at Fremont

sites have prompted this same identification by many other rock art

researchers. It is an interesting speculation, but one that has not been

proven. For some reason, and absolutely without any evidence at all Eaton has

claimed that "the three balls may possibly refer to the three stars now

called Orion's Belt." Which three balls Mr. Eaton? As you pointed out

there are six.

Then Eaton went on to identify the constellations Ursa

Major, Ursa Minor, and Serpens, as well as a few other stars including Polaris

in additional marks on the cliff face. Unfortunately, the majority of the stars

that Eaton identifies in this panel are, in reality, bullet holes put there by

Anglos much later than the petroglyphs. In many places, we find that

petroglyphs and pictographs provided seemingly irresistible targets to

gun-toting vandals. These unfortunate marks have never had anything to do with

Fremont or Pueblo Native American groups. Additionally, to make the constellation Serpens out of those bullet holes Eaton had to flip the constellation entirely as can be seen in the star chart below.

Star chart of the summer sky showing

Serpens to the left of center. From

Howard, The Telescope Handbook

and Star Atlas, 1967, p. 39.

This so-called "Pueblo (Fremont) Star Chart" is

just another mistaken example of someone who feels compelled to try to force

the facts to fit a theory that they bear no relation to in the real world.

While I applaud Mr. Eaton's enthusiasm, I do have to deplore his methods and

results.

REFERENCES:

Eaton, William M.

1999 Odyssey of the Pueblo Indians, Turner

Publishing Co., Paducah, KY.

Howard, Neale E.

1967 The Telescope Handbook and Star Atlas,

Thomas Y. Crowell Co., New York.

Labels:

9-Mile canyon,

constellation,

petroglyph,

rock art,

stars,

Utah

Monday, October 19, 2015

GLOBAL ROCK ART DATA BASE:

Global Rock Art Data Base home page.

An interesting

new development in rock art recording has come out of Australia with Robert Haubt's

Global Rock Art Database (GRADB). Unlike most rock art Internet sites which

focus on "see my pretty pictures," or using rock art to prove

Creationism, or any of the other many personal goals of the creators of the

websites, Haubt has built a framework for projects and data from all over the

world. I believe his aim is to, in effect, build the central library for

everyone's rock art studies. Even at its early stages the GRADB provides a

wealth of interesting information and provides links to many projects and

destinations. This project forms part of his "PhD thesis which is looking at digital

data management in rock-art heritage." (Haubt 2015)

The Rock Art

Data base currently has "over 200

sites, projects, and other resources currently listed on a world map. The Rock

Art Database brings together hundreds of rock-art projects from around the

world in one centralized hub. Find some of the most amazing rock-art places

from around the world through our interactive map and explore stunning media

galleries showcasing photographs, videos, 3D models and virtual tours."

(Haubt 2015)

"Mission:

The Rock Art Database is a non-for

profit online project at PERAHU, Griffith University in Australia. It seeks to

improve theory and practice in the digital curation of rock art data through

building a centralized global heritage community network. Through the use of

new technologies the database offers new ways to look at heritage data and

explores the potential in digital curation." (Haubt 2015)

This is a very

ambitious project which I believe will prove to be of great value. It will

eventually include "Interactive

Media Presentations: hundreds of photographs, maps, 3D models, Virtual

Tours." (Haubt 2015)

His stated goal

is to provide a resource will contribute to developing a rock art community

where people can "upload, manage,

share, and discuss, to assist conservation, preservation and

education in theory and practice by making rock-art related issues more

accessible and more visible. " (Haubt 2015)

Check this out

for yourself. Go to http://www.rockartdatabase.com/v2/, see the exciting

possibilities, and get on board with Robert Haubt and the Global Rock Art Data

Base.

REFERENCES:

Robert Haubt

(personal communication).

Saturday, October 17, 2015

PALEOLITHIC HORSE DOMESTICATION?

Paleolithic Horse paintings from Chauvet cave.

Photo from www.bradshawfoundation.com.

There is an interesting school of thought today that

maintains that cave paintings of horses, as well as horse effigies carved in

bone or antler, contain clues that point to domestication of the horse by Magdalenian people. One of the major proponents of this interpretation is Paul Bahn. I have elsewhere expressed my great admiration for Paul Bahn for his imaginative approach to interpreting cave art, and his willingness to confront and argue against dogma. I am afraid, however, that in this instance I find myself in the position of arguing against Bahn.

