Saturday, June 27, 2015

PAINTED HANDPRINTS AT THE MAYAN SITE OF SAN GERVASIO, COZUMEL, MEXICO:

Las Manitas, San Gervasio, Cozumel, Mexico.

Photograph Peter Faris, March 2015.

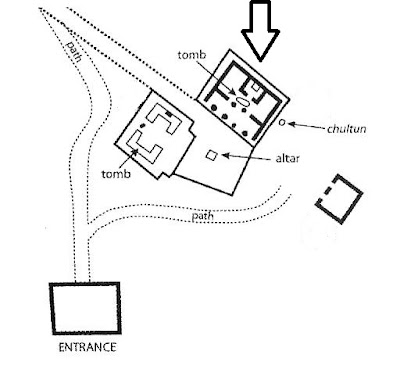

Las Manitas building group. Las Manitas marked by

the arrow. La Tumba to its lower left and Chichen

Nah to lower right. Hajovsky, p. 18.

On March 21, 2015, I visited the Mayan site of San Gervasio

on the island of Cozumel. There, in a structure known as Las Manitas (or the

Little Hands) are found walls decorated with red painted hand prints.

Las Manitas, San Gervasio, Cozumel, Mexico.

Photograph Peter Faris, March 2015.

Mayan settlement of the area began in the Early Classic Period (300 AD to 600 AD). (Hajovsky 2014:4) Las Manitas was constructed during the Terminal Classic (1000 - 1200 AD) and served as the residence of the halach uinik or Mayan ruler of Cozumel during that Terminal Classic Period. It has an outer room that was the residence and an inner sanctum that was a household shrine. (Wikipedia)

Hand prints from Las Manitas, San Gervasio,

Cozumel, Mexico. Photograph Peter Faris,

March 2015.

Floor plan of Las Manitas, San Gervasio,

Cozumel, Mexico. Hajovsky, p. 19.

"The structure was originally a one room dwelling, but later renovated by an elite family to include an outer room with an open, colonnaded front with plastered benches and a small inner-sanctum within the original interior room. The renovated building was purely Mayapan in style. In the 1970s, a colorful mural was still visible on the interior wall, but vandals have since chipped it away. During the 1970 excavations, a limestone sculpture of a sea-turtle was discovered in the rubble. It had probably been plastered upside-down into the ceiling, similar to others found at Mayapan. Today the turtle sculpture can be seen in the city museum. Under the floor of the interior room a tomb was also found, covered over with a huge cap-stone." (Hajovsky 2014:19)

Las Manitas is accompanied by a couple of other structures that appear to have been in relationship with it . In front of Las Manitas was a structure known as La Tumba (The Tomb). It was presented by my guide as a low pyramid, but is described in literature as an altar platform. It once supported a thatch-roofed building with a group of benches arranged around an altar. Underneath this platform was a vaulted-roofed tomb. Discovered in 1973, it is the only one of its kind discovered at San Gervasio to date. (Wikipedia)

Chichan Nah, San Gervasio, Cozumel, Mexico.

Photograph Peter Faris, March 2015.

To the east of La Manitas is found the Chichan Nah meaning small house. Also known as The Oratorio, it was constructed during the Post Classic Period (1200 - 1650 AD). This is believed to have been an oratorio, or chapel, used by the family of the halach uinik who lived in Las Manitas. It consist of a large outer room with a small inner sanctum containing an altar. (Wikipedia)

San Gervasio is believed to have been influential in the coastal ocean trade during the Mayan period. Although it does not contain the grand constructions of many mainland Mayan sites, its site on a relatively flat island covered with scrub forest means it did not have to soar over jungle canopy to look impressive to the subjects who supported it.

REFERENCES:

Hajovsky, Ric

2014 The Yellow Guide to The Mayan Ruins of San Gervasio, CZM,S. de R. L. de C. B., Cozumel, Q. Roo, Mexico

Wikipedia

Labels:

Cozumel,

Handprint,

Mayan,

Mexico,

pictograph,

rock art,

San Gervasio

Saturday, June 20, 2015

ROCK ART IN JAMAICA:

As I explain below, I wanted this to be a first-hand report of wonderful rock art that I hoped to see in Jamaica. It did not turn out that way. So this is now a review of publications by Lesley-Gail Atkinson (listed below in References) on the rock art of Jamaica.

Jamaian petroglyphs, pulseamerica.co.uk.

