Saturday, November 30, 2013

ARCHITECTURE IN ROCK ART – TIPIS – Part 1:

In their records left on the rocks by Native Americans of

their deeds and situations, we can look for clues to the environment that these

feats were performed in. One common feature of the environment in Great Plains

rock art is one or more residences, their tipis. In the tradition of Plains

Biographic Art much of the imagery in a composition is intended as information.

In this way a figure seen in relation to a group of tipis would represent a

specific person involved in some activity next to that tipi village.

Horseman in lower left, Anubis Cave, Cimarron

County, OK. Photo Peter Faris, 21 Sept. 1986.

My awareness of this came back in the 1980s on one of a

frequent number of trips down into southeastern Colorado. In the so-called

Anubis Cave in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, I saw a small equestrian figure on

horseback in front of the upside-down “V” of a tipi. It occurred to me at that

time that it placed a figure in a specific place, and thus at a specific time,

the time when he was there. In other words it was telling a story, a simple

story certainly, and one that did not provide me with much information, but a

story nevertheless. This is the basic premise of James Keyser in his statement

that the Biographic art of ledger books and painted robes can provide a lexicon

toward the interpretation of some rock art.

Las Animas County, CO. 1999.

Canyonlands, Las Animas County, CO. August, 1999.

In the Box Canyon Site in the Purgatoire river canyon in

southeastern Colorado a couple of panels illustrate combat in relation to

tipis. 5LA8464 was recorded in 1999 by a crew led by Jim Keyser and Mark

Mitchell. This is a large panel, faintly scratched into a large flat side of

the rock. This panel apparently records an attack upon a tipi village or family

encampment by a group of equestrian warriors on the right, whom I believe are

Pawnees by the details of their portrayal. The village or encampment being

attacked is represented by a tipi on the left side of the panel and would

probably have been Cheyenne or Arapahoe based upon the location. One defender

seen by the tipi has been struck by an arrow. A number of unridden horses

suggest that this combat bay have been in conjunction with a horse raid upon

this encampment.

Mark D. Mitchell, August 1999.

Another plains biographic rock art panel recorded by James

Keyser and Mark Mitchell is the Red Rock Ledge site in the Picketwire

Canyonlands, near the Box Canyon site. This smaller panel tells a story related

by Keyser in his subsequent published report. “The lightly-scratched petroglyphs at Red Rock Ledge compose a

Biographic scene showing a pedestrian bowman who has traveled from a tipi

village to engage and enemy represented by a crooked lance or coup stick.

Beginning at the right margin of the scene, and following the action to the

left, the composition consists of four major elements. At the far right is a

group of nine triangles with forked tops representing a camp of tipis. One

other incomplete figure probably represents a tenth tipi with one side no

longer visible. A series of seventeen more or less horizontal dashes and four

“C” shapes extends from the tipi camp toward the bowman. Based on comparisons

with other Biographic drawings in various media, the dashes represent human

footprints and the “C” shapes represent horse hoofprints. The third element,

the bowman, is a simply drawn, rectangular-body figure with a circle head. His

legs are shown with thighs, calves, and feet. The short diagonal lines that

extend outward from the front of each leg indicate fringed leggings. In his

right hand he carries a carefully drawn recurved bow that is shooting an arrow

with a large triangular point. The fourth element, located at the far left of

the scene, is a horizontally-oriented crook-neck coup stick, from which trail

four groups of paired streamers or feathers. Each group extends diagonally

downward to the left, and the four groups are spaced about equidistantly along

the shaft, with the last at the end of the crook.” (Keyser and Mitchell

2000:26-7)

In the well known horse pictograph/petroglyph from Picture

Canyon, in Baca County, Colorado, a number of very faint tipi shapes can be made out

with careful observation. Indeed, a group of four or five very faint

upside-down “V” shapes in the upper right corner of the photo represent a tipi

village, with at least two more at the top just left of center. These presumably represent the tipi village

that the horseman himself is associated with.