"15. Carving of a horse head from Saint-Michel d'Arudy, France, showing facial lines that indicate the line demarcating the mealy muzzle and the natural contours of the face. These lines have been interpreted by Bahn to represent a bridle. (Drawing courtesy of Randall White)" (Olsen 2003:5)

"The strongest evidence

presented for the control of horses at this early date consists of depictions

of what Bahn (Paul) interprets as bridles on the heads of horses in wall

engravings and effigies carved in stone or antler. These artistic renderings

display lines encircling the nose and running from the nose back toward the ear

(figure 15). At first glance these lines could be interpreted as part of a

bridle, including the nose band, chin strap, and cheekpieces. On closer

inspection, however, it is clear that these lines represent natural features on

the heads of the Pleistocene horses. The wild Asiatic (Przewalski) horse, which

is colored like many of the prehistoric depictions of the European Ice Age

horses, has what is known as a mealy muzzle, or pale cream-colored ring around

the end of the snout (figure 16). This is one of the characteristics of what is

today called a Pangare' coat pattern on horses. Although there are no clear

examples of a mealy muzzle in cave paintings, it is possible that some of the

engravings with lines around the nose are meant to portray this change in

coloration around the tip of the muzzle. The horizontal lines running from the

nose back toward the neck probably represent natural contours or the horse's

head. Curved lines are often incised to represent the contours of the large

masseter muscle at the back of the lower jaw, and some lines indicate changes

in fur patterns. Similar lines are seen on engravings of bison and other

animals, although their positions are slightly different, but no one has

suggested that bison were domesticated. (Olsen 2003:54)

Paleolithic baton de commandment. Public

domain photograph from the internet.

"Bahn also believed that the

Paleolithic batons de commandment were cheekpieces for a bridle. Although they

bear a vague similarity to much-later Bronze Age antler cheekpieces, the batons

are generally larger and heavier with only one very large perforation near one

end. Bronze Age cheekpieces typically have two or three holes for the leather

straps." (Olsen 2003:55)

"Further, Bahn presented

examples of damage on incisors (the anterior teeth) of Paleolithic horses that

he hypothesized was caused by the nervous habit of crib-biting. This practice

has been observed in horses that get bored with being penned and begin to chew

on their stalls. If this behavior occurs only in situations where the animal is

enclosed by a human-made structure, then surely horses were being controlled in

the Paleolithic. R. A. Rogers and L. A. Rogers have shown, however, that

similar damage appears on horse incisors dating to the early and middle

Pleistocene of North America, long before the arrival of humans, Littauer

pointed out that such wear could have just as easily been formed when the

animals browse on the bark of trees." (Olsen 2003:55)

"Some scholars, notably Paul

Bahn, have suggested that horses were at least managed an perhaps domesticated

20,000 years ago by Ice Age hunter-gatherers who created the cave paintings,

ornaments, and mobile art of the Upper Paleolithic (see chapter 3). This idea

has been widely popularized by Jean Auel in her best-selling fiction books

beginning with Clan of the Cave Bear.

Stocky, thick-legged, large-headed

horses living throughout Europe during the Pleistocene Ice Ages were depicted

magnificently in cave paintings and sculpted bone objects by Upper Palaeolithic

artists, particularly in southwest France and northern Spain. Some of these

depictions seem to show rope halters around horse heads (see chapter 3, figure

1). This interpretation is convincing at first. However, the shaggy winter coat

of the modern Przewalski horse often sports a line of tufted hair running down

the cheek and around the nose in exactly the positions marked by the

"halter" lines in Paleolithic art. The "winter coat"

interpretation of these lines is simpler and more likely than an interpretation

based on bridling.

Some Upper Paleolithic horse teeth

exhibit odd wear that Bahn has suggested resembles the wear caused by

crib-biting, a vice associated with stalled or penned horses. However, similar

wear has been found on the teeth of Early Pleistocene equid fossils from

America, animals that could not possibly have been domesticated because they

predate the evolution of both modern humans and horses (see chapter 3). There

has never been a controlled study that reliably identifies the diagnostic

traits of cribbing wear on equid teeth so that it can be positively

distinguished from natural wear or incidental damage to the incisors. The

crib-biting suggestion remains untested and inherently unlikely. It would

require not only domestication but long-term stalling of horses by Paleolithic

hunters.

