Mayan glyph for Venus, Patterson, A Field Guide To Rock

Art Symbols Of The Greater Southwest 1997, p. 76.

The symbol of the outlined cross is commonly identified as a representation of Venus. In mesoamerica it symbolized Quetzalcoatl in his aspect of the morning star and indeed the Mayan glyph for the planet Venus includes an outlined cross (Patterson 1996:76). In light of known connections between the American southwest and mesoamerica we might well suspect that the influence of this symbol was shared between prehistoric peoples of both regions.

Winter solstice sunset, Goodman Canyon.

From Bostwick, Landscapes of the Spirits, 2002.

A study of Hohokam rock art in South Mountain Park at Tucson, Arizona, has recorded some

fascinating connections of rock art and mythology of those people in this area. Archaeologist

Todd Bostwick wrote about this in Landscape of the Spirits, Hohokam Rock Art at South

Mountain Park, photographs by Peter Krocek, University of Arizona Press, Tucson (2002).

Bostwick recorded a number of solstice sunrise and sunset alignments from locations that also were marked by rock art. From one location that they named the Morning Star site they photographed a summer solstice sunrise from a boulder upon which a petroglyph of a snake is crawling upward. In another location that they dubbed the Gila Vista site they photographed a winter solstice sunset. Remarkably, the viewing point at this site is a pointed boulder with a petroglyph of a thick-bodied lizard, possibly a horned toad, facing downward pecked on the face of it. There was one example however of a Winter solstice sunset photographed behind a boulder with an outlined cross inscribed on it. Sited in a location in Goodman Canyon, it leads one to speculate that what was being recorded by this alignment might have not been the sunset, but the setting of Venus as the morning or evening star.

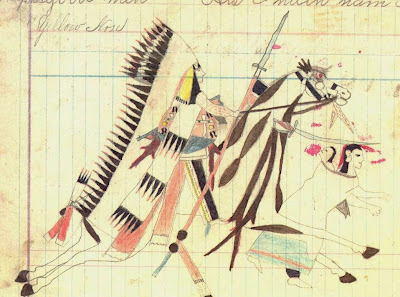

Johnson Canyon, Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, CO. Southwestern

Lore, Vol. 59, No.2, Summer 1993, p. 23.

Another example is seen in the photo taken by the author in Johnson Canyon, on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation in southwest Colorado. In this instance the outlined cross of Venus accompanies a concentric circle sun symbol and a pair of anthropomorphs (Faris 1993: 23).

References:

Bostwick, Todd W.

2002 Landscape of the Spirits, Hohokam Rock Art at South Mountain Park, photographs

by Peter Krocek, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Faris, Peter

1993 A Meteorological Model for the Concentric Circle Sun Symbol of the American Southwest, pages 23 – 27, Southwestern Lore, Vol. 59, No.2.

Patterson, Alex

1992 A Field Guide To Rock Art Symbols Of The Greater Southwest, Johnson Books, Boulder