Numerous other examples of tipis portrayed in rock art can

be found in the literature. My point here is that in contrast to the common

assumption that “we can never know what rock art is saying” we can, in many

instances determine quite a bit about a rock art panel. I will show some other

examples and share some other thoughts in future columns.

REFERENCES

Keyser,

James D. and Mark D. Mitchell

2000 Red Rock Ledge: Plains

Biographic Rock Art in the Picketwire Canyonlands, Southeastern Colorado,

Southwestern Lore, Vol. 66, No. 2, Summer, 2000, p. 22-37.

Saturday, November 23, 2013

A LOST BUT UNIQUE REPORTED ROCK ART SITE - COYOTE’S PENIS:

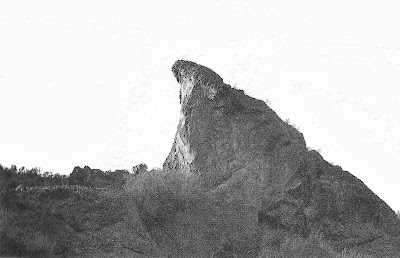

Coyote's Penis, Stein River Valley, British Columbia.

York, 1993, They Write Their Dreams on the Rocks

Forever, fig. 13, p. 8.

On occasion rock art would be located in a place that lends

meaning or power to the imagery because of features of the local topography.

Such a place is found in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia, Canada, at a feature known as Coyote’s Penis.

“Indians also

frequently painted pictures on rocks which were thought to be metamorphosis

beings (originally human or semi-human, semi-animal, or semi-God-like

character) concerning which, there were stories in their ancient mythological

tales or traditions. These rocks are generally boulders corresponding roughly

to human and animal forms or to parts of the body, etc., or to rocks worn into

peculiar or fantastic forms of various kinds, suiting in some way the story

that is told of them. By painting on them power in some degree, it was thought,

might be obtained from them or their spirits. . . (Teit 1918:3).” (York 1993:8)

“One of these sites is

found at Spence’s Bridge in the vicinity of Spaeks ha snikiap (Coyote’s Penis)

were the genitals of Coyote and his wife, as well as her woven cooking basket,

were turned to three rock formations by Xwekt’xwektl. Xwekt’xwektl had tried to transform them

totally to stone but due to the countervailing shamanic power of Coyote, the

transformer was able to succeed only with the Coyote’s penis, his wife’s vulva

and the basket kettle from which they had been picknicking (Teit 1898:44, n.

132; 1900:337).” (York 1993:8-9)

In this case the local First Nation’s population remembers

that there is a rock art panel near Coyote’s Penis but it has not been located

in contemporary searches. Perhaps some damage has destroyed it, or perhaps

vegetation is currently concealing the pictographs. One has to hope that it will be rediscovered and recorded as rock art from such a location carries possibly evocative meaning and content. At worst we can hope that it illustrates the myth recorded above, and thus would give us an opportunity for comparative analysis. In any case it does carry a very large curiosity factor.

REFERENCES:

Teit, J. A.

1898 Traditions

of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia, American Folklore

Society, Houghton Mifflin, New York.

York, Annie, Richard Daly, and Chris Arnett

1993 They

Write Their Dream on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings of the Stein River Valley

of British Columbia, Talonbooks, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Labels:

British Columbia,

Canada,

Coyote,

Coyote's Penis,

pictographs,

rock art,

Stein River

Saturday, November 16, 2013

HORSE DECORATION IN ROCK ART – FEATHERS:

Biographic panel from Joliet, Montana. Keyser and

Klassen, 2001, Plains Indian Rock Art, p. 237.

On any important occasion a Native American wanted to be as

memorable as possible. Part of the preparation for that was to dress oneself up

in finery, and that went for their horse as well. Not only for ceremonial occasions,

but often for combat, a warrior’s horse would have been painted with symbols

carrying spiritual protection, and announcing the warriors strength and

prowess. Another essential part of the decoration of any Native American’s

horse is eagle feathers.