On the whole there is little

archaeological evidence even for herd management and no convincing support for

domestication associated with the Ice Age horses of the European Upper

Paleolithic." (Anthony 2003:69)

Wood chewing, or

crib-biting, is behavior in which the horse gnaws on wood rails or boards as if

they were food. This behavior eventually gives a distinctive wear pattern on

the horse's teeth that a good veterinarian can identify in making his

diagnosis. Wear patterns resembling this have been found on some teeth on

Paleolithic (Ice Age) horse skeletons which has led some investigators to rash

statements that this is proof of horse domestication that early. In other words,

Cro-Magnon supposedly had built corrals and confined their domesticated horses

there, where they performed crib biting. I think that nothing could be further

from the truth.

Horses, both wild and domesticated, will chew wood on occasions. Where I

live in the American West, if a horse corral contains a cottonwood tree it is

almost invariable dead, the horses having girdled it by chewing the bark off.

Inner bark is a nutritious food that they purposely seek out, especially

when grazing conditions are poor. If drought has prevented normal grass growth

for grazing, or if deep snow has covered the grass, horses will naturally turn

to chewing the bark on trees. Indeed, ethnographic reports of Plains Indian tribes

tell us that they sometimes kept their favorite horse tethered by their tipi in

winter encampments which were usually in a heavily wooded area to provide some

protection from cold winds. The owners of these horsed would gather branches of

surrounding cottonwood trees to feed these horses which readily chewed off the

bark and ate small twigs and branches. This bark was supposedly nutritious enough that the horses reportedly could put on

weight on such a diet, even during harsh winter conditions. With reasonable explanations for the marks on the carvings and paintings that might resemble harnessing, and with a reasonable explanation for wood chewing by horses, I believe that the preponderance of evidence is against the proposed domestication of horses in the paleolithic period. Additionally, I can think of no way that evidence of crib-biting could be deduced from the paintings or carvings of the Paleolithic period. Therefore, with this analysis, I think that we can make an informed judgement on the question of domestication and, to me, all the evidence argues against it.

REFERENCES:

Anthony, David W.,

2003 Bridling Horse

Power, chapter 4, p. 58-82, in Horses

Through Time, edited by Sandra L. Olsen, Roberts Rinehart Publishers,

Boulder, for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Olsen, Sandra L.,

2003 Horse Hunters

of the Ice Age, chapter 3, p. 35-56, in Horses

Through Time, edited by Sandra L. Olsen, Roberts Rinehart Publishers,

Boulder, for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Labels:

cave painting,

Chauvet,

domestication,

Horse,

paleolithic art,

Paul Bahn,

rock art

Saturday, October 10, 2015

POSSIBLE OLDEST PETROGLYPH IN SOUTH AMERICA DISCOVERED:

An online article by Charles Q. Choi, a contributor to

LiveScience, explains the discovery of what might be the oldest petroglyph in

South America, in a cave named Lapa do Santo in central-eastern Brazil.

The region is home to Luzia, the oldest human skeleton found

to date in South America. Discovered at Lapa Vermelha, Brazil, in 1975, by

archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire, the skeleton has been dated to ca.

11,500 BP. Luzia's remains were not articulated.

Her skull was separate from the rest of the skeleton and was buried under forty

feet of mineral deposits and debris, but was in surprisingly good condition.

Although flint tools were found nearby, hers were the only human remains found.

In 2013 new dating of the bones provided an age of 10,300 ± BP (11,243 - 11,070

BP). (Wikipedia)

Human remains of that age in the same region presents the

possibility that the petroglyph could conceivably also be that old.

"Lapa do

Santo is one of the largest rock shelters excavated yet in the region, a

limestone cave covering an area of about 14,000 square feet (1,300 square

meters). Here, researchers have found buried human remains, tools made of stone

and bone, ash from hearths, and leftovers from meals of fruit and small game.

In 2009, a team headed by Walter Alves Neves digging about 13 feet (4 meters) below the surface,

the scientists found a rock carving or petroglyph of a man packed into the side

of the cave. 'The figure, which appears to be squatting with his arms

outstretched, is about 12 inches (30 centimeters) tall from head to feet and

about 8 inches (20 centimeters) wide'. The engraving is also

depicted with a relatively large oversized phallus about 2 inches (5 cm) long,

or about as long as the man's left arm. 'We named the figure 'the little horny

man,' Neves said." (Choi

2015)

" 'The figure is probably linked to some kind of fertility ritual,' Neves told LiveScience. 'There is another site in the same region where you find paintings with men with oversized phalluses and also pregnant women, and even a parturition (childbirth) scene.' Carbon dating and other tests of the sediment covering the petroglyph suggest the engraving dates between 9,000 and 12,000 years old. This makes it the oldest reliably dated instance of such rock art found yet in the Americas." (Choi 2015)

"When this carving is compared with other examples of early rock art found in South America, it would seem that abstract forms of thinking may have been very diverse back then, which suggests that humans settled the New World relatively early, giving their art time to diversify. For instance, at one site in Argentina named Coeval de lass Manos, paintings of hands predominate, while at another site there, Cueva Epullan Grande, engravings have geometric motifs. ' It shows that about 11,000 years ago, there was already a very diverse manifestation of rock art in South America, so probably man arrived in the Americas much earlier than normally is accepted,' Neves said." (Choi 2015)

And the old "Clovis first" dictum continues to

crumble.