Years ago we took a cruise up the Alaskan Inside Passage on

a smaller ship. During that trip the Purser's office on the ship would go to

great lengths to help us make plans for our visits ashore with helpful information like the directions to Wrangell's Petroglyph Beach. They were friendly

and hospitable and went out of their way to help. Well, now we have just

completed a Western Caribbean cruise on the Serenade of the Seas/Royal

Caribbean, and it was a completely different experience.

I had confirmed that Jamaica (which was a scheduled stop)

has numerous rock art sites so I took my packet of information including

locations and even some pictures to the Shore Excursion desk to ask for help in

arranging visits to one or more sites. Now this is the desk of which the cruise

line's promotional material says "let

our helpful Shore Excursion staff customize your shore excursion for your most

memorable cruising experience."

The result was certainly memorable, but in a very negative way - they

refused to lift a finger or make a phone call to try to find directions, or a

guide, or even where I could look for postcards of the Jamaican rock art. In

other words they totally blew me off, essentially asking me to go away and quit

bothering them. There may actually still be cruises out there that will help

you try to do what you want to do, but Royal Caribbean is certainly not one of

them.

Leslie-Gail Atkinson, Rock Art of the Caribbean,

Fig. 4.2, p. 51, Birdmen pictographs at Mountain

River Cave, Photograph: Evelyn Thompson.

Most of the rock art on Jamaica was created by the early

Taino inhabitants of the island. Sources agree that caves were of great significance

to the Taino, serving as receptacles for the creation and nurturing of life and

as its entry point into the world. Some myths suggest that caves were the place

of origin for not only humans, but the sun and moon as well. Apparently caves

were also used by the Taino for burials and sanctuaries, and as places for

shrines where their Shaman could work to keep balance. Much of the rock art on

Jamaica is also found in caves. Most of this seems to consist of petroglyphs of

faces, although Mountain River cave reportedly has a large number of painted

images.

Leslie-Gail Atkinson, Jamaica: The Earliest Inhabitants,

Fig. 13.5, p. 181, Petroglyphs at Canoe Valley.

Two of the books I found are listed below in references. These writings by Leslie-Gail Atkinson were the most valuable. I have copied

illustrations from these so you can indeed see what is to be found. Also, a

little internet searching will give you an idea of the rock art to be found in

Jamaica. In particular, the book Rock Art

of the Caribbean provides a good overview and some helpful analysis. I got

my access to this through interlibrary loan, but if you are into building your

rock art library I would recommend this one. A number of papers by varying

authors in this volume cover a broad spectrum and offer a great beginning to understanding

the rock art of Jamaica, and elsewhere.

Atkinson, Lesley-Gail

2006 Jamaica: The Earliest Inhabitants: The Dynamics of

the Jamaican Taino, University of West Indies Press, Jamaica

Atkinson, Lesley-Gail

2009 Sacred

Landscapes: Imagery, Iconogaphy, and Ideology in Jamaican Rock Art, p. 41-57,

in Rock Art of the Caribbean, edited by Michele H. Hayward,

Lesley-Gail Atkinson, and Michael A.

Cinquino, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Labels:

Caribbean,

Jamaica,

petroglyphs,

pictographs,

rock art

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

BIRDS IN ROCK ART - THE ROADRUNNER:

Roadrunner petroglyph at 3-Rivers (with

footprint above him), New Mexico.

Photograph Jack and Esther Faris, 1988.

Roadrunner tracks, St. George, Utah.

Roadrunner petroglyph at 3-Rivers, New Mexico.

Photograph Jack and Esther Faris, 1988.

Roadrunner petroglyph at 3-Rivers, New Mexico.

Photograph Margaret Harris, 1987.

Once, at Galisteo Dike, south of Santa Fe, while focused upon the marvelous petroglyphs, I found myself attracted to movements out of the corner of my eye, way out at the edge of my peripheral vision. I looked that way a couple of times but saw nothing. Then, after another flicker attracted my attention, I sat down and just watched for a while. It was a warm morning and small lizards were crawling up on the patina-darkened cliffs to warm up. Then I saw what had attracted my attention - it was a roadrunner running up the cliff face to snatch a lizard before going back down. I watched for a number of minutes and saw a few repetitions of the performance before he (or she) quit and left. The roadrunner from 3 Rivers carved in a vertical pose on the rock reminds me of this. It even seems to carry a snake in its beak as it runs up the rock.