Thomas Mails explained this as follows: “Golden eagle tail feathers were often tied to the mane and/or tail of

the war horse when the owner was about to go on a mounted war party. A common

Plains custom was that of tying up the horse’s tail when preparing for battle.

The Indians believed it sensible to get the long tails out of the horse’s way.

Sometimes the tail itself was simply tied in a knot. Other times it was folded

and bound with buckskin strips, or in trade days with red blanket cloth.

Feathers and fringes were often added to the ties for more spectacular effect.”

(Mails 1991:223)

Klassen, 2001, Plains Indian Rock Art, p. 237.

The rock art image from Keyser and Klassen Plains Indian

Rock Art (2001:237) located at Joliet, Montana, shows horses and riders in a battle.

The detail illustrates a feather decorated horse carrying two riders, the rear

rider turned and firing his rifle at an enemy. The image of a horse carrying

two riders is usually an illustration recording the heroic rescue of a downed

comrade in a battle. The horse that the two warriors are riding has an eagle

feather attached to its forelock and also appears to have three feathers

hanging from its tied-up tail. This horse was carefully decorated for war so I

assume that it represents the aggressors, the defenders presumably would have

been caught by surprise and not had enough time to make such careful preparations.

Horse petroglyph, Writing-on-stone Provincial Park,

Alberta, Canada. Three lines from the back of the

horse's head represent feathers, or possibly two

ears and one feather.

Alberta, Canada. Three lines from the back of the

horse's head represent feathers, or possibly two

ears and one feather.

“Siya’ka said that on

one occasion when he was hard pressed on the warpath, he dismounted, and,

standing in front of his horse, spoke to him saying: “We are in danger. Obey me

promptly that we may conquer. If you have to run for your life and mine, do

your best, and if we reach home, I will give you the best eagle feather I can

get – and you shall be painted with the best paint.”” (Horse Capture and

Her Many Horses 2006:41)

Horse images with decorative feathers attached are found in

many media utilized by Native American artists. Some examples are shown and

listed below.

Bone quirt handle. George Horse Capture and Emil Her

Many Horses, 2006, A Song For The Horse Nation,

Horses in Native American Cultures, p. 38.

Bone quirt handle showing a feather tied to the tail of the horse – “1870s, By

identifying stylistic motifs, scholars can often determine which groups created

the drawings, and occasionally, a match can be found by comparing figures in

rock art to those items made by contemporary tribes, confirming that some

ancient art styles reach across the centuries. A wedge-shaped

anthropomorphic figure carved into a stone wall in southern Alberta, Canada, is

similar to the one incised into the handle of this quirt, collected in the

early twentieth century.” (Horse Capture and Her Many Horses 2006:38)

Portrait of High Wolf. George Horse Capture and Emil Her

Many Horses, 2006, A Song For The Horse Nation, Horses

in Native American Cultures, p. 40.

Ledger painting, horse with feathers both on his tail and forelock – “Yellow

Nose (Ute raised as Cheyenne), Portrait of High Wolf, circa 1880. This drawing

shows high wolf counting coup with a riding quirt against a Nez Perce. The

imitation scalp under the horses chin indicates the accomplishments of both

horse and rider.” (Horse Capture and Her Many Horses 2006:40)

Many Horses, 2006, A Song For The Horse Nation,

Horses in Native American Cultures, p. 70.

Shield cover, horse with feathers tied to his tail - “Cheyenne

River Sioux painted hide shield cover, circa 1880s – This shield cover records

a battle scene between the Lakota and some of their enemies, possibly Crow or

Pawnee, who are recognized by the topknot hairstyle that was popular with both

tribes. The hero/owner of this shield, wearing a split horn war bonnet, is at

the center, moving left.” (Horse Capture and Her Many Horses 2006:70)

and Emil Her Many Horses, 2006, A Song For The Horse Nation,

Horses in Native American Cultures, p. 87.