NOTE: The scientists detailed their findings February 22,

2015, in the online journal PloSONE.

REFERENCES:

Choi, Charles Q.,

2015 Little Horny

Man: Rock Carving of Giant Phallus Discovered, http://www.livescience.com/, February 22, 2015.

Wikipedia.

Labels:

Lapa do Santo,

petroglyph,

rock art. Brazil,

South America

Saturday, October 3, 2015

A PALEOLITHIC PALIMPSEST:

Gonnersdorf, Germany. From

Bahn and Vertut, 1997.

"A palimpsest is a manuscript page from a scroll or book that has been scraped off and used again. The word "palimpsest" comes through Latin from Greek παλιν + ψαω = (palin "again" + psao "I scrape"), and meant "scraped (clean and used) again." Romans wrote on wax-coated tablets that could be smoothed and reused, and a passing use of the term "palimpsest" by Cicero seems to refer to this practice. - - The term has come to be used in similar context in a variety of disciplines, notably architectural archaeology." (Wikipedia)

In art cases the term palimpsest is usually used to describe a composition with traces of previous work (or pentimenti) showing through. In rock art or cave art it would most often refer to trying to pick a recognizable image out of a mass of marks (scratches or lines). Some early recorders picked out whatever image they could decipher and often only recorded the lines of that image, ignoring all the other markings.

Paul Bahn explained the modern attitude toward such recording in his 1997 book Journey Through The Ice Age:

"Deciphering or copying images on a cave wall is rather like an excavation, except that the 'site' is not destroyed in the process; the pictures are 'artifacts' as well as art and, if superimposed, they even have a stratigraphy. Moreover, instead of selecting and completing animal figures from the mass of marks, like early archaeologists seeking, keeping and publishing only the belles pieces and ignoring the 'waste flakes', the aim for the last thirty years has been to copy everything. This helps to reduce psychological effects akin to identifying shapes in clouds or ink-blots: faced with a mass of digital flutings or engraved lines, the mind tends to find what it wants to find, in accordance with its preconceptions, and often detects figurative images which ae really not there. In addition, one needs to counteract the psychological effect whereby the eye is drawn to the deeper lines (although these may have been of secondary importance) and to lines in concave areas which are generally better preserved than those on convex areas which are more exposed to wear and rubbing.

To eliminate lines we do not understand is an insult to the artist, who did not put them there for nothing; where there are so many lines that it is difficult to 'isolate' anything, however, it is still necessary to 'pull out' any definite figures which exist hidden in the complex mass (this is also far less strain on the eyes), though one should still try to publish the mass, leaving the reader free to make a different choice. In his herculean twenty-five year study of the 1512 slabs from La Marche with their terrible confusion of engraved lines, Leon Pales isolated and published only those figures which his expert knowledge of human and animal anatomy revealed to his eye: but he estimated that only one line in 1000 has been deciphered on these stones. Unfortunately, there are very few scholars with similar skills in deciphering and reproducing Palaeolithic engravings." (Bahn 1997:55)

Horse image from plaque, Gonnersdorf,

Germany. From Bahn and Vertut, 1997.

Germany. From Bahn and Vertut, 1997.

Horse on plaque, Gonnersdorf,

Germany. From Bahn and

Vertut, 1997.

Germany. From Bahn and

Vertut, 1997.

One can search such a mass in the attempt to identify additional images as I have attempted to do. In my short examination of the detailed drawing I located a possible lion head in profile immediately behind the head of the horse. The lines are certainly there, but the question is was that actually intended to be a lion by the original creator, or is it merely a figment of my imagination. How many other figures can you find?

Horse and possible lion. Gonnersdorf,

Germany. From Bahn and Vertut, 1997.

Germany. From Bahn and Vertut, 1997.

REFERENCES:

Bahn, Paul G., and Jean Vertut,

1997 Journey Through the Ice Age, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Wikipedia

Labels:

cave art,

Germany,

Gonnersdorf,

paleolithic art,

palimpsest,

petroglyphs,

rock art

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)