Roadrunner (Geococcyx californicus),

"The roadrunner, also known as a chaparral bird and a chaparral cock, is a fast-running ground cuckoo that has a long tail and a crest. It is found in the southwestern United States and Mexico, usually in the desert. Some have been clocked at 20 miles per hour (32 km/h)." (Wikipedia)

The genus Ceococcyx has just two (species), the greater roadrunner (G. californianus) inhabiting Mexico and the United States, and the lesser roadrunner (G. velox) inhabiting Mexico and Central America. (Wikipedia)

"The roadrunner is an opportunistic omnivore. Its diet normally consists of insects (such as grasshoppers, crickets, caterpillars, and beetles), small reptiles (such as lizards and snakes, including rattlesnakes), rodents and small mammals, spiders (including tarantulas, scorpions, centipedes, snails, small birds (and nestlings), eggs, and fruit, and seeds like those from prickly pear cactuses and sumacs." (Wikipedia)

"The roadrunner forages on the ground and, when hunting, usually runs after prey from under cover. It may leap to catch insects, and commonly batter(s) certain prey against the ground. Because of its quickness, the roadrunner is one of the few animals that preys upon rattlesnakes." (Wikipedia)

“Sityatki Polychrome, AD 1375-1625. Subject is the

hosh-boa, a bird called roadrunner or chaparral cock

which figured in an ancient Hopi courting ceremony.”

(Patterson 1992:95)

This last fact, that roadrunners actually are known to prey upon rattlesnakes, impressed the makers of mythology (and rock art as well) deeply. It impresses me deeply as well, having had a few encounters with rattlesnakes while out looking at rock art. Because of this, in much of the American southwest, the roadrunner is associated with warrior traits, and success in battle. This potential impact upon life and death has also led also to association with curing, and with security. (Tyler 1991:219-24) The roadrunner is definitely a remarkable and important character.

REFERENCES:

Patterson, Alex

1992 A Field Guide To Rock Art Symbols Of The Greater Southwest, Johnson Books, Boulder.

Tyler, Hamilton A.

1991 Pueblo Birds and Myths, Northland Publishing, Flagstaff.

Labels:

3-Rivers,

Birds,

footprints,

New Mexico,

petroglyph,

roadrunner,

rock art,

tracks

Sunday, June 7, 2015

INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE OLD SPANISH TRAIL, NORTH BRANCH – LOUIS ROBIDOUX:

On September 25, 2011, I posted a column entitled Antoine Robidoux, 13 November 1837 – An

Historic Inscription. In that posting I told the back story of a historic

inscription found along Westwater Creek, in eastern Utah. A lovely little

volume, Forgotten Pathfinders Along the

North Branch of the Old Spanish Trail, 1650-1850, self-published in Grand

Junction, Colorado, by Jack Nelson, contains a wealth of scholarship and

information about that trail and some of the historic inscriptions found carved

into the cliffs and boulders along it. I highly recommend this book for anyone

who is interested in historic inscriptions or the history of this part of the

west.

“In the late 1820's, Antoine and probably Louis set up a trading agency in Taos, for the centrality of its location and as a means of circumventing the customs office a hundred miles away in Santa Fe. After 1824, and for a period of about six years, the trade, though fluctuating, continued to increase. However, in the year 1830 a recession set in. The import tax steadily increased, while the price of trade goods dropped off. From the 1830's onward, the fur trade steadily declined, and with this decline, the Robidoux's shifted the focus of their activities and interests away from Santa Fe/Taos and more towards the Robidoux posts in the intermontaine corridor. After this date, he appears to have taken up a more permanent residence in Santa Fe, and to not have continued his sojourning in trapping and trading expeditions.

Louis appears in the account books of Manuel Alvarez buying supplies in 1829. In 1829, he also applied along with his brother Antoine for Mexican citizenship and was granted naturalization by the Mexican authorities a day later, on July 17th, 1829. He became Don Luis Robidoux. They are credited with this act in order to circumvent the customs taxes levied on foreign traders - marriage also gave them other distinct advantages in local society. http://www.lewismicropublishing.com/Publications/Robidoux/RobidouxLouis.htm.

“Louis probably served as the New Mexico agent for these posts, for they depended on New Mexico for supplies . . . On at least one occasion, in the spring of 1841, Louis Robidoux made the long journey to Fort Uintah . . . as he approached the Green River, he took the time to inscribe his name on a cliff in the Willow Creek drainage, some thirty-five miles south of [present-day] Ouray, Utah . . . The inscription reads:

Louis Robidoux

Louis Robidoux inscription, May 1841. From Nelson,

2003, Forgotten Pathfinders Along the North Branch

of the Old Spanish Trail, 1650-1850.