Ledger portrait, the horse has a feather fan tied to his tail – “Red

Dog (Lakota), Portrait of Few Tails, circa 1884. Fully decked out in warrior

society accoutrements, Few Tails appears to be dressed for battle. Most

portraits, like this one, incorporate stylized faces. Because each Plains warrior’s

shield was decorated differently, individuals or tribes were identified in

artwork by their shield designs and clothing styles.” (Horse Capture and

Her Many Horses 2006:87)

As Jim Keyser has demonstrated in his many analytic rock art publications, much can be learned from careful attention to the details in rock art, and by comparison with other art forms which display the same sort of imagery. In the case of horses decorated with feathers it can represent a warrior prepared for war, or for a ceremonial occasion.

REFERENCES:

Afton, Jean, David Fridtjof Halaas, and Andrew E. Masich

1997 Cheyenne

Dog Soldiers: A Ledgerbook History of Coups and Combat, Colorado Historical

Society and University Press of Colorado, Denver.

Horse Capture, George P. and Emil Her Many Horses

2006 A Song

For The Horse Nation, Horses in Native American Cultures, National Museum

of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., and Fulcrum

Press, Golden, CO.

Keyser, James D.

2012 “My Name Was Made High:” A Crow War Record

at 48HO9, The Wyoming Archaeologist,

Vo. 55, Spring 2011 (pub. Oct. 2012).

Keyser, James D. and Michael A. Klassen,

2001 Plains Indian Rock Art, University of

Washington Press, Seattle.

Mails, Thomas E.

1991 Mystic Warriors of the Plains, Barnes

and Noble Books, New York.

Labels:

feathers,

Horse,

horse decoration,

ledger art,

petroglyph,

rock art,

shield

Saturday, November 9, 2013

DEVIL’S TOWER, WYOMING:

Bear's Lodge Butte (Devil's Tower), Wyoming.

Photograph: Peter Faris, June 2013.

High on every list of sites that are

sacred to Native Americans is Bear Lodge Butte, listed on our maps and in our

records as Devil’s Tower. I can remember being fascinated with this pretty much

all of my life after seeing a picture of it in a Little Golden Guide to Geology

as a child.

Bear's Lodge Butte (Devil's Tower), Wyoming.

Photograph: Peter Faris, June 2013

In his book Where Lightning Strikes: The Lives

of American Indian Sacred Places, Peter Nabokov gave a description of the

beliefs and mythology that are attached to this location by Native Americans. “Best

known of the Black Hills outliers was what Indians called Bear Lodge Butte, but

which whites in offensive contrast to its heroic role in Indian mythology, came

to name “Devil’s Tower.” Remembered by most Americans, this volcanic upthrust,

located to the north of the Hills that jutted into the sky like a great horn

with its tip lopped off, was the Mother Ship’s landing pad in director Steven

Spielberg’s 1977 science fiction classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But

to the Kiowa tribe the 867-foot promontory was revered as T’sou’a’e, or “Aloft

on a Rock.” Here was the embarkation point for that early period in Kiowa

Indian history that the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist N. Scott Momaday called

“the setting out.” From these high plains their ancestors migrated south, to

ultimately reach the area of Rainy Mountain in western Oklahoma, where their

reservation is found today.

Like a number of Plains Indian tribes,

the Kiowa never forgot the Tower’s place in their mythology. They told of the

seven sisters and a brother who were playing together. Transformed into a

monster bear, the brother attacked his sisters, who ran for their lives. When

they reached a giant tree stump it told them “climb up on me.” Once they were

on top the stump began to grow, leaving the bear pawing at them and raking its

sides with his claws – those vertical grooves remain to this day. On the summit

the girls were finally safe, but the Kiowa say the sisters then ascended into

the sky, to become the constellation we know as the Big Dipper (other tribal

versions say the Pleiades).” (Nabokov 2006:215-16)

We finally undertook the trip there in

June 2013. A long day’s drive got us to Sundance, Wyoming, which serves as the

gateway to the Devil’s Tower National Monument. In Sundance we had a nice motel room at a reasonable price, and ate fine meals in a couple of good restaurants. The next day we drove out to

the tower itself. It was every bit as impressive as I had hoped. We hiked

around the spire and saw probably a couple of dozen rock climbers working their

way up various routes. I could certainly get a small sense of the unease that

Native American peoples feel to a greater extent seeing these people climbing

up this sacred rock.

Offerings at Bear's Lodge Butte (Devil's Tower),

Wyoming. Photograph: Peter Faris, June 2013.

While walking around the vicinity of

the rock many small offerings could be seen in the trees in various locations around

the tower reinforcing its spiritual nature for some people. I am pleased to be able to report that there does not seem to be any meddling with these offerings, such as collecting or removing them.

As we might imagine for a site with such spiritual significance there is rock art in the area although the park personnel greet such inquiries with an assumed air of ignorance. In her interesting book Storied Stone: Indian Rock Art in the Black Hills Country, Linea Sundstrom has illustrated petroglyphs at a site designated 48CK1544, which is located within view of the tower.

Left side of main panel, Site 48CK1544,

Sundstrom, Fig 12.4, p. 146.

Right side of main panel, 48CK1544,

Sundstrom, Fig. 12.4, p.147

Incised face and design, 48CK1544,

Sundstrom, Fig. 12.6, p.147.

Sundstrom wrote about the rock art near Devil's Tower "petroglyphs located upon a ridge within distant view of Devil's Tower reflect a link between landscape and rock art. Although they are part of the incised rock art tradition, these petroglyphs are unlike others in the area. Some of the rock art represents thunder beings - eagle- or hawklike creatures with outspread wings (fig. 12.4). One petroglyph shows a creature with some human and some thunderbird characteristics. Perhaps these record the trance of some vision seeker."

For more about the rock art near Devil's Tower and, indeed, for rock art throughout the Black Hills region read Linea Sundstrom's writings. And, for a great trip to a beautiful area, and a moving experience, I highly recommend a visit to Bear's Lodge Butte/Devil's Tower.

REFERENCE:

Nabokov, Peter

2006 Where Lightning Strikes: The Lives

of American Indian Sacred

Places, Peter Nabokov, Viking Press, New York.

Sundstrom,

Linea

2004 Storied Stone: Indian Rock Art of the Black Hills Country,

University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

2004 Storied Stone: Indian Rock Art of the Black Hills Country,

University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Labels:

Bear Lodge Butte,

Devil's Tower,

Linea Sundstrom,

petroglyphs,

rock art,

Sundance,

Wyoming

Sunday, November 3, 2013

HORSE DECORATION IN ROCK ART – PAINT:

Warriors of the Plains horse tribes painted their horses for

special occasions. These painted markings and symbols were not so much an identifier

in the nature of the Angle horse brand as they were an enhancement, visual or

spiritual, of the horse’s and the rider’s presence. Some of the symbols represented

specific accomplishments and so could be read like a biography of the warrior.

Other symbols conferred spiritual powers and abilities that had been shown to

the warrior on a vision quest. Some examples of painted horses can be seen in

rock art and other Native American art forms, and some of these messages can

still be read in the painted markings.

Symbols from painted horses, Thomas E. Mails,

Mystic Warriors of the Plains, 1991, p.220.

Thomas Mails illustrated a number of commonly seen marks in

his book Mystic Warriors of the Plains (Mails 1991:220) and examples (including

variations) of some of these symbols can be seen in examples of Native American

art. “Painted exploit symbols used on

horses. a, war party leader. b, enemy killed in hand combat. c, owner fought

from behind breastworks. d, hail. e, coup marks. f, horse raids or number of

horses stolen. g, mourning marks. h, medicine symbol.” (Mails 1972: 220)

Picture Canyon, Baca County. Photograph: Peter Faris.