The Old Spanish Trail was blazed in part by Frays Dominguez

and Escalante in 1776 in their exploration to find a route to the Pacific

Ocean. They went north from the Taos area in Spanish New Mexico following

Indian trails until they hit the Colorado River near present day Grand Junction,

Colorado. Then they struck generally west to the Great Salt Lake before

returning back to New Mexico. Later, when mountain men and trappers were

combing the Rocky Mountains for beaver pelts in 1824 and 1825, and explorers

were searching for mineral wealth this became a favored exit from New Mexico

toward “Winty” territory, the Uintah area of Northwestern Colorado and

Northeastern Utah, and became known as the North Branch of the Old Spanish

Trail.

Map of the Trail up Westwater Canyon from Nelson 2003.

Antoine Robidoux inscription in the red star, Louis

Robidoux inscription location in the blue star.

As can be seen in the map the route follows Westwater Creek

in Northeastern Utah up through Hay Canyon and then crosses the divide before

coming down Willow Creek to join the Green River. This became known as the Robidoux Trail. The Antoine Robidoux

inscription alluded to above is to be found along Westwater Creek shortly before

it enters the Bookcliffs range (see the map (Nelson 2003:31).

The Robidoux brothers had opened a couple of Trading

Posts/Forts in central and northern Western Colorado, Fort Uncompahgre near the

present site of Delta, Colorado, and Fort Uintah up in the Brown’s Park country

of Northwestern Colorado. Antoine Robidoux’s brother Louis was quite involved

in the family business.

“In the late 1820's, Antoine and probably Louis set up a trading agency in Taos, for the centrality of its location and as a means of circumventing the customs office a hundred miles away in Santa Fe. After 1824, and for a period of about six years, the trade, though fluctuating, continued to increase. However, in the year 1830 a recession set in. The import tax steadily increased, while the price of trade goods dropped off. From the 1830's onward, the fur trade steadily declined, and with this decline, the Robidoux's shifted the focus of their activities and interests away from Santa Fe/Taos and more towards the Robidoux posts in the intermontaine corridor. After this date, he appears to have taken up a more permanent residence in Santa Fe, and to not have continued his sojourning in trapping and trading expeditions.

Louis appears in the account books of Manuel Alvarez buying supplies in 1829. In 1829, he also applied along with his brother Antoine for Mexican citizenship and was granted naturalization by the Mexican authorities a day later, on July 17th, 1829. He became Don Luis Robidoux. They are credited with this act in order to circumvent the customs taxes levied on foreign traders - marriage also gave them other distinct advantages in local society. http://www.lewismicropublishing.com/Publications/Robidoux/RobidouxLouis.htm.

“Louis probably served as the New Mexico agent for these posts, for they depended on New Mexico for supplies . . . On at least one occasion, in the spring of 1841, Louis Robidoux made the long journey to Fort Uintah . . . as he approached the Green River, he took the time to inscribe his name on a cliff in the Willow Creek drainage, some thirty-five miles south of [present-day] Ouray, Utah . . . The inscription reads:

Passo qui diade

Mayo de 1841

With the Robidoux

brothers’ inscriptions located as they were along the Westwater-Willow Creek

Trail, it would appear to be the one must used. - - - With the mouth of

Westwater Creek Canyon marking one of the few access routes over the Roan/Bookcliff

Range, the trappers undoubtedly used the trail and left other physical evidence

to show the way. The Louis Robidoux inscription marks a turnoff along the

Willow Creek Trail illustrating the path to the summit above Westwater Canyon.”

(Nelson 2003:51)

Louis moved to California in 1844, and settled in the area of

modern Riverside, California. (Wikipedia)

If you can find this book I highly recommend it not only for the information about historic inscriptions, but also about a fascinating period in the early exploration and settlement of the West. Thank you Jack!

If you can find this book I highly recommend it not only for the information about historic inscriptions, but also about a fascinating period in the early exploration and settlement of the West. Thank you Jack!

REFERENCE:

Nelson, Jack William

2003 Forgotten

Pathfinders Along the North Branch of the Old Spanish Trail, 1650-1850,

Copyright Jack William Nelson, Grand Junction, CO.

www.wikipedia.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)