Close-up of symbol on the horse from Picture

Canyon, Baca County, Colorado.

In Picture Canyon, Baca County, Colorado, a horse figure

that is faintly drawn in black and also lightly incised into the cliff face has

markings carved into his front shoulder that might represent a variation of

Mail’s marks for coup counts. An extremely faded rider can be made out and the

shapes of tipis in the background are now almost invisible.

Coup count symbols can be seen on the horse illustrated in

one of the plates in the Dog Soldier

Ledger (p. 91, p. 189) in which an unidentified warrior has dismounted to

count coup with a strike of his bow on a wounded soldier.

An incised panel from Joliet, Montana, is illustrated in

James Keyser’s and Michael Klassen’s 2001 book Plains Indian Rock Art (p. 237). The large horse in the center of

the illustration carries an “H” on his hip which might represent an Anglo

brand, but the horse also shows a open-bottom rounded symbol on his front

shoulder which is quite possibly Mail’s symbol for horse raids and/or horses

stolen, a could possibly actually refer to the capture of the horse illustrated

by its rider.

White Bird lancing a soldier, a circle is painted

on the hip of his horse. Dog Soldier Ledger,

plate 100, p. 203.

Another illustration from the Dog Soldier Ledger (p. 100, p. 203) shows White Bird lancing a white man. White Bird’s horse is painted with a circle identified by Mails as signifying fighting from behind breastworks or from some sort of defensive position. Additional illustrations of White Bird in the same publication show the same symbol on his horse.

“A warrior often

painted his favorite war horse with the same pattern and colors he used for his

own face and body. And when he was preparing for ceremonial events or for

journeys into enemy territory, he painted his horse at the same time as he

painted himself. – The main thing to bear in mind is that the painted horse

always carried a message about his owner, hence sometimes the quality of the

horse bearing the marks – although the painted horse might not always be the

one the owner had ridden on the raids described.” (Mails 1991:219)

The value and importance of the horse painting is

illustrated by George P. Horse Capture and Emil Her Many Horses in their 2006

book “Song for the Horse Nation”. “Siya’ka

said that on one occasion when he was hard pressed on the warpath, he

dismounted, and, standing in front of his horse, spoke to him saying: “We are

in danger. Obey me promptly that we may conquer. If you have to run for your

life and mine, do your best, and if we reach home, I will give you the best

eagle feather I can get – and you shall be painted with the best paint.””

(Horse Capture and Her Many Horses 2006:41) “The best paint” presumably is paint made with

the rarest, or hardest to acquire, pigments, the value being due to the effort

or expense of acquisition.

A range of motives and reasons led to painting of their horses by Native American Plains warriors, and many of these motives and reasons were of such importance that the same symbols were occasionally portrayed on rock art of horses. Indeed, many of these symbols can often be found independantly painted or pecked into the rock as well, but that is a subject for a later posting.

A range of motives and reasons led to painting of their horses by Native American Plains warriors, and many of these motives and reasons were of such importance that the same symbols were occasionally portrayed on rock art of horses. Indeed, many of these symbols can often be found independantly painted or pecked into the rock as well, but that is a subject for a later posting.

REFERENCES:

Afton, Jean, David Fridtjof Halaas, and Andrew E. Masich

1997 Cheyenne

Dog Soldiers: A Ledgerbook History of Coups and Combat, Colorado Historical

Society and University Press of Colorado, Denver.

Horse Capture, George P., and Emil Her Many Horses

2006 A Song

For the Horse Nation: Horses in Native American Cultures, National Museum

of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., and Fulcrum

Press, Golden, Colorado.

Keyser, James D.

and Michael A. Klassen

2001 Plains

Indian Rock Art, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Mails, Thomas E.

1991 Mystic Warriors of the Plains, Barnes

and Noble Books, New York

Labels:

Biographic Style,

horse decoration,

horses,

ledger art,

painted horses,

petroglyphs,

rock art,

symbol

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)